Editor’s Note: We welcome and publish this article by Mphutlane wa Bofelo, a veteran South African activist and thinker, as part of the needed dialogue about how to overcome the separation between philosophy and organization and the separation between theory and practice. The article addresses these problems through a detailed discussion of the relation between the South African Communist Party and the ruling African National Congress. In this and all other cases, the articles we publish represent the positions of their authors. Only those articles signed or issued by Marxist-Humanist Initiative represent the positions of our organization itself.

Mphutlane wa Bofelo is a South African cultural worker, learning and development facilitator, and political theorist who focuses on political development, worker education, governance and political transformation, and strategy and leadership. He has lectured on Political and Social Development and Labour Economics at the Durban-based Workers College of South Africa, and is currently the Training Coordinator in the Member-Affairs Section of the Public Servants Association of South Africa (PSA).

Mphutlane wa Bofelo

THE DILEMMAS OF NON-RULING SOCIALIST/COMMUNIST PARTIES WITHIN ALLIANCE/COALITION POLITICS—THE CASE OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN COMMUNIST PARTY

by Mphutlane wa Bofelo

Although there are a few parties professing Marxist-Leninism that oppose cooperation with or participation in coalitions and united fronts that include non-communist, even anti-communist elements, the majority of the parties support alliance, coalition, and united-front politics, as informed by the balance of forces. The supporters of coalitions take their cue from Dimitrov’s 1935 report to the 7th Congress of the COMMINTERN, which cautions against self-isolating sectarianism and calls for the building of peoples’ fronts against fascism and war. In the report, Dimitrov implores communists to work hard to coordinate tactics with other parties and organizations, including non-working-class parties (Schepers, 2020).

The history of communism is replete with examples of ruling communist parties in a coalition set-up. The new government that emerged out of the 1917 October Revolution in Russia was initially a coalition between the Bolsheviks and the Left Social Revolutionaries. The coalition ended in 1918 after the Left Socialist Revolutionaries assassinated the German ambassador, Count Wilhem von Mirbach-Harff, with the aim of renewing the shooting between Germany and Russia, thereby undermining the Brest-Litovsk peace-treaty and the strenuous efforts of the government under the leadership of Vladmir Lenin to put an end to the war (Schepers, 2020). However, the short-lived coalition set a precedent for communists to be in a coalition government with non-communists or to launch the struggle for seizure of political power through political cooperation with others.

In Cuba, the alliance between the Twenty Sixth July Movement, the Peoples Socialist Party (Partido Socialista Popular–PSP) and the student-based organization, Revolutionary Directorate (Directorio Revolutionario) brought the defeat of the Batista dictatorship. As much of the most socialist-inclined elements of the three organisations merged to establish the Communist Party of Cuba in 1965, the interaction between the three was complex. The process of working together as the new government to formulate policy was not always harmonious (Cushion, 2016; Schepers, 2020).

In Vietnam, the Communist Party under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh did its political and military work, which led to its victory against French, Japanese and American imperialism, with and through a broad front organization, the League for Independence of Vietnam (Viet Minh). This front consisted of communists and non-communists. Currently, the Vietnamese Communist Party governs in a broad coalition with the Fatherland Front and many other groups and organizations (Schepers, 2020). Even the communist parties that came into power in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and erstwhile East Germany (i.e., the German Democratic Republic) usually ruled in coalition with other left and center-left parties.

Drawing on this history, communist parties often use coalition-building and united-front politics to contest power and participate in government. Schepers (2020) asserts that communist parties enter coalitions, united fronts, or informal cooperative agreements to defend and represent the interests of the working-class and because of the belief that absenteeism would be a harmful purist theatre that leaves the workers and other vulnerable groups unrepresented and isolated.

In a 1982 study, Sidney Tarrow examined why, despite their meagre results at the polls, nine non-ruling communist parties in Europe continued to have sporadic participation in multi-party coalitions in government. He said that communist parties enter governments during perceived socioeconomic or political crises, or as a left-wing of a multi-party coalition in which the communist parties occupy a central position within the left coalition, while the centrist parties and republicans hold centre stage within the opposite conservative pole (Tarrow, 1982). Tarrow delineated the motivations for the participation of communist parties in such coalition governments or alliance politics as the perception of the communist parties that a crisis prevails and a fear of being absent during a critical period.

