by Theresa Henry

Credit: Unistoten Camp Website, February 16, 2020.

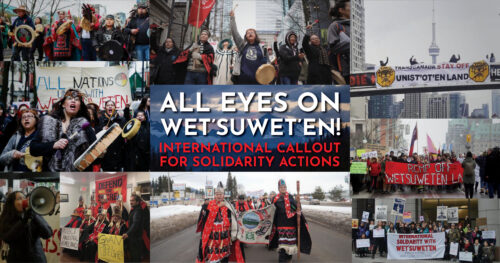

In the late winter and early spring of 2020, Canada erupted in Indigenous-led protests against the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The police had invaded Wet’suwet’en territory in order to evict Wet’suwet’en people and their non-Indigenous supporters who together had stopped construction on the Coastal Gaslink Pipeline.

I was a young, non-Indigenous activist involved in support work for that movement. Ever since, I have been thinking about problems I saw in the movement’s practice, especially in the relationship between Indigenous people and their settler supporters.[1] In particular, I am concerned with an expression of “ally politics” that encouraged supporters to refrain from doing any critical thinking and therefore turned our participation into mere humanitarianism.

The protests largely took the form of blockades at sites of critical infrastructure such as ports, train-tracks, and highways. The “Shut Down Canada” Movement, as it was called, was the first mass movement in British Columbia since protests against the 2010 Olympics broke out in Vancouver. For many young people involved in the movement like myself, it was the first mass movement we had ever been a part of. The movement brought out Indigenous people living in cities, towns, and reserves, a large swatch of multi-racial radical and progressive youth, environmentalists, NGOs and human rights organizations, and socialists of various stripes. The number and energy were amazing to witness.

Blockades Put Focus on Transportation

There had been mobilizations in Vancouver the previous year in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en nation’s defense of their traditional territories, but what was markedly different in 2020 was the sharp focus on transportation infrastructure. The symbolism of this shift was perfect. In Canada, the ports, railroads, and highways conjure up images of Indigenous labor, dispossession, disappearance, and genocide. They conjure up images of poorly paid refugee workers. But they also conjure up an image of a strong, connected, and united Canadian nation.

The focus on transportation, though, was not merely symbolic, as the blockades did interrupt production, losing Canada millions and millions of dollars in a very short amount of time. This more militant, national approach represented the coming into the fore of a current in the Idle No More movement that, according to Nishnaabeg writer, musician, and activist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, was competing with “segments [that] were decidedly against direct action because it makes Canadians angry…and in some cases because it was seen as incompatible with Aboriginal culture.” If these segments existed in the Shut Down Canada movement, they were totally eclipsed.

These developments on the ground may reflect the increasing political and cultural impact of Indigenous Resurgence philosophies that, despite being unique, are connected in “turning away” from seeking recognition from the colonial government.[2] In another place, it would be worthwhile to investigate the dialectic between the development of these philosophies and the militancy of Indigenous nations, particularly their matriarchs and youth. But here I am concerned with another philosophy, and with it an approach to solidarity that appeared as a dominant force in the movement: liberal humanitarianism, its general expression in “ally politics” and in particular in the expression of “showing up as a body.”

By liberal humanitarianism, I mean the idea that non-Indigenous people should support Indigenous sovereignty struggles out of kindness, pity, belief in “equality of opportunity,” or other bourgeois abstractions. The truth is that in Canada, capitalist production is structurally dependent on settler colonialism, and therefore freedom for working class settlers from exploitation is also dependent on abolishing colonial domination.

It is liberal humanitarianism that motivates the “ally” approach in which the non-Indigenous left shows up to merely take directions, because we approach the situation as if it is someone else’s battle and not our own. Over the years, the “ally approach” has concentrated itself down into an even more deferential form that was dominant in this movement. During the blockades, non-Indigenous progressives and radicals who showed up to support the movement were aptly referred to and referred to each other as “bodies” because thinking was not seen to be a necessary element of our role. It is painful to have to describe what is wrong with this approach, but not only is this approach incredibly dehumanizing, and not only does it take the bourgeois division of mental and manual labor to an absurd extreme, it simply does not resonate with what workers were doing and saying at the blockades. That this approach objectifies and is irrelevant to the radical aspects of the working class should alone signal to the left, especially the socialist left, that an immediate revaluation of our theory and strategy is imperative.

