by Andrew Kliman

Marx’s Critique of Darimon in the Grundrisse

On Indirectly Social Labor and the “Impossible Tasks” of Labor Money

Marx’s Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy, written in 1857-58 but unpublished during his life, is his first rough draft of what became Capital a decade later. It consists of a chapter on money and a much longer chapter on capital, preceded by an introduction that focuses on method and on relations between production and other economic processes.

The work proper (apart from the introduction) begins with a lengthy critique of Alfred Darimon’s 1856 book, De la réforme des banques (Banking Reform). Darimon was a prominent follower of and secretary to Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, whose doctrines Marx had criticized in an 1847 work, The Poverty of Philosophy. The main thesis of Darimon’s book was that Britain’s gold standard and France’s bimetallic (gold and silver) standard were to blame for the then-current monetary crises these countries faced, and that the problem could be solved by abandoning metallic money regimes. Marx’s critique of the book takes up about half of the Grundrisse’s chapter on money.

Alfred Darimon

The first section of this article discusses the importance of Marx’s critique of Darimon, as a specific “moment” of his overall critique of Proudhonism. The second section discusses Proudhon’s ideas and influence, and why Marx found them concerning. The third section provides an overview of his critique of Darimon. The three sections that follow this overview discuss particularly important dimensions of Marx’s critique.

Section 4 argues that the issue of what is and isn’t economically possible is central to the critique of Darimon and to all of Marx’s other critiques of Proudhonism and related tendencies. He does not challenge their goals; instead, he contends that it is impossible to achieve these goals by means of the changes in capitalist relations of exchange and income distribution that they propose. Revolutionary transformation of society’s mode of production is necessary.

Section 5 discusses so-called labor money, which Marx’s critique of Darimon deals with at great length. Two key elements of his discussion involve the issue of possibility and impossibility. He argues that labor money itself is impossible—labor-time cannot function as money—and that a labor-money regime could not eliminate the boom-and-bust nature of the capitalist economy by eliminating the ups and downs in the price level associated with booms and busts.

Section 6 considers the concepts of directly and indirectly social labor, which I regard as crucially important to Marx’s understanding of the transformation of capitalist society into communist society. He develops them for the first time in his critique of Darimon. Exploring why it is impossible for labor money and similar monetary reforms to accomplish what is demanded of them, Marx arrives at the conclusion that the root of the problem is that labor in commodity-producing societies is only indirectly, not directly, social.

Section 7 is a brief conclusion. Finally, the article includes an appendix that explicates and breaks down Marx’s critique of Darimon in greater detail. I hope it will be useful especially to readers who wish to understand the finer points of his discussion of monetary theory and policy.

1. The Critique of Darimon and Marx’s Other Critiques of Proudhonism

In my view, the critique of Darimon is significant for several reasons. First, it is among Marx’s most in-depth discussions of Proudhonism.

Second, Marx’s critique of Darimon further develops his critique of Proudhonism even in those instances in which it addresses a matter already discussed in The Poverty of Philosophy. Marx’s critique of Darimon does not merely repeat what he had written a decade earlier. For example, both texts argue that systems of equivalent exchange are incapable of realizing their goals; both stress that fluctuations of commodities’ prices around their values or average prices cannot be eliminated; and both argue that money is a necessary feature of commodity-producing society that cannot be abolished within it. But The Poverty of Philosophy’s treatment of these matters reflects the fact that it was written and published in a hurry. Marx began to work on it in January 1847; by April, it was already at the printshop. In contrast, even though the critique of Darimon is certainly not a finished product either stylistically or theoretically, it develops the arguments at greater length and with greater care and precision than The Poverty of Philosophy does, and there is much less stating of conclusions unaccompanied by supporting argument.

Third, the contents of the two critiques differ substantially, largely because the books that they are responses to differ in the same manner. The Poverty of Philosophy is wide-ranging, while the critique of Darimon focuses exclusively on money—the metallic standard, monetary policy and monetary crises, other forms of money (especially labor money), the necessity of money in societies that produce and exchange commodities, and the connection between money and the indirectly social character of labor in such societies. It is also clear that Marx’s knowledge and understanding of monetary policy and crisis had developed greatly during the intervening decade. Proudhonism had developed as well. It was not until after the 1848 French Revolution (and thus, after the publication of The Poverty of Philosophy) that Proudhon and his followers began to call for crédit gratuit (free credit; i.e. zero-interest credit) and the establishment of a Bank of Exchange. For all these reasons, much of what Marx says in his critique of Darimon was not present at all in The Poverty of Philosophy.

Fourth, the critique of Darimon articulates, and develops to varying degrees, many arguments and ideas to which Marx returns in later writings. His 1859 Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (CCPE) and all three volumes of Capital discuss money and finance. Some of what he says in them—about functions of money, different forms of money, the historical development of money, financial issues, the split between money and other commodities, and the consequences of this split (including the separation of sale and purchase and how it makes crises possible)—is anticipated in the critique of Darimon. In addition, several arguments and ideas in the critique of Darimon that pertain specifically or especially to Proudhonism and similar tendencies also appear in later works:

(a) The idea that guides the overall structure of Marx’s discussions of the value-form in the CCPE and Capital—that money is a further development of the contradiction between value and use-value present in every commodity—appears in the critique of Darimon (as a single sentence, sandwiched in between quotations from newspapers).

(b) The discussion of labor money in the critique of Darimon, and Marx’s main conclusions, reappear in the CCPE, though in a quite different form.

(c) The critique of Darimon develops at some length the idea that capitalist society replaces subordination (“dependence”) of some people to others with universal subordination of people to things. This theme reappears in the section on the “fetishism of the commodity” in the first chapter of Capital, volume 1, and elsewhere.

(d) The concepts of directly and indirectly social labor, which are developed first in the critique of Darimon, later appear in the CCPE, Capital, and Marx’s 1875 Critique of the Gotha Program.

(e) Marx compares the Proudhonist call for an exchange system in which, in effect, all commodities are money to a Catholicism in which all Catholics serve as pope. The analogy appears first in his critique of Darimon, and then in chapters 1 and 2 of Capital, volume 1.

2. Proudhon’s Ideas and Influence

Proudhon was a French worker and radical thinker. In 1840, he published What Is Property?, which contained his famous formulation “Property is theft!” He espoused anarchism (absence of centralized government) and “mutualism” (economic coordination though a network of workers’ associations). He wanted an economic system that retains market capitalism’s exchanges between individuals, and contractual rights and obligations, but which differs from market capitalism in that exchanges would be “equivalent”—products of equal value (determined by labor-time) would exchange one-for-one. After the 1848 revolution in France, Proudhon also advocated free credit and the establishment of a Bank of Exchange to provide it and to regulate exchange.

Proudhon and Marx knew one another personally. Their relationship was friendly at first. When Marx lived in Paris, between late 1843 and early 1845, he and Proudhon “often spent whole nights discussing economic questions,” according to Frederick Engels. The Holy Family, which Marx and Engels wrote in late 1844, and which appeared in early 1845, contains a very lengthy critical defense of Proudhon’s ideas, written by Marx. It declared: “Not only does Proudhon write in the interest of the proletarians, he is himself a proletarian, an ouvrier [manual worker]. His work is a scientific manifesto of the French proletariat.”

However, as Engels also recounted, the views of Proudhon and Marx “increasingly diverged,” and the 1846 publication of Proudhon’s The Philosophy of Poverty “proved that there was already an unbridgeable gulf between them.”[1] Marx’s severely critical response to it, The Poverty of Philosophy, appeared the following year. A decade later, he again criticized Proudhonism, in the Grundrisse’s critique of Darimon, although this remained unpublished. Later works that Marx did publish, the CCPE and especially Capital, also include criticism of Proudhonism. In particular, section 3 of the first chapter of Capital, on “the value-form, or exchange-value,” is a response to Proudhonist and other proponents of monetary reform.[2] And once the International Workingmen’s Association (the First International) was established in 1864, Marx fought the influence of Proudhonism within it for several years.

Proudhon’s ideas had a wide influence. They were a key influence on Russian anarchists Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. They also influenced radical nationalists in Italy, federalists in Spain, and syndicalists throughout southwestern Europe. Bakunin called Proudhon the “master of us all.” In France, Proudhonism became the dominant socialist tendency, and its dominance affected the political orientation of the International, since about one-third of the International’s voting members belonged to the French section.