This view correlates with the observation of Schepers (2020) that a significant consideration for communist participation in coalition politics and coalition governments is that the vacuum they create would be filled by others. In other words, they fear that if communist parties and other left-wing forces do not reach out to sectors of the working-class and the population, then others, including right-wing populist and fascists, will do so (Schepers, 2020). Hence, Tarrow (1982) concludes that the need not to be isolated or marginalised within the political arena causes communist parties to support moderate policies, actively or passively, and to form alliances with normally anti-communist elements. This implies the belief that communist parties have the theoretical and practical acumen that can take the country out of a crisis, but that they either lack the courage, will and capacity to take the reins of political power or believe that the balance of forces doesn’t allow them to do so on their own.

The observations of Tarrow correlate with the proposition that, although the political cooperation between the African National Congress (ANC), Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the South African National Civics Organization (SANCO) has historical and ideological roots, their alliance in the post-1990 dispensation is a product of the coincidence of political interests (O’Malley, 2000). On the eve of the first national democratic elections in 1994, the ANC sought organizational skills, material support, membership and votes or electoral support from COSATU, SACP and SANCO. On the other hand, COSATU and SANCO needed a political organization that can win elections, hold political power, and advance a progressive agenda and safeguards for labour and civil-society interests in parliament. At the same time, the ANC had the need to enlist seasoned strategists, tacticians, organizers and campaigners from its alliance partners. Its electoral prospects depended greatly on the numbers that the constituencies of its alliance partners added to its membership and support base.

Furthermore, the reputable political militancy, organizational skills and ideological insights of the SACP gave it a powerful base within the constituency of both the ANC and COSATU. However, the SACP did not have enough popular support to be a political force on its own in parliamentary politics where numbers are important. Therefore, the SACP had to remain a partner of the ANC to try to get the ANC to incorporate its social objectives and agendas (O’Malley, 2000).

The SACP did foresee that, once the ANC was in political office, it would be tall order to mediate and harmonise the latter’s multi-class and centrist politics with the former’s professed working-class and leftist politics. In lieu of this eventuality, the SACP opted to use, as its key tactical device, the notion of its members and those of COSATU and SANCO swelling the ranks of the ANC, with the aim of populating ANC spaces and platforms with communist ideas and the party line.

The other tactical devices it utilised were: (1) intensifying efforts to influence the political perspective of COSATU unions and education and research labour service organizations, such as Ditsela and the Workers College of South Africa; (2) deploying some of its seasoned cadres to take up leadership and influential positions within COSATU and the labour service organizations; (3) lobbying and campaigning for the leading activists of SACP, Cosatu and SANCO to have fair representation in the parliamentary and ministerial list of the ANC; and (4) pushing for extensive consultation and engagement of alliance partners on significant policy and programmatic issues relating to both the ANC and the government.

The unintended and negative consequences of this strategy was a brain drain within the leftist component of the alliance (i.e., COSATU, SACP and SANCO) as the result of an exodus of its seasoned leaders and activists to government. This also created the problematic situation in which these members found themselves bound both by the oath of office and by ANC processes.

This compelled them to implement policies and programmes of the ANC, even when they were at odds with their own personal values and the principles of COSATU, SACP and SANCO. The other challenge that this arrangement created was the political careerism tendency whereby individuals perceive and use their positions of leadership and influence within COSATU, SACP and SANCO as a social currency and stepping ladder to access deployment into government or business with government. This made the allies of the ANC prone to being enmeshed in internal factional divisions of the ANC, as they had to be in the “good books” of whichever faction of the ANC became victorious in the contest for control of the government. This is reflected in how the SACP and COSATU threatened to pull out of the alliance in 2006, but backtracked after former President Jacob Zuma emerged victorious at the Polokwane conference, and religiously defended Jacob Zuma throughout the so-called nine wasted years until the dying hours of the second term of Zuma in office.

As for the ANC, its enlistment of leading and experienced activists of its alliance partners in its election list—and subsequently the legislature and the executive, and various provincial and local government structures—meant that it hit three birds with one stone: it (1) acquired the votes of constituencies of its alliance partners; (2) acquired the political and technical skills of the leadership and activists of these alliance partners; and (3) put them in a situation in which they are obliged to implement, and co-opt them to, neoliberal-capitalist policies and programmes. The ANC has realised that the fact that it is the de facto leader of the alliance and that leaders and activists of its partners are administrative personnel deployed in government or the business sector on its ticket, reduces the capacity of the latter to deviate from ANC policies or to shape its social policy and political economy trajectory.

As soon as serious differences on policy occurred, the ANC flexed its muscles and openly told the alliance partners that, if they want to pursue a socialist, communist, or social-democratic agenda, they must do so on their own and not expect the ANC to do so on their behalf. A telling example is when the late President Mandela read the riot act to COSATU at its own congress, telling them that they can’t dictate ANC policies. Mandela rebuffed COSATU’s opposition to GEAR with a resonant declaration that GEAR is and shall remain ANC policy.[1] Another example is the statement of the former President Thabo Mbeki when he ejected an SACP leading activist, Nozizwe Madlala-Routledge, from his executive for daring to challenge government policies. Mbeki remarked that, as a member of the executive, Madlala-Routledge was bound to the policies and programmes of the ruling party and that she cannot serve in the executive whilst criticising government policies.

