by Andrew Kliman

Editor’s note: This article will be published in the December 2022 special issue of the Journal of Global Faultlines (vol. 9, no. 2, Dec. 2022). We thank the editors for graciously allowing us to pre-publish it here.

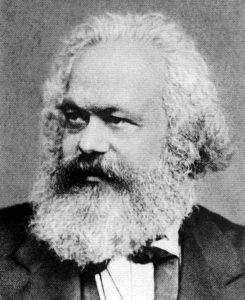

For online translations of works by Karl Marx and V. I. Lenin quoted in the article––which differ from the translations from which the article quotes––see Marx’s Capital, vol. 1, Capital, vol. 3, Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, and Critique of the Gotha Programme, and Lenin’s The State and Revolution.

Abstract

Karl Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program is largely about the differences between capitalism and communism, and the changes that will be needed to effect a revolutionary transformation of capitalism into communism. Because the author believes that these aspects of the Critique are still not widely understood or internalized, the paper undertakes a close reading of them. The reading is informed by Marx’s conception of the relation between a society’s economic basis and its political and legal superstructure, and it calls attention to ways in which his critique draws on his concepts of directly and indirectly social labor and his value theory.

An Analysis and Commentary

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life.

––Karl Marx, Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy[1]

Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development which this determines.

––Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Programme[2]

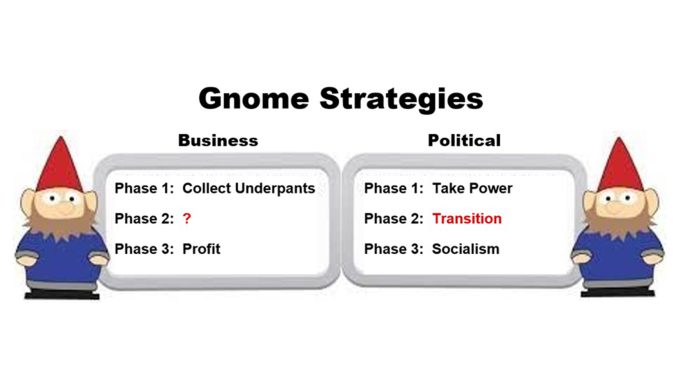

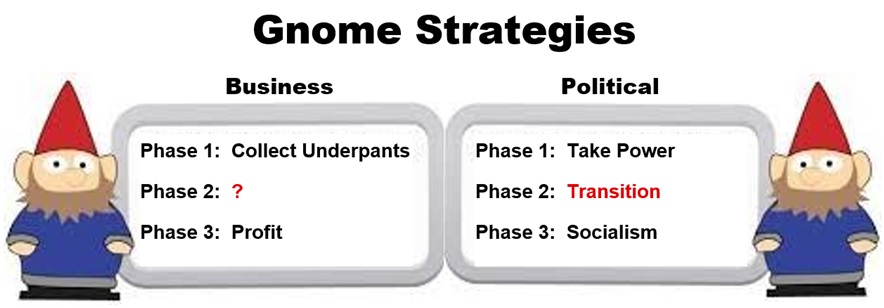

Much, if not most, Marxism after Marx has rested on a glaring contradiction. On the one hand, it apparently endorses the ideas expressed in the epigraphs above. On the other hand, its conceptions of social transformation, and of the kinds of changes that are needed for social transformation to be viable, are grounded in some version of “political determinism,” the idea that “political changes and/or legal changes are the determining factors in social change” (Kliman, 2013b, 2013a).

The political and legal changes proposed by Marxists (and some non-Marxists) to solve capitalism’s ills include, among others, nationalization of the means of production and/or financial institutions, worker-owned cooperatives or worker self-management, universal basic income, and equality of wages. The idea of first “voting in socialism” or taking power, and only then deciding, through experimentation or other means, what specific changes are needed, has also been popular.

Common to all such versions of political determinism is the idea that “the capitalists control capitalism––not the other way around” (Kliman 2013b). “Who controls?” thus becomes the key issue. On this view, the driving factor behind revolutionary transformation of society is the right people with the right priorities making decisions about what to do, and then implementing those decisions. Transformation of society’s economic structure is a derivative and relatively straightforward matter.

I do not believe any of this, but I have already put forward my arguments, in the articles cited above and elsewhere, and I need not repeat them. And although I strongly endorse the conception, in the epigraphs above, of the relation between a society’s base and its superstructure, I shall not defend that conception here. Instead, I shall utilize it, to explicate and help us understand what Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program (CGP) says about the differences between capitalism and communism and about the changes that will be needed to effect a revolutionary transformation of capitalism into communism. I think the CGP still has much to offer people searching for a viable alternative to capitalism, much that has still not been widely understood or internalized, because it is such a dense and theoretically demanding work.

I believe that, at this moment, I can do more to help work out a viable alternative to capitalism by undertaking a close reading of the CGP’s discussion of capitalism vs. communism than I could do by discussing my own ideas. The space I have been given to present this close reading is generous––yet somehow just barely sufficient!––so this paper does little more than present it. In particular, it generally refrains from comparing my interpretations to other ones.

“Fair Distribution” and “Undiminished Proceeds of Labor”

One major element of the CGP is Marx’s discussion of the differences between capitalism and communism, and of the changes that will be needed to transform the former into the latter. This discussion was part of his response to a clause in the draft Gotha Program’s first paragraph––”the proceeds of labour belong undiminished with equal right to all members of society” (quoted in Marx (1989: 81)––and to its third paragraph, which stated:

The emancipation of labour demands the raising of the means of labor to the common property of society and the collective regulation of the total labour with a fair distribution of the proceeds of labour [quoted in Marx, 1989: 83]

Marx (1989: 83) understood the third paragraph to be referring to a communist society, since “the means of labour are common property and the total labour is collectively regulated.” And reading the two paragraphs together, he concluded that the draft Program was implying that a “fair distribution of the proceeds of labour” in communist society is one in which “the proceeds of labour belong undiminished with equal right to all members of society.”

Marx was extremely critical of the call for “fair distribution.” His discussion of the transformation of capitalism into communism emerged within his critique of that phrase. He began by asking, rhetorically,

What is ‘fair distribution’?

Do not the bourgeois assert that present-day distribution is ‘fair’? And is it not, in fact, the only ‘fair’ distribution on the basis of the present-day mode of production? Are economic relations regulated by legal conceptions or do not, on the contrary, legal relations arise from economic ones? Have not also the socialist sectarians the most varied notions about ‘fair’ distribution? [Marx, 1989: 84]

Although Marx phrased these criticisms in the form of questions, it should be clear that he was affirming that “present-day distribution” is indeed “the only ‘fair’ distribution on the basis of the present-day mode of production.” As we shall see, this conclusion becomes even clearer by the end of his discussion of capitalism vs. communism.

Marx also took issue with what the draft Gotha Program said about “proceeds of labour.” He argued that the term is ambiguous; he questioned whether the draft Program was suggesting that “those who do not work” will have an equal right to the proceeds in a communist society;[3] and he noted that the proceeds of labor available for individual consumption can never be “undiminished.” They must always be less than the total product, even in a communist society, since some of the product must be invested, used to fund government administration and social services, and so on (Marx, 1989: 84–85). He also argued that the very concept of “proceeds of labour” is inapplicable to communist society. “Just as the phrase of the ‘undiminished’ proceeds of labour has disappeared, so now does the phrase of the ‘proceeds of labour’ disappear altogether” (Marx, 1989: 85).