Why did Marx find Proudhonism so concerning? Common explanations are that he was intolerant of differing views and/or that he wanted control over the International. A more charitable explanation, and one that I think is better supported by the evidence, is that Proudhon’s body of thought was bad—both theoretically inadequate and harmful—and that the harm it could cause was exacerbated by the fact that it was so influential, notwithstanding its inadequacy.

Or, perhaps, because of its inadequacy. Joan Batten Wood characterized the link between the inadequacy and the popularity of Proudhon’s thought as follows:

Proudhon’s appeal to the masses was not in the form of a tightly-woven system of thought; he was never single[-]minded enough to formulate a theory that did not contain contradictions. His antinomical method was sufficiently dense to discourage many readers, and his style was rambling, vague, and all-embracing—full of characteristics of the autodidact. Curiously, these very qualities were what endeared him to his public. [pp. 23-24]

Despite this, Wood claimed that Marx fought against the influence of Proudhonism within the International because he wanted “complete control” (p. 40. p. 47).

But what about the pernicious effects of Proudhonism? It is illuminating to consider some of the ideas that were bound up with Proudhon’s version of anarchism and mutualism, ideas that his followers struggled for within the First International. They opposed strikes by workers because Proudhon thought that strikes “involve an element of coercion and … that any increase in wages which may result from them will be offset by a general increase in prices.”[3] They opposed the International’s resolution calling for a legal limit to the length of the workday, on the grounds that a legal limit infringes on workers’ and employers’ freedom to contract with one another. The Proudhonist version of anti-statism also included opposition to other struggles to enact new laws that would improve workers’ lives, and to public education. And because of his opposition to “nationalism,” Proudhon had opposed Poland’s struggle for independence from Russia; accordingly, his followers in the International fought against its adoption of resolutions that would have supported Polish independence and condemned Tsarism.[4]

Marx himself attributed the struggle within the International to the harmful effects of Proudhonism. In an October 9, 1866 letter to his friend Ludwig Kugelmann, he wrote:

The Parisian gentlemen … spurn all revolutionary action … and therefore also that which can be achieved by political means …. Beneath the cloak of freedom and anti-governmentalism or anti-authoritarian individualism these gentlemen … are in actuality preaching vulgar bourgeois economics …. Proudhon has done enormous harm. His pseudo-critique and his pseudo-confrontation with the Utopians … seized hold of and corrupted first the “jeunesse brillante” [bright youth,] the students, then the workers, especially those in Paris, who as workers in luxury trades are, without realising it, themselves deeply implicated in the garbage of the past.

In light of all this, it seems to me that when commentaries present Marx’s theoretical-political opposition to Proudhonism solely or mostly as a matter of his supposed intolerance or desire for control, this says more about the commentators’ own attitudes to ideas and their importance than it says about the historical record.

Eventually, the influence of Proudhonism, especially its “orthodox” version, waned within the International, but not because of Marx’s arguments against it. According to George Comninel, it waned because the French working class began to move in an anti-Proudhonist direction: “a wave of strikes—in which active support by the [International] played an important role”— began in 1867 (p. 72).

3. Overview of Marx’s Critique of Darimon

About half of the Grundrisse’s chapter on money (from p. 115 to approximately p. 173) is devoted to the critique of Darimon’s book and of Proudhonist and other proposals for monetary reform in general.[5] This subdivision of the chapter, which is my own, is approximate and interpretive, partly because the chapter lacks section headings or other indications of its structure, and partly because Darimon’s name is not mentioned after p. 134.

The first 20 pages of Marx’s critique hew rather closely to matters discussed in Darimon’s book, especially the metallic standard and liquidity crises.[6] Darimon argued that the British and French central banks (Bank of England, Bank of France) were “impotent” in the face of the then-current monetary crisis, because these countries adhered to a metallic standard: “The root of the evil is the predominance which opinion obstinately assigns to the role of the precious metals in circulation and exchange” (pp. 1-2 of Darimon’s book; quoted on p. 115). If the metallic standard were abolished, however, such crises could be eliminated. The volume of central banks’ lending would not be constrained by their need to maintain adequate metal reserves. They could provide a sufficient amount of the free credit that the Proudhonists called for.

Marx engages in technical and often detailed argumentation to rebut these claims. He starts by criticizing Darimon’s handling of recent data on the Bank of France’s asset portfolio. Darimon’s analysis of the data, he says, “betrays the bungling of the dilletante” who fails to understand the distinction between money and credit (p. 116). Yet the bungling was also partly an “intentional” effort to confirm Darimon’s “preconceived opinion” that France’s adherence to the metallic standard prevented the Bank from extending sufficient credit (p. 116, p. 119).

Marx acknowledges that the metallic standard can exacerbate a shortage of liquidity, but he concedes little else. Where Darimon attributes a certain aspect of liquidity crisis—such as insufficient supply of credit, high interest rates, and outflow of gold abroad—to the existence of the metallic standard, Marx endeavors to show that its actual causes are different. He also points out that Britain experienced monetary crises in 1809 and 1811, even though the Bank of England was then issuing banknotes that could not be converted into gold. Because these “crises did not stem from the convertibility of notes into gold (metal)[, they] could not be restrained by the abolition of convertibility” (p. 126).

Thus, elimination of the metallic standard would not solve the problems it is meant to solve. Marx himself attributes these problems mainly to the existence of money—not a particular form of money or particular monetary system, but money as such, any monetary system—and, more importantly, to the underlying, bourgeois, social relations of production that give rise to money and make its existence unavoidable. An alternative monetary system may be able to eliminate some forms of monetary crisis that a metallic system cannot, but since there are “contradictions inherent in the money relation,” alternative monetary systems will “reproduce these contradictions in one or another form” (p. 123).

Because Darimon himself had failed to situate the metallic standard and its liquidity crises within the wider and more elemental context of money and bourgeois relations of production, Marx accuses him (fairly) of begging the question. Darimon assumed what he instead needed to demonstrate: that monetary crises as such would disappear if the metallic standard were abolished but capitalist production and exchange relations continue to exist.

For Marx, this was the fundamental theoretical issue at stake. But because Darimon’s book had not engaged with this issue, Marx’s detailed, point-by-point critique of the book was likewise failing to do so!

Marx therefore changes course. In the remaining two-thirds of (what I regard as) his critique of Darimon, he discontinues his point-by-point responses to Darimon’s arguments and his technical discussion of the functioning of the metallic standard. He makes explicit what was only implicit in Darimon’s stated positions. He restates the issues in terms of basic concepts of economic theory, freed from contingent complexities of the then-current monetary system. And he addresses head-on the question that Darimon and other Proudhonists “never even raise … in its pure form,” about “whether the different civilized forms of money—metallic, paper, credit money, labour money (the last-named as the socialist form)—can accomplish what is demanded of them without suspending [aufzuheben: abolishing] the very relation of production which is expressed in the category money” (p. 123).

Once Marx discontinues his detailed responses to Darimon’s arguments, the remaining forty or so pages of his critique tackle this question. To answer whether any alternative monetary system “can accomplish what is demanded,” Marx focuses mostly on the case of labor money (which he also calls “time-chits”). His in-depth discussion of this form of money also leads him to consider a network of related issues. These include: the properties (functions) of money; the split between money and other commodities; the relation between money, commodity exchange, and the existence and production of commodities; the alienation and fetishism (“[p]ersonal independence founded on objective dependence” (p. 158)) characteristic of societies in which exchange relations and money predominate; and the indirectly social character of labor in a commodity-producing society versus its directly social character in a society in which production is “communal.” Sections 5 and 6, below, will comment in greater detail on Marx’s discussions of labor money and the final two issues.

4. The Relation of Economic Possibility to Revolutionary Theory and Practice

What is possible in a capitalist society, and what is not? In which ways, and to what extent, can a capitalist society be different from what it currently is?

These are the central questions that Marx took up in his critiques of Proudhonism and similar tendencies in the radical movement. They pervade the critique of Proudhon in Marx’s 1847 The Poverty of Philosophy; his 1857 critique of Darimon; the criticism of John Gray’s labor-money proposal in his 1859 CCPE; section 3 of the first chapter of Capital (published in 1867 and in later editions), on “the value-form, or exchange-value,” which is a response to Proudhonist and other proponents of monetary reform; and Marx’s 1875 Critique of the Gotha Program.