The Absurdity of Allyship

It was not until a couple months after the height of the mass movement in which the “bodies” approach gained significance that I witnessed it taken to its illogical conclusion. While there was still significant energy to support Indigenous sovereignty struggles, my partner and I were the members of our organization–a group trying to unite the struggles of Indigenous poor and working class people under the banner of “decolonial socialism”–who were responsible for organizing the residents of a homeless encampment to resist an eviction injunction granted by the Supreme Court. This tactic of resistance had been successful in other “tent cities” in our experience, but leading up to the day of dispersal there was not enough commitment in the camp to refuse the inevitable police raid. The Indigenous leaders of the camp correctly called on the community to help relocate the camp to a location owned by the city, where it would be harder to grant an injunction. I had experience with this approach, as I was part of a similar move in Victoria years prior. I knew that the success of this approach was temporary, but I also knew we had no choice.

On the day of the move, about a hundred allies descended upon the tent city to help people pack up their tents into U-Hauls. Many supporters of the tent city even stayed overnight to bulk up the site so cops wouldn’t come to displace residents during the night. At its best we were engaged in a “tactical retreat,” but because there was no attempt to refuse the injunction, it felt more like we were just doing the cops’ jobs for them.

Central to the political and spiritual life of the camp was a sacred fire that was tended to by an Indigenous elder. When there were no former residents left at the camp, a group of 30 or so supporters stayed to make sure the sacred fire burned out naturally and was not smothered by the police. My comrades and I left to help establish the new camp, worried that the police might be waiting for us at the new location, and so we were shocked to learn later that all of the supporters who stayed were arrested.

That night one of the other camp supporters handed us a flier at the new location and told us about the legal campaign for those arrested at the previous camp (likely a waste of time because people were already out of jail and it is common for these sorts of charges to be dropped). I blankly responded “this isn’t true” to the person because the flier was making it seem like those people got arrested defending residents of the camp. I said something along the lines of “everyone who lived at the camp was already here when those people were arrested.”

Afterwards, my partner and I discussed with our organization that this flier shifted the focus from the people living in the camp fighting for housing to activists who were arrested for a different reason: defending the sacred fire. But even for that reason, which is a good one, the arrests were purely symbolic. The Indigenous elder who was the fire-keeper was not arrested and was able to see that the fire burnt out naturally and that the ashes were taken to the new location to begin a new sacred fire–meaning the police arrested the supporters merely to get them off the property.

It was clear to me that the supporters who got arrested did not stop to think critically about whether what they were doing benefitted the movement for Indigenous sovereignty that had just reached a crescendo in the immediate struggle in front of them. And to make matters worse, they were now trying to come up with a justification for their actions after the fact, one that turned attention away from the struggle of the people they claimed to be fighting for! All of this happened because a group of mostly non-Indigenous people with good intentions failed to conceive of themselves as anything more than “bodies” that were “holding space” for Indigenous sovereignty by putting themselves “on the frontline,” whatever that meant and whether or not it was useful. What a public legal campaign for a group of mostly non-Indigenous people contributes to Indigenous sovereignty, and how any of these arrests benefited the people who were living in the camp, many of them Indigenous, remains a mystery to me.

What is not mysterious is the problems with this deferential approach. There is nothing wrong with showing up to mass movements and taking directions from the leaders based on their philosophy, vision, and theories of freedom and strategic assessments and experience. But the example above shows that there is something seriously wrong with doing this without thinking about what social relations between Indigenous people and the settler left look like when they are not based on either domination or deference. Regardless of the intentions of the supporters who were arrested, their actions made them appear as “good allies.” This is exactly the problem with the ally approach in particular and liberal humanitarianism in general: despite its claim to be about the oppressed, it actually displaced the subjectivity of the movement onto the non-Indigenous “allies.”

The Gulf Between Socialists and Workers

The issue in such sovereignty movements is not the feelings or image of non-Indigenous people. It is the freedom of Indigenous and colonized people all over the world from imperialism. This was clear in a conversation I had with two long-haul drivers at a port blockade I helped organize. They were immigrants from India. They parked their trucks before the blockade, got out, and asked us what we were protesting. We explained to them that we were protesting the RCMP invasion of Wet’suwet’en territory in order to evict them from their land and continue construction on the Coastal Gaslink Pipeline. The workers were immediately sympathetic. They mentioned to us that they had blocked this exact port a couple years previous as a workplace action. They also related to the Indigenous warriors as people who had freed themselves from British colonialism.

The workers asked us how long we would be at the blockade and I gave a guarded answer, because although there was no agreed-upon plan for retreat, there was also no plan for a sustained blockade. The workers pushed me: “will you be here till 7, 8, 9:00 pm?” I didn’t have a straight answer. We weren’t organized enough to have a straight answer. One of the workers said that “if we were serious,” he would “park [his] truck in the middle of the road, blocking that whole highway.” If we were not serious, he would respect the picket line and go home to his family.