As the tensions of being in alliance with the ruling party and serving in the legislature and executive at its bidding increased, the SACP had to deal with the problem of its relationship with state power and the ruling power. In a 2006 discussion document on state power (Bua Komanisi, 2006), the SACP reaffirmed its position that the chief instrument of achieving the immediate goal of national democratic revolution (NDR) is a multi-class mass movement or liberation front, and that the ANC is such an instrument. The Party further stated that its loyal participation in the multi-class mass movement or liberation front is to represent the working-class as a class that it (SACP) claims to be the vanguard of. It further reiterated the idea that the goal of swelling the ranks of the labour movement and the multi-class mass movement is not to capture either the labour movement or the liberation movement and turn them into its wing, but to illustrate that its members are the most ideologically advanced section of the liberation front (Bua Komanisi. 2006).

While asserting that the dominant force in the alliance should be the working-class, the SACP reaffirmed its view that the ANC is the leader of the alliance. The whole question of how to assert the dominance of the working-class, and advance the renewal and revitalization of the socialist project chiefly through government policies and programmes dictated by a multi-class mass movement rather than by the communist party, has provided a theoretical and practical quandary for the SACP.

In addition to asserting that socialism is not realizable in the immediate future (Bua Komanisi, 2006) and resorting to transform itself from a cadre-based to a mass-based political party, the SACP resolved to assume responsibility for what it refers to as partial power and possibilities at its disposal, to make its own contribution to the NDR, and to build momentum towards, capacity for and even elements of socialism in the present (Bua Komanisi, 2006). According to the SACP, this entails doing its best to roll back the empire of the so-called free market and build confidence in the masses to take on the soulless secular religion of neoliberalism (Bua, Komanisi, 2006).

The reality, however, is that the SACP does not have partial political power. It does not participate in the legislature and the executive or any formal structures and processes of government and the state on its own, based on its own policies and programmes. It has access to political office and participation in government structures and processes as well as platforms for discussing the social policy and political economy of the country at the behest of the ANC. It is ANC structures and processes that prevail over the social policy and political economy path of the government led by the ANC. Thus far, other than episodic shadowboxing with the ANC on policy issues and theatrical threats to delink from the alliance, there is not much that the SACP has up its sleeve to make its social and political agenda take root within the ANC and government spaces. In theory, the ANC’s big tent provides an open pulpit or contested terrain but, practically, the centrist denomination is the ecumenical council of the ANC’s broad-church.

Quite a significant number of the top brass of the SACP at the national, provincial, and local levels are entrapped in or are eyeing full-time careers in politics (as members of Parliament, ministers, members of provincial Executive Councils, mayors, councillors, members of mayoral committees, etc.), courtesy of the ANC. This opens up possibilities for them to be ensnared in the ANC’s patronage system and therefore unable to significantly raise a socialist/communist voice within the ANC and the government it leads. This arrangement arrests possibilities for SACP, COSATU and SANCO activists within government to always act in conformity with the professed social and political agendas of their organizations. It is noteworthy that the three persons at the centre of the campaign to freeze the wages of workers in the public service and deny them an increase, in the name of reducing the so-called bloated public service wage-bill, are former shop stewards, trade union leaders and erstwhile firebrand fighters against capitalist super-exploitation of labour: President Cyril Ramaphosa and Ministers Enoch Gondogwana and Thulasi Nxesi; the latter is the current deputy national chairperson of the SACP.

The phenomenon of former COSATU and SACP leaders religiously implementing neoliberal capitalist and anti-worker policies and programmes once in political office is not new. Among other instances, this is illustrated by how SACP stalwart Pravin Gordhan became a monopoly-capital-compliant finance minister, from 2009 until 2014 and from 2015 to 2017, and is still pursuing free-market oriented agendas in his current position. The very first pronouncement of former General Secretary and current national chairperson of the Party, Dr Blade Nzimande, upon becoming the Minister of Higher Education, was that free tertiary university is not possible in the nearest possible future. Nzimande went further to propose that even when free education is possible, it will be a targeted provision, directed solely towards the poor and underprivileged, not blanket free education for all. This position is completely opposite to the universal provisioning of free and quality education for all, that sincere communists, socialists and even social democrats advocate.