In a December 28, 1846 letter to Pavel Vasilyevich Annenkov, Marx commented on the new book by Proudhon that he would respond to a few months later, in the Poverty of Philosophy. He wrote that Proudhon “does what all good bourgeois do”: they criticize how competition and other features of bourgeois society exist “in practice” while accepting them, unquestioningly, “in principle.” “What they all want is competition without the pernicious consequences of competition. They all want the impossible, i.e. the conditions of bourgeois existence without the necessary consequences of those conditions.” They fail to criticize the “conditions of bourgeois existence”—as such, in principle—because they regard these conditions as natural or inevitable and can therefore see no alternative to them.

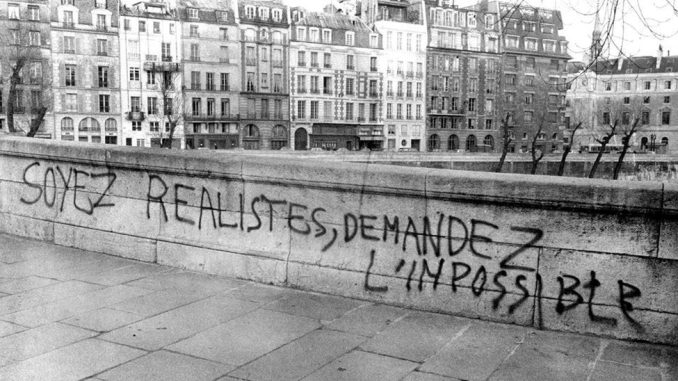

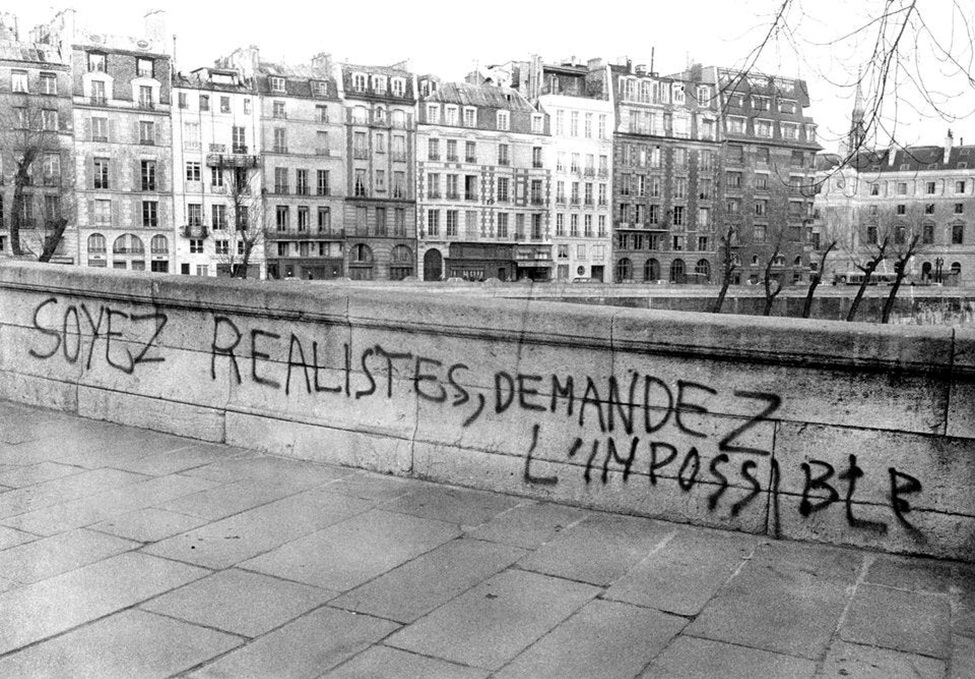

Since this argument would become central to Marx’s critiques of various radical tendencies over the next three decades, it may be helpful to unpack it. Marx was saying that (a) Proudhon and similar thinkers want to eliminate certain features of present-day society, such as competition (as it actually exists). But (b) the features they want to eliminate are just symptoms of deeper problems—“necessary consequences” of underlying social conditions. However, (c) they fail to fully appreciate this cause-effect relation, and thus (d) they refrain from calling for the elimination of the underlying conditions. Yet (e) it is impossible to eliminate the necessary consequences of these underlying conditions without eliminating the conditions themselves. So (f) they demand the impossible. (During the May 1968 revolt in Paris, “Be realistic, demand the impossible” was proudly put forward as a slogan.)

Photo: Gérard-Aimé, “Mai 68, Les Murs Ont La Parole” (May ’68, The Walls Have the Floor). The slogan means “Be realistic, demand the impossible.”

Thus, Marx’s criticisms of Proudhonism and similar tendencies were not mainly criticism of their goals. He largely endorsed at least their ultimate goals (e.g., he wanted to eliminate money and the state). His main criticisms were about the means by which they try to achieve their goals. These means cannot accomplish what they are meant to accomplish. So the reason that Marx stressed the need for revolutionary changes to what he here called “the conditions of bourgeois existence,” and later called the capitalist mode of production, was not that his own goals were different or more far-reaching than the goals of those he criticized. Instead, what he was stressing is that revolutionary changes in the mode of production are needed in order for their own goals to be realized.

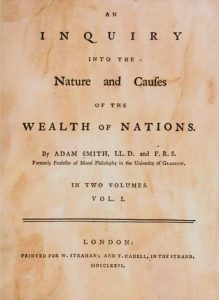

In the Poverty of Philosophy itself, Marx argues that Proudhon had put forward an “equalitarian application” of David Ricardo’s theory that commodities’ values are determined by the amounts of labor bestowed on them, and that John Bray (among others) had previously done so as well. In an 1839 book, Bray had proposed, as a transitional social measure, a system of exchange governed by labor-time; any two products that took equal amounts of labor to produce would exchange one-for-one. After quoting Bray at great length—2000 words—Marx argues that, if his proposal were put into practice, its actual effect would differ from its intended effect. Ultimately, it would reproduce the flaws of existing society, including “[o]verproduction, depreciation, excess of labor followed by unemployment.” The core problem, Marx concludes, is that Bray shared with “the bourgeois” the false belief that “individual exchange can exist without any antagonism of classes.” What he failed to see is that the equalitarian system of exchanges between individuals that he proposed “is itself nothing but the reflection of the actual world; and that therefore it is totally impossible to reconstitute society on the basis of what is merely an embellished shadow of it.”

In the Grundrisse, several pages into his critique of Darimon, Marx abruptly interrupts his lengthy rebuttals to Darimon’s arguments against the metallic standard, in order to pose “the fundamental question” (p. 122). He suggests that it is impossible to revolutionize relations of production or the corresponding relations of distribution by means of “tricks of circulation” (i.e., tricks to reform the process of monetary exchange) that avoid the “violent character” of the needed changes in the relations of production and distribution themselves:

Can the existing relations of production and the relations of distribution which correspond to them be revolutionized by a change in the instrument of circulation, in the organization of circulation? … Can such a transformation of circulation be undertaken without touching [anzutasten: encroaching upon] the existing relations of production and the social relations which rest on them? If every such transformation of circulation presupposes changes in other conditions of production and social upheavals [i.e., if the answer is “no”], there would naturally follow from this the collapse of the doctrine which proposes tricks of circulation as a way of … avoiding the violent character of these social changes, and … of making these changes appear to be[,] not a presupposition[,] but a gradual result[,] of the transformations in circulation. … [Can] the different civilized forms of money—metallic, paper, credit money, labour money (the last-named as the socialist form)— … accomplish what is demanded of them without suspending [aufzuheben: abolishing] the very relation of production which is expressed in the category money …? [pp. 122-123]

Some 20 pages later (pp. 145-146), Marx returns to the issue of what is and isn’t possible. He says that it is impossible to eliminate the “complications and contradictions” that result from the very existence of money by replacing one form of money with a different one. Yet abolition of money is not the solution, because it is

also … impossible to abolish money itself as long as exchange value remains the social form of products.[7] It is necessary to see this clearly in order to avoid setting impossible tasks, and in order to know the limits within which monetary reforms and transformations of circulation are able to give a new shape to the relations of production and to the social relations which rest on the latter.