Relations of Production and Relations of Distribution: a Base/Superstructure Relation

In his criticisms (in the form of questions) of the notion of “fair distribution,” Marx reaffirmed his view of the relation between the basis and the superstructure of society, and he applied it to the issue at hand. (He continued to do so, in more detail, when he discussed capitalism vs. communism.) He indicated that the mode of production is “the basis” and that “legal relations arise from economic ones.” The ideas here, and even the language, are very similar to those of his 1859 Preface to the Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy: “The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure” (Marx 1987: 263).

What is also noteworthy is where Marx placed relations of distribution within this complex of relations. This is an issue that his 1959 Preface had not addressed. (Chapter 51 of volume 3 of Capital, drafted many years before the 1875 CGP, had done so, but it was not published during Marx’s lifetime.)

The draft Program’s references to “distribution” were references to distribution of means of consumption (consumer goods and services). This is very similar to what we call “income distribution” today. Marx did not include the distribution of means of consumption within the “basis” or “economic structure of society.” On the contrary, the text indicates that it is a “legal relation,” and thus part of the superstructure. It “arise[s] from” the economic structure.

At a later point in the CGP, Marx (1989: 87) contrasted the distribution of means of consumption to “the distribution of the conditions of production[, which] is a feature of the mode of production itself.” The relation between the two kinds of distribution is thus a relation between an aspect of the legal superstructure and an aspect of the economic base. (“Conditions of production” refers to means of production such as land, materials, and machinery, and “distribution of the conditions of production” refers especially to whether and how possession of means of production is divided among social classes.[4])

Closely related to Marx’s view that superstructural relations “arise” from those of the economic basis is his further contention that the former “correspond to” (fit in with, match) the latter. Accordingly, Chapter 51 of Capital, volume 3 (Marx, 1991: 1022–23) repeatedly used terms like “expresses” and “arises from and corresponds to” when characterizing how distribution relations are related to production relations. In the CGP, different terms are used, but the basic idea seems similar if not identical. Marx (1989: 87, 88) wrote that a particular society’s distribution of consumption goods is a “consequence” of, and “results automatically” from, its particular distribution of the conditions of production. He also criticized the draft Program for treating relations of distribution as independent of––rather than dependent upon––the mode of production and, thus, for portraying redistribution as the crux of socialist transformation:

The vulgar socialists … have taken over from the bourgeois economists the consideration and treatment of distribution as independent of the mode of production and hence the presentation of socialism as turning principally on distribution. After the real relation has long been made clear, why retrogress again? [Marx, 1989: 88]

Capitalist vs. Communist Society (Both Phases)

Immediately after suggesting that the concept of “proceeds of labour” is inapplicable in a communist society, and thus “disappear[s] altogether,” Marx (1989: 85, emphasis in original) justified that claim as follows:

Within the collective society based on common ownership of the means of production, the producers do not exchange their products; just as little does the labour employed on the products appear here as the value of these products, as a material quality possessed by them, since now, in contrast to capitalist society, individual labour no longer exists in an indirect fashion but directly as a component part of total labour. The phrase ‘proceeds of labour’, objectionable even today on account of its ambiguity, thus loses all meaning.

(Since the paragraph is about a collective society in which means of production are commonly owned, “the producers do not exchange their products” does not mean that individual producers are self-sufficient. It means that the products are not bought and sold. When he wrote that the labor expended to produce products does not “appear here” as the products’ value, Marx was not suggesting that this is a false appearance. In other words, he was not denying that products have values under capitalism. He was saying that, while products are both use-values (i.e., useful things) and values under commodity production, including capitalism, they will be only use-values under communism, not values as well. Products of labor that are both use-values and values is thus a “form of appearance” of the products––a form they take on, or assume––that is historically specific, not eternal or inevitable.[5])

Marx did not explain further how his conclusion, that “proceeds of labour” has become a meaningless phrase, follows from the points he made in the first sentence of this paragraph. I believe that the most plausible construal of the paragraph––which is plausible because it does make the conclusion follow from the preceding argument––is the following.

Marx understood the draft Program’s call for equal rights to the “proceeds of labour” to be a reference to an exchange relation, in which workers are paid in exchange for supplying something. In one form of commodity-producing society, capitalist society, what workers supply (according to Marx’s theory) is their labor-power, or ability to work. In an imaginary society in which the workers are independent commodity producers rather than proletarians, they would supply labor services or products. Marx was thus arguing that neither kind of exchange relation is applicable to a communist society, because the latter is not a commodity-producing society, and therefore “the producers do not exchange their products.” If one understands the phrase “proceeds of labour” in this manner, and accepts that a communist society is not a commodity-producing society, then the phrase does “lose all meaning” in such a society.

However, the significance of the paragraph extends far beyond the rebuttal it provides to the draft Program’s call for equal rights to the “proceeds of labour.” In the first sentence, Marx specified four different respects in which communist society will differ from capitalist society. The differences are sweeping: there will be common ownership of the means of production; there will be no exchange of products; the products will not be values (i.e., they will not have value); and labor will exist “directly as a component part of total labour” (i.e., it will be “directly social,” a term he used in other works).

The next paragraph of the CGP begins by noting that

What we are dealing with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society, which is thus in every respect, economically, morally and intellectually, still stamped with the birth-marks of the old society from whose womb it emerges. [Marx, 1989: 85, emphases in original]

This might seem to suggest that the four differences between capitalist and communist society that Marx had just specified pertain only to the lower phase of communist society, not the higher phase as well.

However, nothing in the text suggests that the elements of communist society he had singled out will disappear in its higher phase. As we shall see when we come to his discussion of the latter, he referred exclusively to other factors, not the four elements above, in order to distinguish between the two phases. More importantly, the notion that the higher phase would lack one or more of these elements does not make economic sense. After the lower phase of communism had advanced beyond capitalism in these four ways, why would the higher phase revert to what had existed under capitalism? That would be retrogression, not further social advancement. We must therefore conclude that Marx’s discussion of four elements that distinguish communism from capitalism pertains to both phases of the new society.

In light of later claims made about the relationship between the two phases, what is noteworthy is Marx’s contention that all four of these elements pertain to the lower phase of communism, not only to the higher phase. The break from capitalism is complete, at least in these four respects, from the very start of the lower phase of communism, “just as it emerges from capitalist society.”

Three of the four differences are profound changes in the mode of production––workers’ labor is directly rather than indirectly social; although their labor continues to produce use-values, it does not also create value; and the means of production are held in common, which in turn implies that the society is classless. (At a later point in the text, Marx (1989: 86) noted explicitly that, in the lower phase of communism, there are “no class distinctions, because everyone is only a worker like everyone else.”) And the remaining difference––the producers do not exchange their products––is an immediate implication of another profound difference in the mode of production: labor does not produce commodities, “useful things … produced for the purpose of being exchanged, so that their character as values as already to be taken into consideration during production” (Marx, 1990: 166).