It is not unusual to see SACP people chanting the mantra that it is cold outside of the ANC and that only the ANC can facilitate and drive political and social revolution in South Africa. This accounts for the unfolding drama wherein talk of reconfiguring the alliance, or even open threats to delink from the alliance, prevail prior to national general elections and dissipate as soon as the list of Members of Parliament and the ministers have been announced.

With its rich political history and its tremendous political skills and ideological currency, including its influence on COSATU and SANCO, the SACP has a lot of possibilities to innovatively reposition itself on the political stage. It could opt to contest elections on its own with the support of radical elements within COSATU and SANCO, without ending its political collaboration with the ANC on common issues, and even while entering into a post-election pact with the ANC. The chances of the SACP tilting the ANC more to the left would be much higher if the two parties were in a political cooperation in which the SACP contested elections on its own. Under such circumstances, it would be easier for the SACP to place conditionalities on its political cooperation with the ANC than it is when it participates in government at the invitation of the ANC. Furthermore, if the SACP contests elections on its own, but retains its political cooperation with the ANC in the form of an electoral pact or as part of a coalition, it will not necessarily fall with the ANC when the majority of South Africans ultimately opt to ditch the ANC at the polls, nor will it be at the receiving end of the fury of the masses, should public discontent against the ruling party reach high voltage.

The other alternative is for the SACP to take alliance and coalition-building politics beyond the mass democratic movement and explore collaborations or unity-in-action with the progressive and radical elements of the broader civic, social, and labour movements, and the various green, socialist, and feminist organizations outside of the congress movement. This should include active support of and participation in community and labour struggles. The SACP could play a pivotal role in uniting and mobilising COSATU, the South African Federation of Trade Unions (SAFTU), the National Council of Trade Unions (NACTU), etc., and in building a popular front that includes political and social movements such as the Bolsheviks Party of South Africa (BSPA), the Socialist Revolutionary Workers Party (SRWP), the Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front (ZACF), the Workers International Vanguard Party Land Party, the Workers and Socialist Party (WASP), the Socialist Party of Azania (SOPA), Abahlali BaseMjondolo, Equal Education, the Poor People’s Alliance, the South African Unemployed Peoples Movement, Sikhula Sonke, Treatment Action Campaign, and the Socialist Group.