Marx’s point is that Darimon and other monetary reformers want their proposals to accomplish the “impossible task” of abolishing money even as present-day relations of production remain in existence. Abolition of money requires changes in the relations of production and associated social relations. Once again, he is trying to bring about the “collapse” of theories that avoid the “violent character” of the social changes that are needed.

Marx’s critique of Darimon also contains another significant discussion of impossibility, in connection with the specific way in which Proudhon and Darimon wished to abolish money. They wanted to eliminate the privileged role that gold and silver played under the metallic standard, to “degrade them to the rank of all other commodities” (p. 126), as Marx puts it. But the degradation of gold and silver is, in effect, the

elevat[ion of] all commodities to the monopoly position now held by gold and silver. Let the pope remain, but make everybody pope. Abolish money by making every commodity money and by equipping it with the specific attributes of money. The question here arises whether this problem does not already pronounce its own nonsensicality, and whether the impossibility of the solution is not already contained in the premises of the question. [pp. 126-127]

Marx is making two points here. First, money as such (the pope) is not abolished under the Proudhonist proposal. It continues to exist, though in a different form. Second, elevating all commodities to the status of money (“mak[ing] everybody pope”) is an impossible, unrealizable demand. It is just as impossible for all commodities to function simultaneously as money as it is for every Catholic to serve as pope at the same time. Just as elimination of the papacy would require the elimination of Catholicism, elimination of the social ills that the Proudhonists attributed to money’s privileged status would require the elimination of commodity production and exchange.

In Capital, vol. 1, Marx returned to this cool analogy twice. In the third section of chapter 1, on “the value-form, or exchange-value,” he discussed the contradictory relationship between one single commodity that is directly exchangeable for all other commodities, and all other commodities, which can be exchanged only for it, not with one another. He showed that this contradiction arises out of, and is unavoidable because of, a more elemental contradiction between value and use-value that is present in every commodity. The contradiction between money and other commodities is already contained, in embryonic form, within each commodity. Having completed this demonstration, Marx attached a footnote (26) on the “philistine utopia … depicted in the socialism of Proudhon.” He compared “the illusion … that all commodities can simultaneously be imprinted with the stamp of direct exchangeability” to the notion that “all Catholics can be popes.”

In Chapter 2, a similar footnote (4) discussed “petty-bourgeois socialism, which wants to perpetuate the production of commodities while simultaneously abolishing the ‘antagonism between money and commodities.’” Marx commented that “[o]ne might just as well abolish the Pope while leaving Catholicism in existence.”

In 1875, when two socialist parties in Germany united on the basis of the Gotha Program they drew up, the issue of what is and isn’t possible surfaced again. This time, clarity about the issue, and getting it right, were not just theoretical imperatives for Marx. They were immediate political imperatives as well. He opposed not only the Program, but also the unification of the parties on its basis, largely because of its theoretical “retrogress[ion]” (see end of discussion of point 3).

In this case, the division was not between Marx and Proudhonism, but between Marx and the doctrines of Ferdinand Lassalle. And the issue was not whether it is possible to eliminate money and monetary relations in the absence of a revolutionary transformation of society’s relations of production. But the main issue at stake was similar enough: whether it is possible to fundamentally change relations of (income) distribution in the absence of revolutionary transformation of the relations of production.

The Program did not actually say that this is possible, but Marx regarded it as unacceptable because it failed to say the opposite. It “ma[d]e a fuss about so-called distribution and put the principal stress on it.” It called for “a fair distribution of the proceeds of labor” without making clear what would be needed to advance beyond the present-day relations of distribution. That is, it failed to make clear that relations of distribution that are “fairer” than those of capitalism are impossible unless capitalism’s relations of production are replaced by communist ones—labor that is directly social; products that are only use-values, not values as well; producers who produce collectively instead of exchanging products with one another; and common ownership of the means of production. By calling in the abstract, outside this context, for fundamental change in individuals’ rights to appropriate the “proceeds of labor,” the Program ignored the fact that “[r]ight can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development conditioned thereby.”

Karl Marx

Because it failed to say so much of what, in Marx’s view, needed to be said, he denounced the Program for “perverting the realistic outlook, which it cost so much effort to instill into the Party but which has now taken root in it, by means of ideological nonsense about right and other trash so common among the democrats and French socialists.” He therefore opposed the unification of the two parties as well.

5. Labor Money

As I noted earlier, once Marx’s critique of Darimon abandons the strategy of responding to his arguments against the metallic standard point-by-point, the remainder of the critique directly engages with what Marx regards as “the fundamental question”: whether any alternative monetary system could accomplish what Darimon and other monetary reformers demand of them. Yet, instead of surveying the gamut of alternative monetary systems, Marx focuses largely on the special case of labor money. Why?

By focusing on this special case, he confronts his opponents at their strongest point. If any monetary system could accomplish what Darimon and other monetary reformers demand of them, the labor-money system would be that system. Here’s why:

Proudhonists wanted to abolish “the predominance … of the precious metals” because they wanted to eliminate the decline in commodities’ prices (in terms of gold or silver) that occurs during economic downturns, as well as the consequences of declining prices—the fall in income experienced by sellers of commodities, debts that they can no longer repay, and so on. Yet, as Marx points out, a decline in prices is just a special case of the general problem: commodities’ prices fluctuate. In particular, prices rise during booms and fall during busts. So the underlying issue is whether price fluctuations can be eliminated. This would mean that a commodity’s price always equals its average price (around which, at present, it fluctuates) or, in other words, that its price always equals its value.[8] That is precisely what labor money promises and seems to ensure.

If, for example, labor money takes the form of banknotes, a labor-money system seems to promise that a producer who expends x hours of labor to produce a commodity can sell it to the central bank in exchange for an x-hour banknote. They can then exchange the banknote for any other commodity that has also taken x hours of labor to produce and that is therefore priced at x hours. The value of any commodity (the amount of labor needed to produce it) thus seems immediately to be its price as well; commodities whose value is x hours are sold to and bought from the central bank at a price of x hours. It is then “self-evident that the mere introduction of the time-chit does away with all crises, all faults of bourgeois production. The money price of commodities = their real value; demand = supply; production = consumption; money is simultaneously abolished and preserved” (p. 138).

(The equality of demand and supply is a logical implication of the equality of price and value. If the demand for a commodity is greater or less than the supply, its current price will deviate from its average price. But if the commodity’s current price always equals its average price (here, its value), there are no such deviations and thus no imbalance between demand and supply. The equality of production and consumption to which Marx refers seems to be the same thing formulated slightly differently. If demand always equals supply, then there is never overproduction, production in excess of “consumption” (purchases of goods and services).)

However, Marx points out that these happy consequences of a labor-money system become self-evident only on the basis of its proponents’ assumption that “annulling the nominal difference” between value and price likewise “remove[s] the real difference and contradiction” between them (p. 138). He shows that it is an “illusory assumption” (p. 138).

What he means by the “nominal difference” between price and value is the fact that a commodity’s price expresses (or measures) its value in terms of gold or silver, instead of in terms of labor-time. What he means by the “real difference” is the fact that prices and values differ quantitatively. To show that annulment of the former difference does not remove the latter one, Marx considers how a labor-money system would function in the context of rising labor productivity, a standard feature of modern economies. Would the quantitative relation between price and value remain stable? Or would the increases and decreases in commodities’ prices, relative to their values (or average prices), which plague economies on a metallic standard, also plague economies that have a labor-money system?

If labor money took the form of gold (or another produced commodity), its value would fall as productivity in the gold industry rose, since less labor would be needed to produce a given amount of gold. If productivity doubles, a gold bar that took 100 labor-hours to produce will be worth only 50 labor-hours. That is, only 50 labor-hours will now be needed to produce identical gold bars, so they—as well as the “100 labor-hour” gold bar—can now purchase only 50 labor-hours’ worth of products (which is only half as many products as before, assuming that the productivity increase is confined to the gold industry). Conversely, the prices of products, in terms of labor money, have doubled: originally, 100 labor-hours’ worth of products could be sold for one gold bar; now they can be sold for two gold bars.