Taken together, these changes constitute a revolutionary transformation of the mode of production. Thus, the lower phase of communism, as Marx conceived it, is not a “transitional society” in the sense of a society with a mixed economy or an economy that occupies a position somewhere in between capitalism and communism. It is, as the text says (explicitly and repeatedly), a communist society.[6]

Marx did, of course, write that the lower phase of communism is “in every respect, economically, morally and intellectually, still stamped with the birth-marks of the old society.” He also stated, a few paragraphs later, that “bourgeois right,” “encumbered by a bourgeois limitation” will still exist––in a certain sense––in the lower phase (Marx 1989: 86, emphasis in original). As we shall see, however, what he was referring to in these passages has nothing to do with the four features of communism he had singled out that distinguish it from capitalism, nor do these passages call into question the point that all of these features are already present from the start of communism’s lower phase.

Marx’s Concepts of Directly and Indirectly Social Labor

It will be helpful to clarify the meaning of Marx’s concept of directly social labor, and its opposite, indirectly social labor, before continuing with the CGP’s discussion of the differences between capitalism and communism. Although they are relatively little known and poorly understood, these concepts are quite important for an understanding of the next several paragraphs of the CGP.

The word translated as “directly,” unmittelbar, is also sometimes translated as “immediately.” In this context, “immediately” means “without mediation.” In capitalist society, and under commodity production generally, labor is not immediately social labor. In other words, the labor performed by an individual does not immediately qualify as a contribution to society, an act of social labor. Further mediations are needed to make it an act of social labor; that is, additional conditions must be satisfied. In communist society, however, the labor performed by an individual will directly qualify as social labor. No further mediations will be needed to turn the individual’s labor into social labor; it will qualify as social labor, and thus as a contribution to society, whether or not additional conditions are satisfied.

What additional conditions are relevant in commodity-producing societies but not in (either phase of) communist society? They can be summed up by saying that an individual’s labor qualifies as social labor only if, and only to the extent that, it creates value. This statement takes account of several different things. One is that the producer’s product must be a social use-value, something useful not only to herself, but to others. It cannot be a thing of value if it is not a social use-value. Second, the product must be exchangeable at the currently prevailing price (something that can be exchanged at that price, whether on not it is actually exchanged). Thus, labor that produces products for which there is no demand at the currently prevailing price does not create value and does not qualify as social labor.

Third, an individual’s labor creates value only to the extent that it is socially necessary; any labor expended on the production of a product that exceeds the socially necessary labor expenditure does not create value and does not qualify as social labor. Thus, if a worker has taken nine hours to produce a product, but eight hours is the socially necessary amount of labor currently required to produce this kind of product, only eight hours of her labor qualifies as social labor and only 8/9ths of her labor has created value. But what makes a particular amount of labor-time socially necessary and a greater amount excessive? According to Marx (1990: 129), “Socially necessary labour-time is the labor-time required to produce any use-value under the conditions of production normal for a given society and with the average degree of skill and intensity of labour prevalent in that society.” In short, the amount of labor that is socially necessary to produce a commodity is the average amount required, given average technical conditions.

The CGP’s only explicit reference to indirectly and directly social labor is the one already discussed. It indicates that direct sociality of labor is the basis that allows value and production of value to be eliminated: products of labor are no longer values “since now” labor is directly rather than indirectly social. It says no more than that.

However, I contend that the next several paragraphs of the CGP support the interpretation given above (as do passages in several other of Marx’s works). Specifically, I hope to show that this interpretation of directly and indirectly social labor gives rise to an interpretation of Marx’s ensuing discussion that is plausible and that clarifies aspects of it that would otherwise seem confusing or obscure. (After reviewing these paragraphs of the CGP, I shall defend my interpretation of Marx’s concepts of directly and indirectly social labor against the Stalinist interpretation contained in an article published in an authoritative Russian journal in 1943.)

Apart from the brief mention of the connection between direct sociality of labor and elimination of value, the CGP does not discuss the relation between directly social labor and other elements of communist society that distinguish it from capitalism. However, Marx (1987: 320–23) had discussed this in his Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, when criticizing John Gray’s “labor-money” scheme. Gray had proposed a system in which, instead of selling their products in markets, producers hand them over to the national central bank, after which they withdraw from the bank an amount of products whose cost, in terms of labor, is equal to the amount of labor they expended on the products they produced. This proposed change in the relations of exchange was not accompanied by a proposal to change the relations of production, which Gray evidently regarded as unnecessary (Marx, 1987: 320, starred note).

In Marx’s view, Gray had advocated a self-contradictory and thus unviable combination of social relations: a commodity-producing society in which exchange of commodities has been eliminated. Commodities are produced by “isolated independent” producers. However, Gray’s proposal regarding exchange “presupposes that the labour time contained in commodities is immediately social labour time.” In other words, it presupposes that an hour of labor expended to produce a product immediately qualifies as an hour of social labor. But this in turn “presupposes that it is communal labour time or labour-time of directly associated individuals” (Marx, 1987: 321–22, emphasis in original).

Marx then wrote that, if the things that Gray had unconsciously presupposed––directly social labor, communal production, and directly associated individuals––did exist, then

it would indeed be impossible for a specific commodity, such as gold or silver, to confront other commodities as the incarnation of universal labour [i.e., as money] and exchange value would not be turned into price; but neither would use value be turned into exchange value and the product into a commodity, and thus the very basis of bourgeois production would be abolished.

… labor money is a pseudo-economic term, which denotes the pious wish to get rid of money, and together with money to get rid of exchange value, and with exchange value to get rid of commodities, and with commodities to get rid of the bourgeois mode of production[. This is a fact] which remains concealed in Gray’s work and of which Gray himself was not aware …. [Marx, 1987: 322–23]

This critique of Gray’s proposal suggests that capitalist society, and thus its defects, have a hierarchical structure. The existence of money presupposes commodity exchange, which presupposes that products are values, which presupposes that they are commodities, which presupposes the bourgeois mode of production.[7] To eliminate the ills associated with the apex of the hierarchy (money), as Gray desired, we must “go all the way down,” eliminate the whole hierarchical structure by uprooting its foundation. This requires new relations of production that make labor directly rather than indirectly social, including communal production by directly associated individuals.

Capitalism vs. the Lower Phase of Communism

Let us now return to the text of the CGP. Immediately after noting that “we are dealing with … a communist society … just as it emerges from capitalist society,” Marx made the following remark. It may seem at first to be only about the relations of distribution that will exist in the lower phase of communism, but it is actually about its relations of production as well:

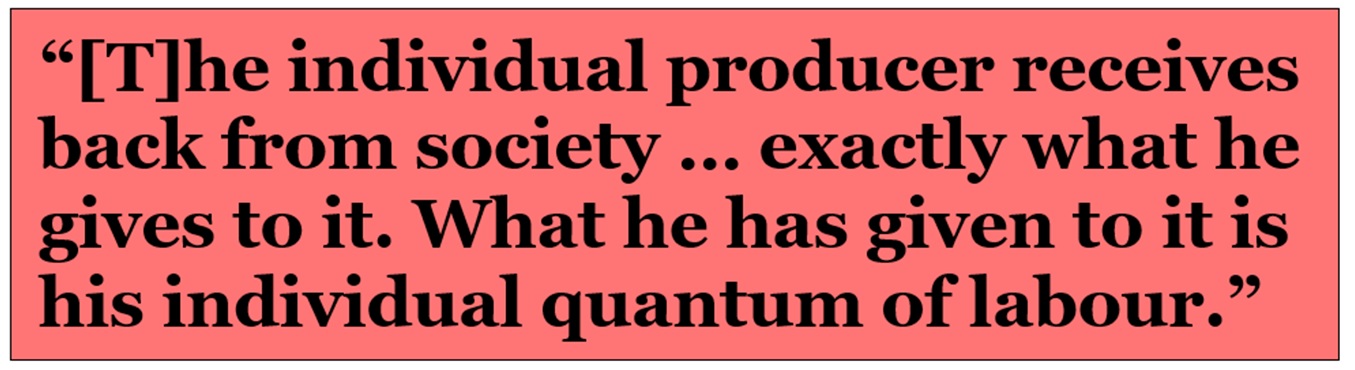

Accordingly, the individual producer receives back from society––after the deductions have been made––exactly what he gives to it. What he has given to it is his individual quantum of labour. For example, the social working day consists of the sum of the individual hours of work; the individual labour time of the individual producer is the part of the social working day contributed by him, his share in it. He receives a certificate from society that he has furnished such and such an amount of labour (after deducting his labor for the common funds), and with this certificate he draws from the social stock of means of consumption as much as the same amount of labour costs. The same amount of labour which he has given to society in one form he receives back in another. [Marx, 1989: 86]

(The two references to “deductions” serve to remind readers about Marx’s criticism of the draft Program’s reference to “undiminished” proceeds of labor.)

The aspect of this paragraph that has received the most attention is its discussion of the relations of distribution. Marx indicated that each producer will receive an amount of means of consumption the cost of which, in terms of labor-time, is equal to the amount of labor-time she or he has worked.

What has received much less attention is what the paragraph, and those that follow it, say about the relations of production and how the relations of distribution correspond to them. Perhaps “what he has given to it is his individual quantum of labour,” and the other instances in which Marx wrote that labor is what the producer gives, or contributes, or furnishes, seem merely to be stating a fact that exists in every kind of society, and thus too obvious and mundane to be worthy of comment.

Yet why did Marx not say that the producer has given to society a product, or a thing of value? Why did he say that the producer has given his “individual quantum of labour” and not “a quantum of socially necessary labour”? In light of Marx’s earlier references to directly social labor and other respects in which production relations of the lower phase of communism will differ from those of capitalism, is the choice of words not significant? I believe that the lack of attention to this issue is a reflection of inadequate understanding of and/or disagreements with Marx’s value theory, his concepts of directly and indirectly social labor, and his view that the elements of society’s superstructure correspond to those of its economic basis.

The next paragraph in the text explains why Marx wrote “individual quantum of labour” rather than something else:

Here obviously the same principle prevails as that which regulates the exchange of commodities, as far as this is the exchange of equal values. Content and form are changed, because under the altered circumstances no one can give anything except his labour, and because, on the other hand, nothing can pass to the ownership of individuals, except individual means of consumption. But, as far as the distribution of the latter among the individual producers is concerned, the same principle prevails …. [Marx, 1989: 86, emphasis added]

Thus, in Marx’s view, the principle that will prevail in the lower phase of communism is not “the same” as the principle that prevails under commodity production in every respect. It is the same only with respect to the relations of distribution. Producers in the new society will receive products whose cost in terms of labor-time is equal to the amounts of labor they perform, just as, in a commodity-producing society, they receive products or money whose value is equal to the amounts of value they have created.[8]

What is not the same are the relations of production––the “altered circumstances”––and thus the “content and form” of the exchange also differ from those that prevail under commodity production. In the lower phase of communism, the individual producer gives to society “his individual quantum of labour” because “no one can give anything except his labour.” No one “gives” either value or products. The producers’ labor no longer contributes value to products (in addition to helping to produce the products themselves), because the products are no longer values (in addition to being use-values). And although the producers continue to supply products in a physical sense, they no longer do so in the relevant social sense. Since the means of production are held in common, the products do not belong to the producers as individuals, so they do not exchange products, and thus “nothing can pass to the ownership of individuals, except individual means of consumption.”

For more than a quarter-century, Marx had excoriated “labor-money” or “time-chit” schemes that Gray, Proudhon, and others had proposed. The goal of these proposals was to institute exchange relations that recognize all individuals’ labor as equal. An hour of labor performed by any individual would qualify as a social contribution equal to that provided by an hour of labor of every other individual. On a superficial reading of the preceding two paragraphs of the CGP, Marx’s discussion of labor certificates is the same proposal he had long excoriated. He seems to be a middle-aged man who tried to counter the Proudhonist and utopian reformers, but came up empty, and has now thrown in the towel.

However, what may look like yet another labor-money scheme rests on an economic foundation that is entirely alien to them. The proposals Marx criticized were intended to institute equal exchange in a society in which labor was only indirectly social and in which production and exchange of values were therefore dominant. In contrast, his discussion of labor certificates pertains to a different kind of society, in which labor is directly social and value relations have therefore been eliminated. In Marx’s view, these differences made his discussion of labor certificates completely different from the proposals he had criticized as unviable.[9] Owing to the revolutionary transformation of the economic foundation, exchange relations that were not viable in a commodity-producing society have become so.

Thus, Marx’s discussion of labor certificates is not really a proposal. Note that he did not use the word “proposal” or any language that would suggest that he was advocating anything or choosing one possibility from among multiple viable ones. His discussion is an analysis of the new relations of distribution that the new mode of production has made possible. And it is the beginning of an argument that the new relations of distribution correspond to the new mode of production––that is, an argument that these relations of distribution, or very similar ones (e.g., electronic accounting of labor expenditures instead of issuance of paper certificates), are the only ones that will be viable in the lower phase of communism.

Unequal Rights for Unequal Quantities of Labor

Marx then discussed producers’ rights to means of consumption in the lower phase of communism, noting both similarities and differences between their rights under capitalism and their rights in the new society. However, this discussion was not exclusively about distribution or rights. Marx related differences pertaining to distribution and rights to the differences between the two societies’ modes of production. He began as follows:

But as far as the distribution of the latter [means of consumption] among the individual producers is concerned, the same principle prevails as in the exchange of commodity- equivalents: a given amount of labour in one form is exchanged for an equal amount of labour in another form.

Hence, equal right here is still in principle––bourgeois right, although principle and practice are no longer at loggerheads, while the exchange of equivalents in commodity exchange exists only on the average and not in the individual case. [Marx 1989: 86, emphases in original]

In the first of these paragraphs, Marx was suggesting that a producer in the lower phase of communism who performs a certain amount of labor, and who obtains from society products that took an equal amount of labor to produce, is in effect, or indirectly, exchanging equal amounts of labor. This is an “exchange” between the individual and the whole of society, not a market exchange between private producers.

The next paragraph introduces an all-important caveat to Marx’s statement that “the same principle prevails as in the exchange of commodity-equivalents”: in a commodity-producing society, the idea that equal quantities of labor are exchanged prevails only in principle, not in actual practice! Principle and practice are at loggerheads because the exchanges that actually take place do not involve equal amounts of labor in any individual case, but “only on the average.” (As we shall see presently, what is at issue here is the difference between the average (socially necessary) amount of labor a commodity contains and the actual amount of labor expended to produce it.) In the lower phase of communism, in contrast, equal amounts of labor are exchanged (in the special sense of “exchange” explained above) in each individual case. Thus “principle and practice are no longer at loggerheads.”