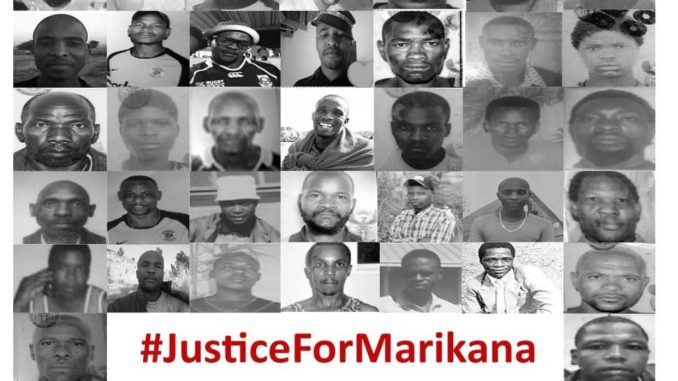

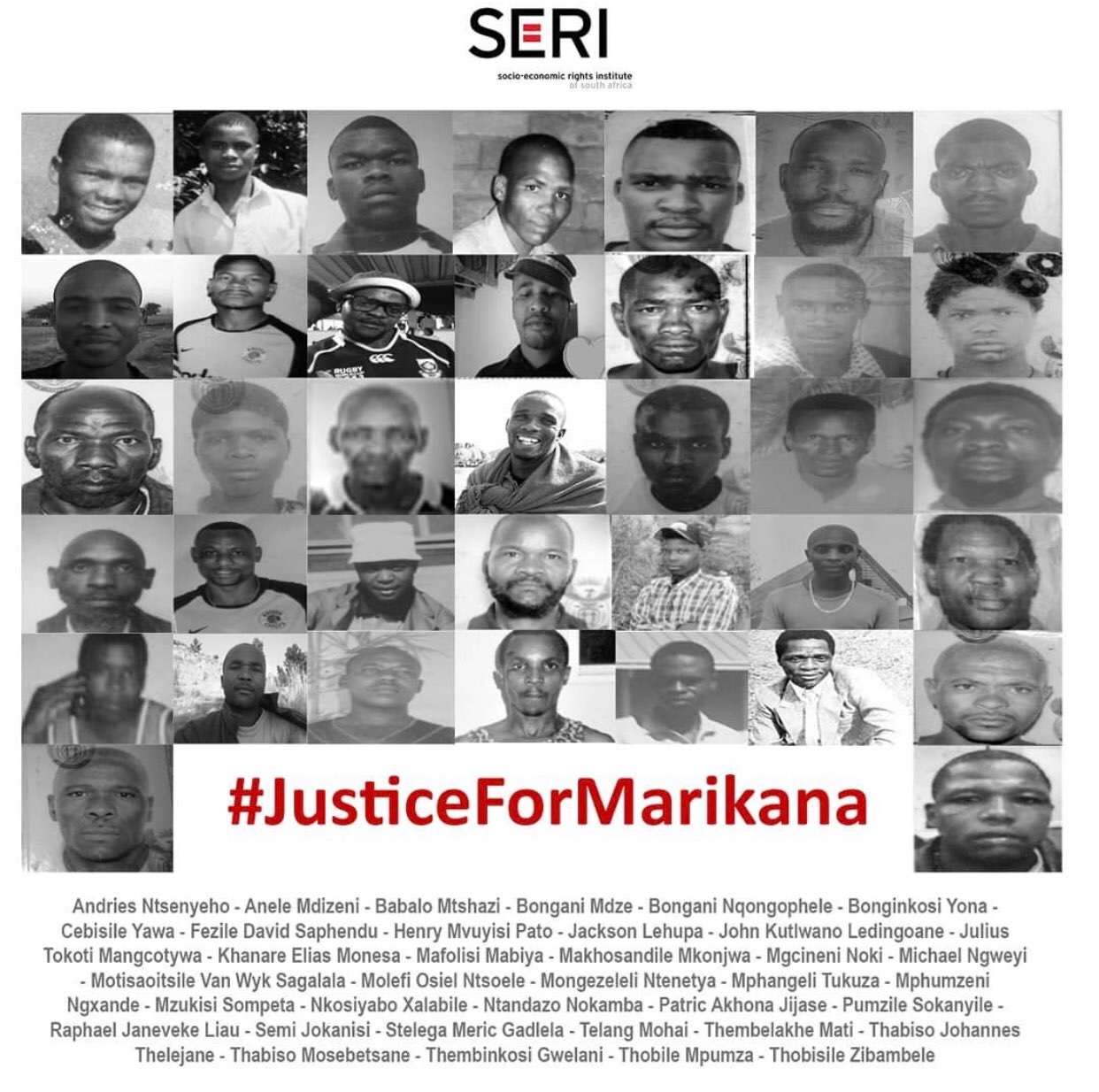

To the contrary, the SACP often provides the terminology and ideological arguments for the ANC’s rubbishing and rebuffing of labour and community struggles. A case in point are its blanket generalizations that refer to civil-society protests as the work of a faceless third-force, agents of regime change, an anti-majoritarian lobby or the so-called anarchist ‘ultra-left.’ Nothing illustrates this like the way the supposed vanguard of the working class actively and passively endorsed the brute force unleashed on workers at Marikana.[2] It even regurgitated and circulated the narrative of the government about that tragic incident above that of the workers.

Source: Bhut’ Masasa

The SACP’s religious adherence to the notion of the national democratic revolution and to the notion that the ANC is the eternal leader of society or so-called disciplined centre of the left—irrespective of its social policy and political economy trajectory and service delivery performance—holds it ransom. It disallows it to be innovative, creative, and daring in examining the ways of reimagining its organizational form and its engagement with state power and alliance and coalition politics.

Hence, discussion of reconfiguring the alliance or repositioning the SACP is confined to ‘modernising’ or refurbishing its alliance with the ANC and related organizations. It is in this sense that Yaqoob Abba Omar likens the SACP’s position on reconfiguration of the alliance to sacrificing divorce for redecoration (Omar, 2022). Throughout its alliance reconfiguration discourse, the SACP hardly considers exploring some kind of united front beyond the traditional congress movement. It has not given serious thought to tapping into already existing forms of self-organization and movement-building in South Africa, by actively participating in the project of building forms of people’s power beyond the ballot and the mechanics of the government. It hardly engages in theoretical and practical work aimed at linking up with the cooperative and solidarity-economy movements and grassroots movements to experiment with cooperative, communal, and social forms of production, distribution, and consumption, as a way of building democracy and socialism from below.