If, however, labor money took the form of paper banknotes (or other tokens), a 100 labor-hour banknote would always purchase products that require 100 labor-hours to produce—for example, four “items.” But if productivity doubles throughout the economy, 100 hours of labor now produce eight “items,” so a 100 labor-hour banknote can purchase eight “items” instead of four.[9] Conversely, the prices of products, in terms of labor money, have fallen in half: originally, eight “items” could be sold for two 100 labor-hour banknotes; now they sell for only one.

Thus, commodities’ prices would rise and fall in terms of labor money, just as they rise and fall in terms of gold money, token money, and so forth. And thus, if labor money (either commodity money or token money) were to serve as the measure of value, commodities’ prices would continue to rise and fall in relation to their labor-money values.

Marx makes several other criticisms of labor money as well:

First, numerous phenomena, not just rising productivity, would cause prices to fluctuate in a labor-money system. In particular, a labor-money system would not stop forces that lead to economic booms and busts from manifesting themselves in the form of a general rise in prices during upturns and a general fall during downturns. “[T]he amount of labour time objectified in a commodity would never command a quantity of labour time equal to itself, [… but …] more or less, just as at present every oscillation of market values expresses itself in a rise or fall of the gold or silver prices of commodities” (p. 139).

Second, the very idea of labor money is senseless and self-contradictory. Because commodities’ prices would continue to differ quantitatively from their values, “[c]ommodity A, the objectification of 3 hours’ labour time, is = 2 labour-hour-chits; commodity B, the objectification, similarly, of 3 hours’ labour, is = 4 labour-hour-chits” (p. 139). But this implies that 2 labour-hour-chits are equal to 4 labour-hour-chits, which isn’t possible.

Third, the preceding observation leads Marx to formulate a key tenet of his theories of value and money: “Because price is not equal to value, therefore the value-determining element—labour time—cannot be the element in which prices are expressed …. Price as distinct from value is necessarily money price” (p. 140, emphasis omitted). Or, put in terms of the preceding example: because 3 labor-hours is not equal to 2 labor-hours or to 4 labor-hours, the prices of commodities A and B cannot be measured in terms of quantities of labor-time; these prices have to be measured in terms of some third thing separate from the two commodities—that is, measured in terms of money.

Fourth, it follows immediately that it is “impossible to abolish money itself as long as exchange value remains the social form of products. It is necessary to see this clearly in order to avoid setting impossible tasks, and in order to know the limits within which monetary reforms and transformations of circulation” are able to alter relations of production or other social relations based on them (pp. 145-146).[10] This is something that John Gray, for example, did not see clearly. His labor-money proposal was intended precisely to abolish money without abolishing value, commodities, or commodity production.

Fifth, after expounding at some length on the split between money and other commodities, and on the special functions that money performs in relation to other commodities, Marx returns (on p. 153) to the topic of labor money, this time considering the role of the central bank in a labor-money system. He argues that, for the system to work, “the bank would [need to] be not only the general buyer and seller, but also the general producer” (p. 155)—that is, it would have to be the buyer and seller of all commodities and be in charge of their production. But this implies the abolition of commodity production. The bank would either be “a despotic ruler of production and trustee of distribution” or it would merely be “a board which keeps the books and accounts for a society producing in common” (pp.155-156).

6. Directly and Indirectly Social Labor

As we have seen, Marx’s critique of Darimon poses the question of whether any of the different forms of money, including labor money, can “accomplish what is demanded of them without suspending [aufzuheben: abolishing] the very relation of production which is expressed in the category money” (p. 123). He argues that they cannot. But what does he mean by abolishing “the very relation of production which is expressed in the category money”? Is this just a flowery way of saying “abolishing money”? Or, perhaps, “abolishing the relation of production that the term ‘money’ expresses”?

I do not think so. Money itself is not a relation of production. As Marx says, it expresses (manifests, represents) a relation of production. In addition, the paragraph in question criticizes Proudhonists’ focus on money and its circulation to the exclusion of underlying relations of production. So, what is the relation of production that, in his view, money expresses, the relation that must be abolished? I believe it is indirectly social labor, the fact that workers’ labor in commodity-producing societies is only indirectly social, not directly (immediately) social.

Detailed consideration of what Marx says about directly and indirectly social labor in several other texts, not just in his critique of Darimon, would be needed to substantiate this claim adequately. But I hope that the following remarks will serve, among other things, as prima facie substantiation.

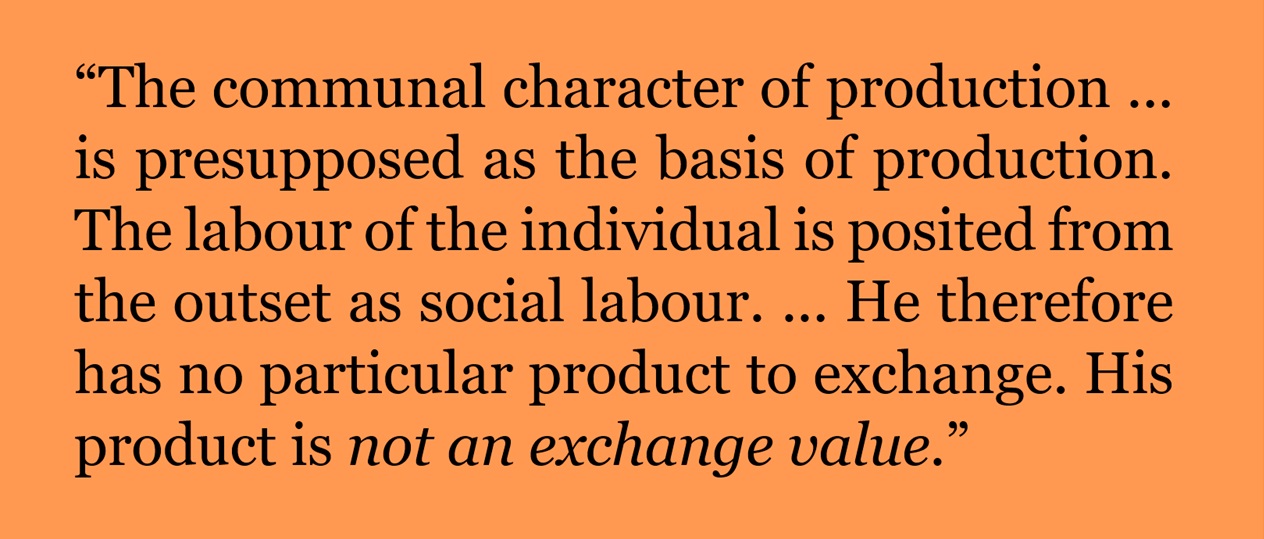

Marx’s critique of Darimon is the first text in which he develops the concepts of directly social labor and indirectly social labor. It does not use those exact terms, but the concepts are undeniably present. Near the very end of this critique, he says that, in a society that produces communally, “[t]he labour of the individual is posited from the outset as social labour” (p. 172). He also says that, in commodity-producing societies, “individuals … produce only for society and in society[, … but] production is not directly social, is not ‘the offspring of association’” (p. 158). “Labour on the basis of exchange values presupposes, precisely, that neither the labour of the individual nor his product are directly general; that the product attains this form only by passing through an objective mediation by means of a form of money distinct from itself” (p. 172).

Marx’s argument that (exchange-)value and labor based on it presuppose that labor is not directly general will reappear (in contrapositive form) in the Critique of the Gotha Program: in neither phase of communist society “does the labour employed on the products appear … as the value of these products …, since now, in contrast to capitalist society, individual labour no longer exists in an indirect fashion but directly as a component part of total labour” (emphasis altered). As I have discussed elsewhere, this statement was centrally important to Marx’s analysis in that work of the differences between capitalism and communism.

There is a shade of difference between “directly general” and “directly social.” The “directly general” formulation bears the mark of its provenance, the process by which Marx arrives at the concept in his critique of Darimon. He derives the fact that labor in commodity-producing societies is not directly general from the fact that the commodities themselves are not—only money is directly general (pp. 168-169, 171; cf. p. 146, p. 150). But in the “directly social” formulation, the concept stands on its own. The directly or indirectly social character of labor is no longer just a conclusion deduced from an investigation of money; it is able to serve as a starting point for further theorizing.