Well, we weren’t serious. We couldn’t tell them honestly whether we were planning to stay through the night. The two men left and our blockade lost two valuable comrades: anti-imperialist, rank and file workers. We made the decision shortly after to close up the blockade in a couple of hours.

The success of our blockade was its setting a precedent of expanding from the initial location. Blockades spread around the city and stayed there for days at a time. But the blockade also revealed a gulf between the non-Indigenous left and sympathetic rank and file workers in their thoughts, convictions, and actions. The anti-imperialist and class conscious rank and file longshoremen and truck drivers who respected the blockades as picket lines and who saw the Wet’suwet’en struggle as their own, were far more “advanced” than the non-Indigenous left.

This gulf between workers and socialists became a site of personal tension, as I was working full-time through the blockades, at two different jobs. At my weekday job at a bar, all of my co-workers were watching news of the protests with a general attitude of shock at their expansion and support for the movement, despite the occasional comment on the inconvenience because all the major buses in the east part of the city being re-routed. At my weekend job at another bar, many of the workers, including myself, would show up exhausted in the morning from staying up all night at the blockades or would be tired for their evening shift because they’d been out at the protests all day long.

I remember feeling conflicted for two reasons: I was frustrated that the political organization I was a part of did not have anything at all to say about engaging with the mass movement at the point of production, but was confused about how to bring this up or even what I would say; that I was torn between going to the blockades with my comrades who were choosing to expand the blockades out of the city and my fellow workers who were, obviously, spending their time at the main protest close to our work. This feeling of alienation from organization and class gripped other worker-members of the group too.

In retrospect, I believe this feeling of alienation was a symptom of the disorganization of non-unionized workers. It was the feeling of being able to relate to the movement only as an individual at worst, a member of an organization at best, but never as part of the class. I watched my co-workers push themselves to the point of fatigue to support the movement, but when they left the shop floor and entered the streets, they were not confronted with a liberal humanitarian approach to solidarity.

Working class people, who have the capacity not just to shut down industry but to take control of it and to devote it to the needs of the Earth and humanity, were reduced to “bodies,” and sometimes even happily resigned themselves to the role of automaton. This is because of the hegemony of the “ally approach,” which dominates in the absence of an alternative concept coming from the socialist left. The shortcoming I noticed in my organization, that is, the lack of a strategy to project a theory and practice of anti-colonial solidarity at the point of production, was not unique to us. No socialist group in the city was in the position to take on this responsibility.

No Fundamental Difference

Two years after that mass movement, I am still thinking deeply about what was wrong with the approaches of the non-Indigenous left. On one hand, the “ally” approach of “showing up as a body” is dehumanizing, ineffective and alienating. It is dehumanizing because it reduces people’s capacity to think for themselves. It is ineffective because the hostility towards thinking precludes any critique or disagreement within the movement, and therefore any development of ideas. It is alienating because it does not start from the idea that it is our own freedom at stake, and therefore offers nothing to radical workers, who are in fact very concerned with their own struggle for freedom and see it linked to the overthrow of colonial domination.

But on the other hand, the parts of the non-Indigenous left that reject the ally approach have not yet developed an alternative. For example, when the organization I was in expanded the blockades out of Vancouver and into Coquitlam, a neighboring city, we did so without permission from the Kwikwetlem people, and we were rightfully criticized for this. We were right to not sit around as “bodies” waiting to be told what to do, but we were wrong in transgressing the sovereignty of a nation. Our action ended up replicating the exact dismissal of Indigenous political power that we were protesting, even though it opened up space for the Indigenous youth who came together to take charge of the blockade outside the Vancouver metropolis.

Both the liberal approach and the approach of the organization I was in at the time were inadequate, harmful even. Whereas the liberal approach was purely deferential, the approach of my organization rushed past building relations with both Indigenous nations and workers at the point of production. Although these approaches differed in their motivation and conceived of the non-Indigenous left’s role in different ways, neither of them offered a theory of new social relations between Indigenous people and settlers. The “Shut Down Canada” movement made it clear that a theory of new, more human social relations between occupied and occupier needs urgent elaboration.

ENDNOTES

[1] In British Columbia, it is common among the left to refer to descendants of the European colonizers as “settlers.” The colonial project is seen as an attempt to exterminate and replace the Indigenous population.

[2] See Glen Coultard, Red Skin, White Masks; Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interuptus; Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Always Have Done; Pamela Palmeter, Warrior Life; Jarrett Martineau, Creative Combat.

Be the first to comment