The ideology of the SACP does not prevent it from having its own representation in a parliament of a bourgeoise democratic or right-wing government. As far back as the 1950s, communists such as Brian Bunting and Sam Kahn represented the then Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) in Parliament. Prospects for the SACP becoming a formidable political force, if it were to pursue contesting political power on its own, are there. There has been a decline in the electoral support received by all centrist and conservative parties, the electoral performance of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) has been stable, and civic and social movements that have opted to contest elections on their own have garnered significant numbers of votes. These facts are indicators of the quest of the people for an alternative to the mainstream political parties. Moreover, in municipalities where local SACP branches had the guts to either field independent candidates or contest elections on its own, there are indications of citizens’ positive response to the idea of the SACP standing on its own. A case in point is the fact that, in the 2017 municipality by-elections, the SACP was able to secure seats in the Metsimaholo Local Municipality (MLM) and to take the position of the mayor in a coalition government. This is within the same municipality that, in the 2016 local elections, the position of mayor was occupied by the Metsimaholo Community Association (MCA), which gained one seat, after contesting elections for the first time because of pressure to do so from the community.

This indicates that there are possibilities for the SACP testing and building its electoral strength in the local government sphere, which is effectively the space that is very significant for addressing the immediate and daily needs of communities on the ground for public services and goods. This is also the sphere that experiences an escalating number of protests, which are a combination of self-organization and spontaneity, heralding the formation of some of the civic/social movements and new parties currently involved in local government politics. Participation of the SACP in local government politics on its own will enable it to link up with these organizations, thereby influencing community struggles. The SACP is not short of the political skills needed to engage in such a participation and use it to build the capacity, strength, support-base and confidence for eventual participation in general elections.

One conceivable explanation of the hesitation or even unwillingness of the top echelon of the Party to pursue this option seriously, is that perhaps the Party’s officials and its political elites find it too risky. Firstly, too risky for their political careers or government opportunities and positions, derived from being in alliance with the ruling party. Secondly, it is risky for the public image that the Party receives from being an ally of the ruling party. Thirdly, in the absence of an outright left party or coalition of left parties capable of seriously contesting state power, the split of the votes of the tripartite alliance may lead to South Africa being under the rule of parties on the far right of, rather than left of, the centrist ANC.

Perhaps the leadership of the Party believes that the loss of whatever social and political currency or mileage it derives from its association with the ANC outweighs the possible political gains of contesting elections on its own. However, a revolutionary party cannot afford to be in the comfort zone, nor can it afford to be imprisoned in a specific organizational form or to be a slave to its own tactics and strategies. A progressive, revolutionary party must have the courage to stride where angels fear to tread and be willing to explore and experiment with new modes and approaches to the struggle.

As Tarrow (1982) posits, the risk-averse behaviour of the communist parties contradicts their claim to be unblemished revolutionaries, and it results in strategic rigidity, paralysis, and sudden policy reversals. The reality is that a communist party that seeks to seize or shape or influence state power cannot afford to be fixed and rigid in its choice of strategic and tactical alliances, nor can it afford to be dogmatic about organizational and institutional forms. In a socio-political and economic environment characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity, organizational and tactical agility is a must. At the same time, it is a fact that strategic and tactical reflexes pose a danger to the ideological consistency of an organization, particularly a progressive revolutionary party.

Maintaining the balance between organizational, tactical, and strategic agility and ideological consistency is probably the biggest quandary faced by communist parties that participate in parliamentary and alliance/coalition politics. As a party makes strategic and tactical responses to unfolding events and adapts itself to the ever-changing environment, it is likely to make both gains and losses—politically and otherwise. As much as the party should make all efforts for its essential nature, purpose, and message to be the same, it must accept the fact that strategic and tactical responses to prevailing realities are likely to dictate a change in its organizational form.

The problematic posed by alliance and coalition politics is that the kind of alliances and coalitions that a party enters into may cause a dilution or confusion in its ideo-political identity. The experience of socialist parties within the European Union (EU) highlights this point. The Socialist Group (SG), an alliance of socialist, social-democratic and centrist democratic organizations established in 1953, had since 1979 been either the largest or second largest group in the Common Assembly—the precursor of the European Union (EU). In response to the Single European Act of 1987, which facilitated the codification of the European Political Co-operation, the Socialist Group entered into a cooperation with the European People’s Party (EPP) to attain the majority required by the cooperation procedure. Since then, this left-right coalition dominated the Parliament, with the post of President alternating between the Socialist Group and the EPP (Hix et al., 2001; Lightfoot, 2005). After successful efforts of the national parties that constitute the Socialist Group to organize in the European region outside of parliament, they established the Confederation of Socialist Parties of the European Community in 1974. The Confederation of Socialist Parties of the European Community was succeeded by the Party of European Socialists (PES) in 1992. Consequently, the parliamentary group was renamed the Group of the Party of European Socialists on 21 April 1993. In 1999, the Confederation of the Party of European Socialists was renamed Socialist Group in the European Parliament and given a different logo to distinguish it from the PES European political party.