This is a classic instance of the relation between abstractions and concreta that Marx discussed in the Grundrisse’s introduction (p. 101):

The concrete … appears in the process of thinking … as a result, not as a point of departure, even though it is the point of departure in reality and hence also the point of departure for observation and conception. … the method of rising from the abstract to the concrete is only the way in which thought appropriates the concrete, reproduces it as the concrete in the mind. But this is by no means the process by which the concrete itself comes into being.

The indirectly social character of labor in commodity-producing societies does not come into being as a result of money or exchange, even though it was conceptually derived from them. In reality, the indirect sociality of labor is “the point of departure.”

But “in the process of thinking”—that is, in the critique of Darimon—the concept emerges as a result of an inquiry into money. Marx has just concluded that the central bank in a “labor money” system would actually have to perform functions that are incompatible with a system of commodity exchange among individuals. The bank would have to be either “a despotic ruler of production and trustee of distribution” or merely the accounting agency of “a society producing in common” (pp. 155-156). This conclusion immediately leads him into a discussion of different kinds of society—in particular, their relations of domination and subordination (“dependence”):

Relations of personal dependence … are the first social forms …. Personal independence founded on objective dependence is the second great form …. Free individuality, based on the universal development of individuals and on their subordination of their communal, social productivity [sic; production?] as their social wealth, is the third stage. [p. 158]

“Relations of personal dependence” refers to relations in precapitalist societies such as dependence of slaves on masters and serfs on landlords. Capitalist societies eliminate such dependence but replace it with “objective dependence”—relations in which persons are controlled by and subordinate to things. “The individual carries his social power … in his pocket” (p. 157). The thing, the money in the pocket, is what has the social power; the individual has power only through it. Labor and products “appear as something alien and objective, confronting the individuals, not as their relation to one another, but as their subordination to relations which subsist independently of them” (ibid.). “In exchange value, the social connection between persons is transformed into a social relation between things” (ibid.). These ideas will later reappear in the “fetishism of the commodity” section in the first chapter of Capital, volume 1—both the concept of a social relation between things and the three successive forms of society.[11]

Shortly thereafter, Marx says that, in commodity-producing society, “individuals now produce only for society and in society,” yet “production is not directly social, is not ‘the offspring of association’” (p. 158). He seems to be moving toward an articulation of the concept of indirectly social labor. But he quickly moves away. In the next nine pages, he returns to his more general exploration of “objective dependence” despite “personal independence,” focusing on money and exchange. He seems unsure of where to go next.

Then, in a paragraph that begins with a discussion of why commodities are exchangeable with money (p. 167), Marx segues into a discussion of labor. He mentions that the rate at which a commodity exchanges with money is “determined by the amount of labour time objectified in the commodity.” He then notes that “Adam Smith says that labour (labour time) is the original money with which all commodities are purchased” (ibid.)[12] (Smith’s references to purchase and money are metaphorical. His point is that the production of something costs workers their labor; labor is what they give up in order to produce it.) Shortly thereafter, Marx recalls that Smith also wrote that the worker has to produce not only “a particular product” but also “a quantity of the general commodity” (p. 169, emphases added).[13] (This is a very “creative” reading since, as Marx himself notes, Smith was not referring to one act of labor performing two functions. He was referring to one part of what workers produce being produced for their own consumption, while the other part is produced for sale in the market.)

After making some incidental remarks, Marx combines the two points he has gotten from Smith: a worker’s labor needs to be not only a particular “money” but also a general “money.” But it is not general—not directly. “The labour of the individual … is the money with which he directly buys the product, the object of his particular activity; but it is a particular money, which buys precisely only this specific product. In order to be general money directly, it would have to be not a particular, but general labour from the outset” (p. 171).

But in commodity-producing society, labor is not general from the outset, not directly general. “Those who want to make the labour of the individual directly into money (i.e. his product as well), into realized exchange value”—Bray, Gray, Proudhon, Darimon, and so forth,

want therefore to determine that labour directly as general labour, i.e. to negate precisely the conditions under which it must be made into money and exchange values …. Labour on the basis of exchange values presupposes, precisely, that neither the labour of the individual nor his product are directly general …. [p. 172]

What Marx has done here, assisted by Smith’s analogy between labor and money, is to take the contradiction between commodities and money, and work out an analogous contradiction between particular and general labor. Money is generally exchangeable, exchangeable with all other commodities, but these other commodities’ exchangeability is particular; they are exchangeable only with money, not one another. And in the exchange relation, money alone seems to have the general property of being a thing of value, while other commodities seem to be merely particular things that become valuable only by being exchangeable with money. Thus, money is directly general, while other commodities are general only indirectly, through the mediation of money. Marx is saying that the properties of the products of labor are also the properties of labor itself. In a commodity-producing society, the labor that produces a particular product is not directly general. To become general, an act of labor must also produce a product that is exchangeable with money. Thus the labor, like its product, becomes general only indirectly, through the mediation of money.

While making this argument, Marx situates it in the context of his earlier discussion of the three successive forms of society. He contrasts the character of labor in commodity-producing society to its character in “a society producing in common” in which “free individuality” prevails. In the latter society, “[t]he communal character of production would make the product into a communal, general product from the outset” (p. 171). And what would hold true for the product would also hold true for the labor that produces it. “[L]abour [would be] posited as general … before exchange; i.e. the exchange of products would in no way be the medium by which the participation of the individual in general production is mediated” (ibid.). And since, in this case, “[t]he labour of the individual is posited from the outset as social labour[, … he] has no particular product to exchange. His product is not an exchange value. The product does not first have to be transposed into a particular form [i.e., change places with money] in order to attain a general character for the individual” (p. 172).

In other words, in a society that produces communally, the producers’ labor and the products they produce are social from the outset. This implies that the producers do not exchange products with one another, that the products are not (exchange) values, and that there is no money for which products exchange. Conversely, the existence of money implies that the products are (exchange) values, that the producers exchange them, and that production is not communal—the products and the producers’ labor are not social from the outset. Indirect sociality of labor is the relation of production that is made manifest in the form of money.

7. Conclusion: Two Kinds of “Realistic Outlook”

In Section 4, I argued that Marx’s critiques of Proudhonism and similar radical tendencies were principally about what is economically possible and what is not. Turning specifically to Marx’s critique of Darimon, Sections 5 and 6 showed how its discussion of labor money as well as the discussion of directly and indirectly social labor are bound up with the issue of possibility and impossibility. Because money must be directly social, but labor in commodity-producing society is not, labor cannot function as money.

As I mentioned in Section 4, the issue of possibility and impossibility became an immediate political issue for Marx in 1875, when two German socialist parties were about to unite on the basis of the Gotha Program. The Program called for “fair distribution” without calling for changes in society’s relations of production, but Marx argued that the former requires the latter. If relations of production do not undergo revolutionary transformation, the desired distributional change is not possible. Largely for this reason, he opposed the Program and the unification based on it, charging that the Program “pervert[ed] the realistic outlook, which it cost so much effort to instill into the Party.”

What Marx meant by “realistic outlook” here is the realism of basing action on what is possible, pursuing one’s goal by employing means that can actually achieve it. Yet there also exists, of course, a very different kind of political realism, the realism of doing what seems politically advantageous.

In Marx’s time, and since, it is the latter kind of realism that a wide swath of the radical movement has found appealing. His ability to persuade others to base their political commitments on what is and isn’t possible thus proved to be very limited, even when they “agreed” with his ideas. At the congress in Gotha, the unification of Ferdinand Lassalle’s party and the “Marxist” party went through. Marxists in the period of the Second International treated Lassalle and Marx as equal co-founders of their parties. And while the influence of Proudhonism within French socialism waned from the late 1860s onward, it waned because Proudhon’s political positions, such as opposition to strikes, came into conflict with the political demands of France’s working class, which had since become a largely industrial class. Marx’s arguments, especially his theoretical arguments about economic matters, had little if any effect.

Nonetheless, I submit, we have a duty to seek and speak the truth, and getting things right is its own reward. It is also practically important. While doing what seems politically advantageous may succeed in “building the left” and even in bringing down the existing society, getting things right is imperative if the goal is ultimately to create a new one. And ferment from below can cause prior judgments about what succeeds politically to become passé. Owing to objective events—the Paris Commune and the Bolshevik Revolution, above all—Marx eventually became a household name while Proudhon and Darimon have not.