To help clarify what Marx was driving at here, let us assume that commodities of equal value are exchanged––there is no fraud, and factors that cause commodities’ prices to differ from their values either cancel out or are inoperative. Even in this case, the amounts of labor expended on the production of the two commodities will almost always be unequal, because (on Marx’s theory) the magnitudes of the commodities’ values are determined by the average (socially necessary) amounts of labor required to produce them, not by the amounts of labor actually expended to produce these particular items.

For example, if 10 labor-hours is the socially necessary amount of labor needed to produce either 20 yards of linen or 1 coat, then the linen and the coat are of equal value. But 15 hours of labor may actually have been expended to produce a particular 20 yards of linen, if the linen workers are especially feeble or ill-trained, or if they have obsolete equipment, while only 5 hours of labor may actually have been expended to produce a particular coat, if the coat producers are particularly able-bodied, highly trained, or assisted by advanced technology.[10] As Marx repeatedly stressed when opposing the Proudhonist and utopian “labor-money” schemes, this is not an infringement on the “law of value.” It is how the law operates, even in the most “ideal” case in which fraud, price-value differences, and so on are absent.

It is how capitalism must operate. The linen workers under consideration produce only 20 yards of linen in 15 hours, while average linen workers produce 30 yards. If the capitalist system were to “recognize” the former as having created as much value as the latter create, it would be subsidizing and incentivizing technological backwardness and inefficiency. If it did this regularly, throughout the economy, it would soon collapse.

Another implication of the “law of value” is crucial to the issue of distribution. If the 20 yards of linen exchange for 1 coat, the linen workers who worked for 15 hours have not been cheated or exploited by the coat producers who worked for only 5 hours, nor are they victims of unequal exchange. The linen workers receive an amount of value equal to the value of the linen they have given in exchange for the coat, and similarly for the coat producers. To be sure, the linen workers are victims, but what is victimizing them is not the exchange process. They are victims of a society in which one’s contribution to social production depends on and is measured by the number of products one produces and the amount of value one creates, which in turn depend on one’s access to technology, on one’s training and abilities, and on whether one’s product is a social use-value.

Marx was thus suggesting that the lower phase of communism would be different in that, if a worker worked for 15 hours, all of this labor would immediately qualify as social labor––irrespective of the vintage of the equipment with which she worked, irrespective of her particular innate abilities and training, and thus, irrespective of the amounts of products she produced and demand for these products. The value of what she produced would also not matter, of course, since value and the production of value would not exist.

This is a difference, in the first instance, in the relations of production. In particular, it is a difference between directly and indirectly social labor. At issue are what qualifies as a contribution to social production and what the societies produce (only use-values, or values as well). Marx was not making a stand-alone point about distribution––a worker who works for 15 hours will receive products whose labor-time cost is 15 hours––much less a proposal. His point was that this new relation of distribution corresponds to, is made possible by, and is a consequence of the direct sociality of labor and other new relations of production that have enabled communist society to “advance” beyond capitalism.

Marx (1989: 86, emphases in original) then wrote:

In spite of this advance, this equal right is still constantly encumbered by a bourgeois limitation. The right of the producers is proportional to the labour they supply; the equality consists in the fact that measurement is made with an equal standard, labour. But one man is superior to another physically or mentally and so supplies more labour in the same time, or can work for a longer time; and labour, to serve as a measure, must be defined by its duration or intensity, otherwise it ceases to be a standard of measurement. This equal right is an unequal right for unequal labour.

This paragraph is mostly about how the amount of labor contributed will be “measured” or, more precisely, about what will qualify as performance of labor. Marx indicated that the amount of labor performed will depend on its intensity and duration (“supplies more labour in the same time, or can work for a longer time”). “Duration” refers to how long a worker works. “Intensity” refers to how hard or how diligently she works, how much labor she supplies in within a span of time.[11]

To understand the paragraph’s references to labor as an “equal standard,” to “unequal labour,” and to the amount of labor supplied, it is crucial not to confuse intensity with productivity. “Productivity of labor” refers to how much product a unit of labor produces, not to how hard or diligently the worker works.[12] It thus depends greatly on the technology of production, and somewhat on the worker’s skills and training, the availability and quality of raw materials, and other factors. If two workers work equally long and hard, but one has access to the latest technology while the other works with equipment that should have been scrapped long ago, the first worker’s productivity can be tens, or even hundreds, of times as great as the second worker’s.[13]

This paragraph in the CGP therefore does not introduce any qualification to Marx’s earlier statements that the worker gives to society “his individual quantum of labor” and receives in return products of equal cost in terms of labor. It does not stipulate any condition that the worker’s labor must satisfy before it can qualify as social labor. In particular, it does not make the worker’s contribution to social production dependent on how much product he or she produces. A unit of actual labor, not a unit of output or anything else, is the “equal standard” applied universally when assessing the size of the individual’s quantum of labor.

Thus, Marx was indicating that, in the lower phase of communism, there will be equal right for equal quantities of labor (assessed in terms of duration and intensity) that have been contributed to society. The phrase “unequal right for unequal labour” does not contradict this; it is its corollary. Marx was not saying that some acts of labor will be “more equal than others” (to use Orwell’s famous expression) because they produce more products, or value, or anything else. He was simply indicating that some workers will perform more labor than other workers––work longer and/or harder or more diligently. “Unequal labor” refers to these differences in the actual quantities of labor performed and to they alone.

Accordingly, “unequal right for unequal labour” is a “bourgeois limitation” only in the following respects. First, the producer’s right to products will depend on how much labor he or she contributes (although, as discussed above, there will also be social welfare spending to benefit people unable to work, etc.). Marx regarded the very existence of a link between what one contributes and what one receives as a “bourgeois limitation,” though this will become clear only at a later point in the text. Second, this link between how much labor a person contributes and how much labor they receive in return will exist even though the amount of labor they contribute is only partly something they choose freely. It depends in addition on circumstances beyond their control: “one man is superior to another physically or mentally and so supplies more labour in the same time [i.e., works at greater intensity], or can work for a longer time.”

In the remainder of this paragraph, which I have not yet quoted, Marx (1989: 87) elaborated on the same topic and then raised some additional issues:

Besides, one worker is married, another not; one has more children than another, etc., etc. Thus, given an equal amount of work done, and hence an equal share in the social consumption fund, one will in fact receive more than another, one will be richer than another, etc. To avoid all these defects, right would have to be unequal rather than equal.

The additional issues pertain to the fact that household sizes will differ. Thus, if only one member of each household is a worker, and if workers from different households perform equal amounts of work and have equal shares in the social consumption fund, then income per person will be greater in small households and smaller in large ones. Marx regarded the inequalities produced in this way as additional bourgeois limitations or “defects,” even though they would not infringe in any way on the principle of equal right for equal work. Again, what he regarded as defective (without having yet said so) is the link between what one contributes and what one receives.