After the 2009 European election, the group’s members of parliament were reduced to the point where it lost the status it had gained in 2007, as the second largest party in government. Sammut (2019) attributes the decline of electoral support for the socialist and social-democratic parties to factors such as political fragmentation, instability, security issues, low voter turnout, and the increase in nationalism and support for far-right parties. In response to this reality, the Group of the Party of European Socialists sought to include the Democratic Party of Italy, which till then was not an affiliate, as a member of the Group. As the Democratic Party is a “big tent” centrist party with strong influences of social democracy and the Christian left, a new and more inclusive name had to be found. Thus, the group’s president, Martin Schulz, proposed the name Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats on 18 June 2009. However, confusion on the various abbreviations of the name in English (i.e. PASD, PASDE and S & D Group) led to Schultz’s declaration that the group would be referred to as Socialists and Democrats until a final title was chosen. Ultimately, the constitutive session of the party, held on 14 July 2009, adopted the formal name of Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats, and the abbreviation S & D. While it had been associated with the Socialist International when it was called the Socialist Group in the European Parliament, it joined the Progressive Alliance that was established on 22 May 2013, when it became the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats. It is also a member of the board of the Progressive Alliance.

Whereas the Socialist International (SI) is a political international which seeks to establish democratic socialism, the Progressive Alliance is a political international for progressive and social-democratic political parties and organizations. Importantly, the Progressive Alliance was established by former and current members of the Socialist International (SI) as an alternative to the SI. Clearly, the shift from being an associated organization of the SI to being an affiliate of the Progressive Alliance was dictated by the absorption of the Democratic Party and the increase in the number of centrist parties in the alliance. In this sense, the tactical manoeuvre of incorporating the Democratic Party within the alliance served to modulate the socialist current, and to give more traction to the centrist current, within the alliance. Thus, the centre-left orientation of the party was the product of efforts to mediate and harmonise the political and social agendas of socialist, social-democratic and Christian democratic tendencies within the party. One would also imagine that this would have affected its domestic and international policies, in the same way that its earlier coalition with the right-wing EPP would have constrained the policy choices and decisions of the coalition government. For instance, there are likely to be serious tensions in how the socialists, social democrats and Christian democrats would answer and act upon concerns raised by EU citizens on issues such as security, migration and good economic governance (Sammut, 2019).

In the same way that Sammut (2019) proposes that social-democratic parties in Europe should seriously consider and address other possibilities, outside their traditional principles, to reconnect with European citizens, the SACP may have to think and act outside its traditional modes of operation to capture the imagination and support of the populace beyond its traditional congress movement and Marxist-Leninist base. The way forward for the SACP and other non-governing communist/socialist parties should be a comprehensive and holistic strategy that entails active participation in both parliamentary and extra-parliamentary politics to agitate for the socialist cause, expose the inadequacies of reformist projects, build the fighting capacity of the working-class and the underclasses to think and act imaginatively, innovatively, and forcefully to advance a socialist agenda.

This requires that the SACP and other socialist formations free themselves from the vulgar vanguardism wherein the party which ordains itself the intellectual sangoma that knows and sees everything about the present and the future and expects or demands the masses only to shout: “siyavuma!”[3] This calls for the SACP and the entire socialist left to demonstrate, through social practice and tangible campaigns, programmes and projects, that an alternative to capitalism is possible and viable, and that the way out, to move beyond human misery, is the abolition of the current world system based on the production of “value” and its replacement with an egalitarian system that seeks to end the alienation of human beings from their labour, the products of their labour, themselves, and their fellow beings.

The types of alliances, coalitions and movements that the Party is part of can prevent it from pronouncing its class affinities practically—through the policies and programmes it endorses or pushes. To reduce this possibility, the Party must carefully examine the social and political agendas and class affinities of its political allies, and it must focus its alliance efforts on socialist, green, radical feminist and anarchist organisations before it thinks of being in an alliance with centrist and right-wing parties. If, for whatever reason, a communist party enters, as part of a socialist alliance, a coalition government that includes centrist and right-wing parties, it will have more opportunities to exert a socialist agenda both within and outside of government than if it establishes a coalition with centrist organizations on its own.

Importantly, any socialist alliance or alliance of socialists, social democrats and centrists must be based on clear-cut minimum demands and a minimum program. Among several strategic approaches to weaving different political parties and organizations around common strategic and tactical goals, the most prominent is a structured coalition in which different parties and organizations formally agree on the nature, form, and workings of the coalition. A key element of the structured coalition, which must be at the top of the issues agreed upon, is a minimum program that summarises the total goals, strategies, and tactics of the coalition (Schepers, 2020). It is important that the structures of the alliance or coalition or united front agree on and develop a written accord that spells out the terms, scope, principles, processes, and practices of the coalition. In other words, the alliance, coalition or front must have a broad philosophical and ethical framework, an organizational culture, and a clear structure that entrenches and embodies the philosophical-ethical framework and the organizational culture. The socialist/communist party must take the lead in constructing/shaping the minimum demands and program and in monitoring compliance and guarding against deviation from the minimum demands.