Appendix: Outline of Marx’s Critique of Darimon

p. 115. Quote from the start of Darimon’s book that blames the monetary crisis of the time on the metallic standard.

pp. 115-119. (From Begins with the measures … to … the genesis of their theoretical abstractions.) Analysis and critique of Darimon’s data on fluctuations in the asset portfolio of the Bank of France. Darimon construed the data as evidence that France’s bimetallic standard was in conflict with “the requirements of circulation,” that is, the issuance of enough money to serve as a medium of exchange. Specifically, he argued that the Bank’s ability to lend was constrained by the amount of metal assets it held. Marx shows, however, that Darimon misunderstood and misused the data, largely because he conflated money and credit and therefore thought that their movements were rigidly correlated. In fact, however, “[t]he quantity of discounted bills and the fluctuations in this quantity express the requirements of credit, whereas the quantity of money in circulation is determined by quite different influences.”[14]

pp. 119-122. (From Let us pursue Darimon further to … the product of modern commerce and modern industry?) Discussion of why the Bank of France raised its discount rate at a moment of crisis, when borrowers instead needed easier credit conditions.[15] Darimon claimed that France’s bimetallic standard was to blame; its reserves of metal were being depleted. Marx responded that the Bank’s behavior was just how markets operate. Suppliers raise the price of their services when demand for them increases. “And the bank should be made an exception to these general economic laws?” Marx also argues that Darimon was either suggesting that the Bank did not need to hoard metal reserves, which overlooks the fact that they were needed to settle international transactions, or he was complaining that the Bank hoarded more metal than was necessary, in which case he was just engaged in a standard policy dispute among the bourgeoise.

pp. 122-123. (From We have here reached the fundamental question … to … we shall pay close attention.) Paragraph on “the fundamental question,” which “Proudhon and his associates never even raise … in its pure form.” The question is about whether—if capitalist relations of production continue to exist—any kind of monetary system, including a labor-money system, can achieve the goals sought by proponents of monetary reform.

pp. 123-124. (From This much is evident … to … are convertible or inconvertible.) Reiteration of two points: that monetary turnover (circulation) and credit are different; and that Darimon was wrong to blame the bimetallic standard for the rise in the Bank of France’s discount rate. Includes parenthetical remark that the “free credit” the Proudhonists were now calling for is a euphemistic reformulation of Proudhon’s original slogan, “Property is theft.”

pp. 124-125. (From The behaviour of the Bank of France … to … Darimon’s theory of crises later.) Discussion of Darimon’s account of public debate regarding the Bank of France’s current monetary policy. Against Darimon, Marx argues that central banks are not able to “regulate credit” (control the volume of credit in existence) except during crises, when their power is “extraordinarily limited.” If private bankers are offering to discount bills of exchange at a lower rate than the central bank charges, it is unable to discount bills at all, and thus unable to affect the volume of credit.

pp. 125-126. (From In the chapter “Short History … to This by the way.) Marx challenges Darimon’s claim that monetary crises are caused exclusively by the metallic standard, noting that his history of the topic omits the monetary crises in England of 1809 and 1811, which occurred even though Britain’s central bank was issuing inconvertible notes (i.e., notes that were not guaranteed to be exchangeable for gold at a fixed rate.)

pp. 126-127. (From Gold and silver are commodities … to … once its exclusiveness is gone.) Paragraph on Darimon’s proposal to abolish the privileged role of gold and silver. Marx notes that this proposal is tantamount to “making every commodity money.” However, the “bourgeois system of exchange itself necessitate[s] a specific instrument of exchange”—one specific asset, set apart from the rest. To highlight the “nonsensicality” and “impossibility” of Darimon’s proposal, he compares it to the slogan, “Let the pope remain, but make everybody pope.”

pp. 127-131. (From The bullion drains do … to … quantity of gold at the bank.) On causes of monetary crises associated with bullion drains (central banks’ export of precious metals, to settle international transactions).[16] Marx challenges Darimon’s view that such monetary crises would be eliminated if the metallic standard were abandoned. He argues that the causes of these crises are what economists call “real” (non-monetary) factors. Events within a country that produce crises in its “real” economy—war, crop failure, excessive imports, and so on—result, at the same time, in a shortage of money to serve as the medium of exchange. Examining the case of grain-crop failure in detail, Marx concludes that it would produce a crisis “[w]ith or without metallic money, or money of any other kind,” even “if no gold whatever were exported and no grain imported.”

Marx acknowledges that central banks’ actions to prevent bullion drains can “aggravate” monetary crises, but he denies that abandonment of the metallic standard would necessarily solve the problem. If the international gold standard continues to exist—that is, if “foreign nations will accept capital only in the form of gold”—then central banks would still need to hold sufficient volumes of gold reserves.

pp. 131-134. (From There can be hardly a doubt … to … by founding a rational “money system.”) Lengthy paragraph on the convertibility or inconvertibility of paper currency, and on depreciation (or appreciation) of money.

pp. 131-133. (From There can be hardly a doubt … to … the illusions of the circulation artists.) Marx begins with a digression concerning paper currency that is denominated in gold or silver, but not legally convertible into them.[17] Marx argues that such currency is nonetheless economically convertible, convertible in fact, if the amount of gold or silver it can buy in the open market equals its face value. If, however, the paper currency can buy only a smaller amount of gold or silver, then it depreciates. (Marx is evidently suggesting here that it buys not only less gold or silver than its face value, but proportionately smaller amounts of goods, services, and assets generally.)

pp. 133-134. (From Gold or silver money (except where coins … to … by founding a rational “money system.”) The discussion of depreciating currency leads Marx back to Darimon and the subject under discussion (and toward an examination of labor money). He observes that all money—including gold and silver—can and does depreciate and appreciate, in the sense that a unit of money buys smaller or greater amounts of other things at different times. “Darimon and consorts see only the one aspect which surfaces during crises: the appreciation of gold and silver in relation to nearly all other commodities” (i.e., prices of commodities fall). This one-sided perspective is the source of their call to abolish the privileged status of precious metals.

Yet, Marx observes, crises are invariably preceded by “periods of so-called prosperity,” in which gold and silver depreciate (i.e., prices of commodities rise), so Darimon and consorts should also want to “abolish the privileges of commodities in relation to money.” Marx’s point is that booms lead to busts, and thus that rising prices lead to falling prices, so complaints about the privileged status of precious metals reduce to complaints that prices fluctuate. He then says that the way to solve the problem of fluctuating prices is clearly to “abolish prices.” But that requires “doing away with exchange value,” which in turn requires “revolutioniz[ing] bourgeois society economically.” The “evil of bourgeois society” cannot be eliminated simply by reforming the banking system or establishing a rational monetary system.[18]

pp. 134-146. (From Convertibility, therefore—legal or not … to … the social relations which rest on the latter.) Start of a lengthy consideration of “labor money,” which Marx also calls “time-chits.”

pp. 134-136. (From Convertibility, therefore—legal or not … to … the time-chit and hourly productivity.) Marx explains the concept of labor money, and then discusses whether a labor-money system would eliminate the fluctuations in commodities’ prices relative to their values, as proponents of such systems promise. He shows that the fluctuations would persist. Increases in productivity would cause prices to rise in relation to value as measured by gold labor money (i.e., gold money with a face value denominated in units of labor-time) and fall in relation to value as measured by paper labor money.

pp. 136-140. (From The point to be examined here … to … conditioned by their real difference.) Discussion of the (in)convertibility of paper money. Marx reduces the issue of fluctuating prices to differences between value and price—both the nominal difference between them and the real difference. He argues that the “first basic illusion of the time-chitters” is the belief that, by eliminating the nominal difference (i.e., by having labor-time serve as money) they would also eliminate “all crises, all faults of bourgeois production.” Marx rejects that conclusion, arguing that these “faults” are consequences of the real (quantitative) difference between value and price, which would re-emerge in a labor-money system, in the form of a contradiction between actual labor-time and the average labor-time that serves as the standard of value. In other words, the amount of labor-time currently required to produce a commodity (actual labor-time) would not equal the amount of labor-time that a time-chit represents (average labor-time).

pp. 139-146. (From The constant depreciation of commodities … to … the social relations which rest on the latter.) Marx concludes from the preceding discussion that labor money is untenable. One amount of labor-time would equal a different amount of labor time! Since that is impossible, commodities’ values must instead be “measured as prices on a different standard from their own.” This implies, he argues further, that a commodity’s price must be measured in terms of something external to it (not in terms of the labor-time contained in it)—an equivalent. Moreover, one specific instrument, a “universal equivalent,” is ultimately required to measure prices adequately. Since one of the main functions of money is to serve as the universal equivalent, Marx concludes that it is “impossible to abolish money itself as long as exchange value remains the social form of products.”

pp. 146-151. (From The properties of money as (1) measure … to … commodity, exchange value; exchange value, money.) Marx briefly comments on the properties of money, and on money as a power alien to the producers. He then discusses four contradictions “inherent” in the fact that money is distinct from all other commodities. However, in opposition to Darimon and other monetary reformers, who portray money as the cause and the contradictions as the effect, Marx contends that “[m]oney does not create these antitheses and contradictions; it is, rather, the development of these contradictions and antitheses which creates the seemingly transcendental power of money.”