The Stalinist Revision of the Concepts of Directly and Indirectly Social Labor

In 1943, Pod Znamenem Marksizma, a leading Russian theoretical journal, published an article (unsigned but written principally by the journal’s first-named editor, Stalinist economist L. A. Leontiev) entitled “Some Questions of Teaching Political Economy.”[14] One key claim it made is that the “law of value” operates under “socialism …, i.e., the first phase of communism” ([Leontiev], 1944: 511). This was a revision of prior Russian doctrine and, as we have seen, of Marx’s view as well. But the article appealed to the actual existence of “socialism” in the USSR to decide what does and does not hold true under socialism.

The article also revised the concepts of directly and indirectly labor, in the course of arguing that labor under socialism is directly social even though the “law of value” remains operative. This conceptual revision served to bring the term “directly social labor” into line with the experience of actually-existing “socialism.”

According to the article, two of the three contradictions of commodity-producing society that Marx had identified continue to exist in socialism. Products still have a dual character; they are use-values and values. Accordingly, labor is both concrete and abstract; it produces use-values and also creates value ([Leontiev], 1944: 525). In Marx’s (1990: 148–51) discussion of these contradictions in chapter 1 of Capital, volume 1, what follows immediately from the second contradiction is a third contradiction, between private and social labor. However, the Russian article argued that this third contradiction does not exist under socialism. “The labor of individual workers engaged in socialist enterprises has a direct social character. Every useful expenditure of labor is directly rather than indirectly part of the social labor” ([Leontiev], 1944: 525).

The article’s rationale for this conclusion was that the USSR had abolished the circumstance that labor “finds no social recognition because the commodity it produced remains unsold. … In socialist society, all labor that is useful to society is rewarded by society,” irrespective of sale ([Leontiev], 1944: 525). In other words, if an act of labor does not qualify as social labor unless the product it produces is sold, then it is indirectly social. If it qualifies as social labor irrespective of such a sale, it is directly social.

I am not aware of anywhere where Marx identified sale of the commodity as the intermediary that turns private labor into social labor in a commodity-producing society. He did indicate that indirectly social labor must create value in order to qualify as social labor, that value is expressed in terms of money, and that, to have value, a product of labor must be exchangeable. But products have values and money prices, and they are exchangeable, before and irrespective of whether they are actually sold (i.e., exchanged with money).

The Russian article acknowledged that, in the USSR, the products of labor were values and that their values were expressed as money prices. “In the planned socialist economy of the U.S.S.R., commodities … have prices which are money expressions of their value” ([Leontiev], 1944: 523). Thus, if it had adhered to Marx’s concept of directly social labor, it could not also have affirmed that labor is directly social under “socialism.” Instead, it revised the concept, substituting sale for exchangeability, value, and money.

The article also held that “the measure of labor and measure of consumption in a socialist society can be calculated only on the basis of the law of value” ([Leontiev], 1944: 522), by which it meant that the amounts of labor workers perform and the amounts of consumption goods to which they are entitled are based on the value (and thus the quantity) of the products they produce. It did not try to explain how labor could be directly social when an hour of labor must create a sufficient amount of value in order to qualify as an hour of social labor!

Instead, the article appealed to the experience of actually-existing “socialism”: “it might seem that the simplest way out is to measure labor in hours or days, in what Marx calls the natural measure of labor …. But the difficulty is that the labor of the citizens of a socialist society is not qualitatively uniform.” There are differences between workers and peasants and between mental and manual labor; a variety of skill levels exists; and “one sort of occupation is better equipped technically than another” ([Leontiev], 1944: 522). Hence,

the hour (or day) of work of one worker is not equal to the hour (or day) of another. As a result of this, the measure of labor and measure of consumption in a socialist society can be calculated only on the basis of the law of value. The calculation and comparison of various kinds of labor are not realized directly, by means of the “natural measure of labor”—labor time—but indirectly, by means of accounting and comparison of the products of labor, of commodities. [[Leontiev], 1944: 522, emphases added]

In other words, because one worker’s labor-hour is not equal to another’s, an hour of labor does not qualify directly as an hour of social labor. The amount of social labor a worker performs instead depends upon the quantity and value of the products of his or her labor. Value, expressed in money, is the intermediary that turns an hour of actual labor into some amount of social labor.

This argument clearly implies that, under “socialism,” labor is not directly social in the sense that Marx employed the concept in the CGP (and elsewhere). As we have seen, when he referred to the directly social labor of producers in the lower phase of communism, Marx was referring to the actual amounts of labor they perform, measured in terms of duration and intensity. He held that there will be equal right for equal labor measured thusly. And, of course, he was referring to a society in which value and money do not mediate the relation between an individual producer and society as a whole.

But the article refrained from drawing the obvious conclusion that Russian “socialism” was not actually socialism (i.e., the lower phase of communism). It also refrained from concluding that labor is only indirectly social under “socialism.” Instead, it revised the concepts of directly and indirectly social labor, which served to give its new set of doctrines the semblance of partial continuity with those of Marx.

The Higher Phase of Communism

After completing his analysis of the lower phase of communism, Marx (1989: 87) wrote:

But these defects are inevitable in the first phase of communist society as it is when it has just emerged after prolonged birth pangs from capitalist society. Right [Das Recht: law, rights, justice] can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development which this determines.

In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaving subordination of the individual to the division of labour, and thereby also the antithesis between mental and physical labour, has vanished; after labour has become not only a means of life but life’s prime want; after the productive forces have also increased with the all-round development of the individual, and all the springs of common wealth flow more abundantly––only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs!

I shall take up the first, more general, paragraph later, and address the paragraph about the higher phase of communism now. Marx first drew attention to several respects in which the higher phase depends on further revolutionary transformations of the mode of production, none of which are present, or even possible, at the start of communism’s lower phase. As I noted earlier, the differences in the mode of production that distinguish the lower phase from capitalism persist in the higher phase. The further transformations specified in this paragraph therefore do not replace the communist mode of production of the lower phase with a different one; they are additional differences from what exists under capitalism that improve the communist mode of production and allow it to reach its full potential.

These further transformations are: an end to all divisions of labor, including the division between mental and manual labor; transformation of the nature of work such that it becomes “life’s prime want” instead of a necessary burden; further development of the forces of production, inclusive of both technological development and “all-round” development of individuals and their abilities; and an increase in production. Marx did not specify either the relations among these factors or the degree to which the forces of production must develop and the volume of production must increase.

What he was driving at becomes much clearer, however, when we reflect on his point that the distributive principle of “from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs” can prevail only after the mode of production has been further transformed in these ways. What exactly is the meaning of the distributive principle, when understood in light of this requirement? Why are the further transformations required? And what degree of transformation is required?

In a commodity-producing society, what someone receives in exchange depends on the amounts of value and products they contribute. In the lower phase of communism, the volume of products an individual produces no longer matters, and value production no longer exists, but there is still a link between what one receives and what one contributes. Marx was now envisioning, instead, the achievement of a society in which that link can finally be broken. Everyone will contribute according to their abilities, without regard to what they receive in return, and they will receive in accordance with their needs, without regard to what they have contributed.

This is the literal meaning of the distributive principle in question. In light of the CGP’s preceding analysis––of distribution under capitalism, and especially of “equal right for equal labor” being a bourgeois limitation from which the lower phase of communism suffers––I think this literal reading is the only plausible one.