The Party cannot afford to rely only on parliamentary structures and processes or a “ladies and gentlemen” arrangement/agreement between socialists/communists and centrists or conservatives. It must build its fighting capacity outside of government and therefore be part of broader movement-building and regular mass action outside of parliament. The social intent of the parliamentary and extra-parliamentary action of a socialist/communist party must be seizure of political power and using that power to advance a social revolution. Anything else will amount to chasing shadows rather than pursuing and realising the socialist/communist society.

The other alternative that the SACP can pursue, which has been adopted by the Portuguese Communist Party, is that of offering support from the outside. In Portugal, the Socialist Party (Partido Socialista) was able to take and retain power without being in a coalition, but with the support from the outside of a structured formal coalition between the Portuguese Communist Party and Ecologist Green Party. Through their longstanding electoral coalition—the Unitary Democratic Coalition—the Portuguese Communist Party and the Ecologist Green Party vote for the ruling party, which also gets support from another left-wing formation, the Left Block (Bloco de Esquerda), which emerged from a merger of several small parties. This Communist-Green coalition and the Left Block hold enough seats in the Portuguese lower house and the Assembly of the Republic to block the right-wing from ousting the Socialist Party from power (Schepers, 2020). However, they have not asked for portfolios in the cabinet/executive of the government of the Socialist Party.

Herein lies the difference between these parties’ support from outside and the SACP’s support of the ANC from outside. The advantages of the Portuguese Communist Party’s strategy are obvious. Firstly, it silenced right-wing elements within the Socialist Party who were willing to either discard the idea of taking power or to enter into a coalition with right-wing parties, rather than accepting a coalition with communists. Secondly, by not requesting or accepting ministerial positions, the Portuguese Communist Party is free to sharply criticise the government (Schepers, 2020) and to protect its members from a situation in which they are co-opted and compelled to implement and defend policies and programmes of the ruling party that are at variance with communist principles.

Another example is that of the Communist Party of Venezuela, which has been part of the Great Patriotic Pole that includes fifteen leftist and centre-left parties. Having frequently criticised Nicolas Maduro’s United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), the Communist Party of Venezuela joined hands, in July 2020, with the Homeland for All Party and several other organizations, to contest elections separately under the umbrella of the People’s Revolutionary Alliance of Venezuela. The Communist Party of Venezuela nonetheless continues to defend the Venezuelan government, led by Maduro’s PSUV, against attacks by the United States and its allies, and the Venezuelan right-wing.

It is highly important that, in its efforts to reposition itself in the socio-political arena, the SACP considers and draws on all these experiences, in a nuanced way, rather than simply confining itself to refurbishing the tripartite alliance or extending and modernising the congress movement.

References

Cushion, S. (2016) A Hidden History of the Cuban Revolution: How the Working-Class Shaped Guerrillas’ Victory. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Hix, S., Kreppel, A. and Noury, A. (2001) “The Party System in the European Parliament: Collusive or Competitive?” Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 41, Apr., pp. 309–331.

O’Malley, S. (2000) “Tripartite Alliance.”

Lightfoot, S. (2005) Europeanizing Social Democracy? The Rise of the Party of European Socialists. London: Routledge.

SACP (2006)“State Power,” Bua Komanisi, Vol. 5, No. 1, May (special ed.).

Schepers, E. (2020) “Communists, coalitions, and the class struggle.”

Sammut, B. R. (2019) The decline of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in European elections (Bachelor’s dissertation).

Tarrow, S. (1982) “Transforming Enemies into Allies: Non-ruling Communist Parties in Multiparty Coalitions” The Journal of Politics. Volume 44, No 4 (Nov. 1982) pp. 924–954.

Notes

[1] “GEAR” is an acronym for Growth, Employment, and Redistribution, a 5-year plan adopted in 1996. [Editor’s note]

[2] This refers to the 2012 Marikana Massacre. Police in the town of Marikana killed 34 striking mineworkers and seriously injured 78 others. [Editor’s note]

[3] A sangoma is a “highly respected healer among the Zulu people.” Among Xhosa- and Zulu-speaking people, siyavuma, which means “we agree,” is “the traditional response when a diviner’s diagnosis meets with approval.” [Editor’s note]

Be the first to comment