The first contradiction is that it is always possible that a certain commodity cannot be exchanged for money (i.e., sold). Second, under monetary exchange (in contrast to barter), purchase and sale become separate acts, so “their immediate identity ceases.” (E.g., a wholesaler who purchases a commodity might not be able to resell it.) Marx briefly alludes to continual disequilibrium between supply and demand. Third, commerce (wholesale and retail trade) becomes an “independent function,” i.e., an industry distinct from commodity-producing industries. This separation makes commercial crises possible. Fourth, money exists in the form of one particular commodity, which conflicts with money’s universal functions (universal equivalent, etc.), giving rise to additional contradictions. (It is not clear from Marx’s brief discussion what these additional contradictions are, but his reference to “different kinds of money” suggests that he may have been thinking of economic disruptions caused by changes in the relative values of different currencies, changes in the relative values of gold and silver, etc.)

pp. 151-153. (From (Economist. 24 January 1857. to (Economist. 24 January 1857.)) Quotations and summaries of material recently published in the Economist and the Morning Star, on banks and monetary policy. In between them, one sentence refers back to the preceding discussion and anticipates the structure and main thesis of the “value-form” section in the first chapter of Capital, vol. 1: “All contradictions of the monetary system and of the exchange of products under the monetary system are the development of the relation of products as exchange values, of their definition as exchange value or as value pure and simple.”

pp. 153-156. (From Now, it might be thought that … to … into the papacy of production.) Marx resumes his consideration of labor money. He first briefly reiterates that key assumptions underlying labor-money proposals—that labor money would ensure that price equals value and that supply equals demand—are unwarranted, since they conflict with “the real relations of money.” He then discusses the role of the central bank in the labor-money system proposed by John Gray. He concludes that, for the system to work, the bank would have to be either “the general buyer and seller[,] the general producer[, … and] a despotic ruler of production and trustee of distribution” or merely “a board which keeps the books and accounts for a society producing in common.”

pp. 156-165. (From The dissolution of all products and activities … to … purely out of relations of production and exchange.) Marx’s reference to how the bank’s role would differ in these two different kinds of society now leads him to situate commodity exchange and money within a broader context—the historical development of relations of dependence and independence. This discussion anticipates key aspects of the section on the “fetishism of the commodity” in the first chapter of Capital, vol. 1.

Marx divides social relations into three successive stages of development: relations of “[p]ersonal dependence” (e.g., dependence of slaves on masters); relations of “[p]ersonal independence founded on objective dependence”; and “[f]ree individuality,” along with communal “productivity” (production?) that is subordinate to individuals’ development. Exchange and monetary relations are crucial elements of the second stage, in which “the social connection between persons is transformed into a social relation between things.” An individual’s “social power, as well as his bond with society” consists in his ownership “of exchange values, of money.” This is an “alien and objective” social connection, independent of individuals, to which they are subordinate. Although “individuals now produce only for society and in society[, …] production is not directly social, is not ‘the offspring of association.’”

pp. 165-167. (From The product becomes a commodity. to … take its denomination from the specific commodity.) Discussion of the historical development of money, in relation to the historical development of exchange relations.

pp. 167-173. (From It is because the commodity is exchange value … to … the equivalence, the identity of their quality.) Marx returns to—and ties together—the issues of labor money, directly and indirectly social labor, and individuals’ objective dependence despite their personal independence. (He also makes some incidental remarks.)

pp. 167-169. (From It is because the commodity is exchange value … to … money which is distinct from labour time.) A commodity’s value is “determined by the amount of labour time objectified” in it, but the money that expresses the commodity’s value must be distinct from it, and from all other commodities. Hence, “the quantity of labour time [that is objectified] must not be expressed in its immediate, particular product, but in a mediated, general product” (money). It follows that “[l]abour time cannot directly be money (a demand which is the same … as demanding that every commodity should simply be its own money).”

p. 169. (From In Adam Smith this contradiction still appears … to … not yet fully developed on a national scale.) Paragraph drawing out a further implication of the difference between labor-time and money: the dual character of workers’ labor. They have to produce not only a “particular product” but also “a quantity of the general commodity,” money. (Or, in terms Marx will later employ, they have to produce not only a use-value but value as well.)

pp. 169-170. (From (Incidental remark: … to … value as an instrument of circulation is affected.)) Incidental remarks on gold and silver, not closely related to the main topic at this point.

pp. 171-172. (From Labour time itself exists … to … a form of money distinct from itself.) Further development of the concepts of directly and indirectly social labor. “On the basis of exchange values, labour is posited as general only through exchange.” Thus, “neither the labour of the individual nor his product are directly general; … the product attains this form only by passing through an objective mediation by means of a form of money distinct from itself.” In contrast, when production is communal, exchange of products is no longer “the medium by which the participation of the individual in general production is mediated.” “The labour of the individual is posited from the outset as social labour,” and the product produced by that labor is “a communal, general product from the outset.”

Marx draws the conclusion that proponents of labor money in effect want individuals’ labor to “directly [be] general labour,” instead of first having to “be made into money and exchange values.” But “[t]his demand can be satisfied only under conditions where it can no longer be raised.” In other words, it can be satisfied only when money and exchange of products no longer exist, because production is communal.

pp. 172-173. (From On the basis of communal production … to … the equivalence, the identity of their quality.) Marx states that, in a society with “communal production,” the “determination of time” (i.e., determining the amounts of labor-time needed to produce different things), and economizing on and efficiently allocating (labor-)time, will remain essential. However, “this is essentially different from a measurement of exchange values (labour or products) by labour time.”

Endnotes

[1] The full title of Proudhon’s book is Système des contradictions économiques, ou Philosophie de la misère (The System of Economic Contradictions, or the Philosophy of Poverty).

[2] That Capital is a critique, not only of bourgeois political economy and capitalism, but of Proudhonism as well, has typically been underappreciated. William Clare Roberts’ Marx’s Inferno is an exception.

[3] The quote is from Robert Graham, “The General Idea of Proudhon’s Revolution.”

[4] Wood was aware of the facts cited in this paragraph as well. My account is largely based on pp. 45-46 of her thesis.

[5] The page numbers of my citations of the Grundrisse are those of the (identically paginated) Penguin Books and Vintage Books editions, translated by Martin Nicolaus. His translation is available online, without page numbers, at the Marxists Internet Archive.

[6] Most countries on a metallic standard had a gold standard, in which paper currency was legally “convertible” into gold. That is, central banks guaranteed that they would accept paper currency in exchange for gold, at a fixed, prespecified rate. However, France had a bimetallic standard; paper currency was convertible into both gold and silver, and the legal rate of exchange of gold for silver was fixed. A liquidity crisis is a widespread shortage of cash to make purchases and pay debts—insufficient income or wealth that exists in the form of money (not insufficient income or wealth as such).

[7] Prior to writing Capital, Marx failed to distinguish clearly between value (wealth in the abstract, the property that all commodities share) and exchange-value (the form of appearance of value, i.e., the amount of some other thing—either money or something else—for which a commodity can be exchanged). What he means by “exchange value” here is the former (for further discussion, see my essay, “Marx’s Development of the Concept of Intrinsic Value”). The “social form of products” he refers to is the commodity form; as commodities, the products are not only useful things, but also things that have value.