Gigantic transformations of the mode of production would be needed in order to break the link between what one contributes and what one receives. Before people will be willing to contribute without regard to what they receive, the jobs we do would have to be transformed to the point where work becomes something we want to do rather than something we have to do.[15] Before people can receive without regard to what they contribute, there would have to be genuine abundance, which would require an immense increase in production made possible by an immense development of technology and individuals’ abilities. The elimination of all divisions of labor affects both sides of the non-equation. It is a crucial aspect of the needed transformation of the nature of jobs, and it helps to remove a key obstacle to individuals’ development and thus to the expansion of production.

Once Again on Relations of Production and Relations of Distribution

The immediate reason Marx remarked that “right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development which this determines” is that he wanted to explain why the defects that persist in the lower phase of communism are inevitable. It will have revolutionized the mode of production, such that individuals’ productive contributions now consist of the amounts of work they do, not the amounts of value or products they supply. Yet receipt will still have to be linked to contribution, so it will still not be possible to transcend the principle of equal right for equal labor and the defects to which it leads.

Marx stressed the inevitability of defects in communism’s lower phase because he was displeased that the draft Gotha Program refrained from noting the limited degree to which the relations of production and distribution can be changed immediately. And he stressed that changed relations of distribution require changes in the relations of production because the draft Program ignored that as well. It called for “fair distribution” and so forth in abstraction from such considerations. In Marx’s view, it thereby put forward “obsolete verbal rubbish” and “pervert[ed …] the realistic outlook, which it cost so much effort to instil into the Party” (Marx, 1989: 87).

Yet this remark about the relation between right and society’s economic structure also serves as a fitting culmination of Marx’s whole discussion of the revolutionary transformation of capitalism into communism. It pithily summarizes his concretization of the base/superstructure relation with respect to production and distribution––how they are related in capitalism, in the lower phase of communism, and in its higher phase. In all three cases, rights to the product are only as “high” as society’s economic structure:

▪ The present-day distribution of income corresponds to the present-day mode of production, in which labor is only indirectly social and individuals’ productive contributions therefore depend greatly on the amounts of value they create and the amounts of products they produce. This is fair distribution, given the capitalist mode of production.

▪ Income distribution in the lower phase of communism will be based on the amounts of labor workers perform. This corresponds to that society’s mode of production, in which labor will be directly social but production relations and the limited volume of output will not allow individuals’ rights to society’s output to be decoupled from the amounts of labor they contribute. This is fair distribution, given the degree of development of the communist mode of production in its lower phase.

▪ Income distribution in the higher phase of communism will be based on need, and decoupled from individuals’ productive contributions. This corresponds to the mode of production of the higher phase, since production relations and the greatly expanded volume of output will now make that decoupling feasible. This is fair distribution, given the degree of development of the communist mode of production in its higher phase.

The Political Transition Period

The CGP’s only remaining discussion of the transformation of capitalism into communism, apart from passing remarks, comes near the end. Marx (1989: 95, emphasis in original) wrote,

Between capitalist and communist society lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.

The meaning of this statement has been the subject of considerable controversy.

Some of the controversy seems to stem from Lenin’s (1971: 325ff) substitution of “transition” for “revolutionary transformation” when discussing the period between capitalist and communist society in his The State and Revolution. This substitution, and ambiguous formulations by Lenin, may have encouraged the idea that Marx’s statement refers to a transitional society, not just a political transition period, between capitalism and communism. It may even have encouraged the idea that the lower phase of communist society is not actually a phase of communist society, but a distinct transitional society that exists in between capitalism and communism (or even a non-society; see note 6 above).[16]

Another source of the controversy may be an instinct that, if there is a political transition period and a state associated with it, then there “should” also be a transitional society that goes along with it––but this is a matter of aesthetic preference, not of logic or real-world necessity. Politically motivated willful misinterpretation of Marx’s statement also seems to have added to the controversy.

Finally, much of the controversy stems from failure to recognize that the CGP had argued earlier that, with respect to society’s mode of production, the break from capitalism is complete from the start of the lower phase of communism. Inattention to differences between production relations and distribution relations––and, to put it plainly, inadequate understanding of Marx’s arguments––has often led to misinterpretation of phrases such as “same principle,” “unequal right,” “bourgeois limitation,” and “defects.” As we have seen, these phrases refer to distribution relations in the lower phase of communism, not to its production relations. They do not imply that vestiges of the capitalist mode of production persist. Failure to appreciate this crucial fact has led to the strange conclusion that the lower phase of communism is somehow not a phase of communism! It is misconstrued as something that exists “between capitalist and communist society,” and thus as a phase in which there is still a state that functions as an organ of class domination.

However, this paper has established the fact that the CGP had indeed already argued that a communist society that has just emerged from capitalist society is a communist society. It is not a “transitional society” or one with a mixed economy; its economic structure is fully communist. Given this fact, the controversial sentences become unambiguous and precise, so my commentary on them can be very brief.

(1) The period of revolutionary transformation between capitalist and communist society precedes the latter. (2) It thus precedes the lower phase of communism. The lower phase is part of communist society, not a period of revolutionary transformation nor a subperiod within it. (3) The political transition period and the state associated with it correspond to the period of revolutionary transformation that precedes the communist society. (4) They thus precede the lower phase of that society. They do not continue into it. (5) As we have seen, Marx’s conception of communist society included the idea that it is a classless society, from the very start of its lower phase. This is completely incompatible with a situation in which one class (the proletariat) exercises political power over other classes, much less by means of a state.

I do not see how any other reading of the two sentences is even remotely plausible.

Concluding Comments

Nearly a century and a half have elapsed since Marx wrote the CGP, and we are still nowhere near the point where link between contribution and receipt can be severed. A society in which we contribute according to our abilities if our basic needs are satisfied, and in which our basic needs are satisfied if we make a sufficient contribution, may well be possible in the near term, but Marx’s discussion of the higher phase of communism projected an ultimate goal far more visionary than that. If we want a free, human society in the here and now, we have to think seriously about the whole trajectory of the revolutionary process––not just about the higher phase of communism, but also, and especially, about what transformations of the mode of production will enable society to emerge from capitalism and how they can be achieved.

So, what changes are needed to make labor directly social? I do not know “the answer,” but I am convinced that answers are more likely to be found if we look in the right place rather than the wrong place, and that political determinism is the wrong framework within which to look. Direct sociality of labor cannot be imposed by fiat, passing laws, or “deciding” or “agreeing” that all individuals’ labor immediately qualifies as social labor. Marx noted that direct sociality of labor requires communal production by directly associated individuals, but if this were understood merely as collective ownership and decision-making, it too would remain within the framework of political determinism (and, in any case, necessary conditions differ from sufficient ones).

Lasting changes in the political realm correspond to and arise from changes in the mode of production, not the reverse. If the economic structure of society is such that the purpose of production is to expand wealth in the abstract (i.e., value), then individuals’ labor cannot immediately qualify as social labor––how much wealth is created, and how many products are produced, during different labor-hours must always matter and have consequences. Superstructural changes cannot alter that outcome in the end. What is needed, instead, is to work out how production can have a different purpose and how economic relations can be created in which differences in individuals’ productivity no longer matter and incentives to expand abstract wealth are absent.

References

Conrad, J. (2019) “The Two Phases of Communism,” Weekly Worker, no. 1264, Aug. 18. Available at https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1264/the-two-phases-of-communism/ (accessed June 2022).

Dunayevskaya, R. (1944) “A New Revision of Marxian Economics,” American Economic Review 34(3), 531–37.

Kliman, A. (2013a) “The Incoherence of “Transitional Society,” With Sober Senses, May 5 (text and accompanying video). Available at https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/alternatives-to-capital/video-the-incoherence-of-transitional-society.html (accessed June 2022).

_______ (2013b) “Post-Work: Zombie Social Democracy with a Human Face?,” republished in With Sober Senses, Sept. 13. Available at https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/alternatives-to-capital/post-work-zombie-social-democracy-with-a-human-face.html (accessed June 2022).

Lenin, V. I. (1971) “The State and Revolution,” in V. I. Lenin, Selected Works. New York: International Pub., 264–351.

[Leontiev, L. A., et al.] (1944) “Teaching of Economics in the Soviet Union,” American Economic Review 34(3), 501–30.

Marx, K. (1987) “A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy,” in Karl Marx, Frederick Engels: Collected Works, vol. 29. New York: International Pub., 257–417.

_______ (1989) “Critique of the Gotha Programme,” in Karl Marx, Frederick Engels: Collected Works, vol. 24. New York: International Pub., 75–99.

_______ (1990) Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1. London: Penguin Books.

_______ (1991) Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 3. London: Penguin Books.

Notes

[1] Marx (1987: 263). This passage was written in 1859. Marx (1990: 175–76 n35) quoted much of it, summarized the rest, called it “my view,” and defended it against a critic’s objection in the first chapter of Capital, vol. 1 (both the 1867 first edition and the 1872–73 second edition written shortly before his Critique of the Gotha Program of 1875).

[2] Marx (1989: 88).

[3] Marx was presumably referring to people who refuse to work. Several paragraphs later, he wrote that, in the new society, funds will need to be set aside to provide “for those unable to work” (Marx 1989: 85, emphasis omitted).

[4] As Marx (1989: 87–88) wrote in the same passage, “The capitalist mode of production, for example, rests on the fact that the material conditions of production are in the hands of non-workers in the form of capital and land ownership, while the masses are only owners of the personal condition of production, of labour power.”

[5] Near the end of Chap. 1 of Capital, vol. 1, Marx (1990, pp. 174–175) wrote that political economy “has never once asked the question why that content has assumed that particular form, that is to say, why labour is expressed in value, and why the measurement of labour by its duration is expressed in the magnitude of the value of the product. These formulas … bear the unmistakable stamp of belong to a social formation in which the process of production has mastery over man, instead of the opposite.”

[6] For one example of the claim that Marx’s lower phase of communism is a transitional society, see Conrad (2019). He endorses and quotes from the Draft Programme of the Communist Party of Great Britain, which, he contends, “stands four-square with Marx and Engels.” Conrad’s quotations from that draft program (which, following the practice of Lenin and others, refers to the lower and higher phases of communism as “socialism” and “full communism,” respectively), include the following: “Socialism is not a mode of production. It is the transition from capitalism to communism.” “It begins as capitalism with a workers’ state. … In general socialism is defined as the rule of the working class.” “Classes and social strata exist under socialism …. Social strata will only finally disappear with full communism.” The article does not try to explain how the claims it endorses can be compatible with the passage in which Marx specifies four differences between capitalism and both phases of communism.

[7] Marx’s discussion of “the form of value” in the third section of Chap. 1 of vol. 1 of Capital has a similar hierarchical structure. That discussion was, among other things, a response to proposals by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and his followers that were similar to Gray’s. Marx showed that the contradiction between money and other commodities that the Proudhonists attacked was, at bottom, just a developed form of the contradiction between value and use-value that is present in every commodity.

[8] The analogy works only “as far as” we consider a hypothetical non-exploitative commodity-producing society, one in which the producers “exchange … equal values” (products that are equal in value). In actual capitalist societies, proletarians do not exchange products. On Marx’s theory, they instead exchange their labor-power for wages and benefits, the value of which is less than the amounts of value their labor adds to products.

[9] One of many pieces of textual evidence that supports this conclusion is the following footnote in Chap. 3 of Capital, vol. 1 (Marx, 1990: 88–89 n1): “The question why money does not itself directly represent labour-time, so that a piece of paper may represent, for instance, x hours’ labour, comes down simply to the question why, on the basis of commodity production, the products of labour must take the form of commodities. … It is also asked why private labour cannot be treated as its opposite, directly social labour. I have elsewhere discussed exhaustively the shallow utopianism of the idea of ‘labour-money’ in a society founded on the production of commodities …. I will only say further that [Robert] Owen’s ‘labour money,’ for instance, is no more ‘money’ than a theatre ticket is. Owen presupposes directly socialized labour, a form of production diametrically opposed to the production of commodities. … Owen never made the mistake of presupposing the production of commodities, while, at the same time, by juggling with money, trying to circumvent the necessary conditions of that form of production.”

[10] In this example, I assume that the labor hours expended are of average intensity, i.e., that the individual workers work as hard as workers do on average. Marx’s remark about labor intensity, and its difference from labor productivity, will be discussed below.

[11] Marx (1990: 534) understood the amount of labor performed to be, in effect, the number of hours worked times an index of intensity. The value of the intensity index is 1 if the work is performed at some benchmark level of intensity, 2 if it is performed at double that intensity, etc. The product of hours and this intensity index is the amount of work performed, expressed in terms of hours of benchmark intensity.

[12] I am referring here to what “labor productivity” means, not to how it is estimated. Real-world estimates of labor productivity are typically measures of output per labor-hour, not output per unit of labor.

[13] How can intensity be measured in practice? This is a difficult question. I am not aware of any definitive answer, but it is clear that productivity would be a poor and misleading measure of intensity, for the reasons I have noted. It would result in accurate comparisons of intensity only when the technologies of production are either the same or somehow expressible as multiples of some benchmark technology. Furthermore, when products do not have prices or values, the productivity of workers in different lines of work cannot even be compared, strictly speaking. Who has produced more “stuff” on a given day, workers who produced 10 cars or workers who produced 160 ounces of gold? The question is meaningless.

[14] The article was translated by Raya Dunayevskaya, who later founded the philosophy of Marxist-Humanism. The translated article was published in the American Economic Review, followed by her critique of it (Dunayevskaya, 1944). My critique is indebted to hers.

[15] I cannot “disprove” the idea that changes in “consciousness,” unaccompanied by changes in material conditions that facilitate them, will make people willing to contribute without regard to what they receive. But there is no reason to believe that they can do so, particularly since millions of years of evolution cannot easily be reversed and our survival depends on what we receive.

[16] Lenin himself did not make the errors his substitution may have encouraged. Ambiguities in his text include his occasional use of “socialism” to refer to the lower phase of communism but “communism” to refer to its higher phase, which can encourage the idea that they are not different phases of one society, but two different societies, and a statement that “under communism there remains for a time … even the bourgeois state, without the bourgeoisie!” (Lenin, 1971: 335). This way of describing “an apparatus capable of enforcing the observance of the standards of right” (Lenin, 1971: 335, emphasis in original) proved in retrospect to be too clever by half.

Publication Update: Although the Editor’s note included above indicates that this article will be published in the Journal of Global Faultlines (Vol. 9, No. 2, Dec. 2022), the issue containing this article is now likely not to be published until January 2023. Additional details will be communicated when available.