by Seth Morris

During the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party on July 1, 2021, General Secretary and President (potentially for life) Xi Jinping put on a triumphal display of military marches, televised entertainment, and live public spectacles, capping off the event with a speech from Tiananmen Square. He spoke about China’s glory and strength, reiterating his call for “two centenaries” of Party leadership, and requiring concentrated defense against foreign interests.

Will the masses, the people of the People’s Republic of China, tolerate a century more of the Communist Party dictatorship? Is there a mass basis for the Party’s authority now? To maintain the illusion of Chinese national unity under the Party, Xi did not publicly pose such obvious questions during his dream for the next 100 years. If we want to understand the reality of the Party’s past, present, and future role in China, we have to consider the experiences, ideas, and political activity of the masses of workers, citizens, and colonized subjects over whom the Party assumes complete political authority.

This article aims to accomplish three things:

1) to describe the Chinese Communist Party as it has changed (or not) up to the present Xi Jinping regime,

2) to describe the 2022 mass protests in China (largely in resistance to the “Zero-COVID Policy”), and

3) to interpret, however incompletely, the historical importance of these protests through engaging the work of Raya Dunayevskaya and the broader philosophy of Marxist-Humanism.

To connect these three topics, it helps to first discuss the concept of state-capitalism as defined and developed by Dunayevskaya.

China’s state-capitalist economy and its one-party state have changed in the decades since Dunayevskaya wrote about it,[1] but their capacity for change was limited and shaped by the logic of state-capitalism, which she investigated and found to be the case. I will argue that mass resistance and protest in contemporary China expose the ideological deceptions behind state-capitalist ideology. Although this topic will not be introduced in With Sober Senses for the first time, the history of state-capitalism has defined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), just as the history of the CCP has helped to define state-capitalism.

View of the Forbidden City seen from Tiananmen Square, Beijing. Credit: Markus Winkler on Unsplash, uploaded on August 2020.

State-Capitalism and Party Dictatorship

Since at least the era of Stalin, public propaganda for or against “state socialism” has masked an economic reality uncomfortable for propagandists of either camp: that the USSR, Mao’s China, Castro’s Cuba, Tito’s Yugoslavia, and others have governed capitalist relations of production. The fact that so-called Communist states have been simultaneously capitalist states explains little if it remains an apparent paradox.

In his 1999 essay on the “Changing Role of Workers” in China, Martin K. Whyte wrote, “it is one of the great ironies of our age that something close to a proletarian revolution helped spell the doom not of capitalism, as Marx had predicted, but of state socialism.”[2] This sentiment demonstrates not only a confusion with Marx’s historical materialism (most often a topic for conjecture rather than critical investigation in the bourgeois press[3]), but a confusion with the nature of totalitarian political economy shared especially between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and, formerly, the USSR. The cynical term “state socialism” can be used by Communist Party detractors, for example, who see “real socialism” as the ideology of totalitarian politics, as well as by Communist Party supporters, who see “real socialism” as war against capitalist imperialism.

The theory of state-capitalism emerged during World War II to analyze the new centralizing, industrializing economic regimes within and beyond the Soviet Union, arguing that (1) “the State Plan, the State Party, the monolithic State, differed in no fundamental degree from the capitalism Marx analyzed in Capital, where he showed that it was not the anarchy in the market, but the ‘despotic plan of capital’ which labor confronted in the workplace,” and (2) contemporary history began to show concretely “what Marx could only state in theory about the ultimate development of the concentration and centralization of capital ‘in the hands of a single capitalist or a single capitalist corporation.’”[4]

Raya Dunayevskaya, an originator of the theory, worked for decades to concretize state-capitalism by grounding it in historical evidence, economic analysis and philosophical critique, and by relating Marx’s Humanism to the present and future of workers’ resistance and mass protest against state-capitalism around the world. She wrote that capitalism has everywhere the “same laws of development”: “the compulsion to exploit the masses at home and to carry out wars abroad.” State-capitalism distinguishes itself from private capitalism through its “statification” of industry, not by any purported empowerment of the working class.

Mao admitted the existence of class struggle throughout his rule; the 1963 Manifesto of the Central Committee of the CCP claims that “for decades or even longer after socialist industrialization, … the class struggle continues as an objective law independent of man’s will.”[5] Dunayevskaya pointed out the glaring contradiction between the CCP’s retrogressive theory that “there are classes and class struggles in all socialist countries without exception,” and the view shared by Marx and Lenin (the CCP’s official ideological authorities) that a socialist society must be, by definition, a classless society.

The 1956 National Congress of the PRC declared explicitly that China is “state capitalist.”[6] If the one-party state under Mao was fundamentally state-capitalist, neither market liberalization nor revolution have since overthrown the dictatorship of state-capitalism over “Communist” China. In the Marxist-Humanist analysis of state-capitalism, there is no contradiction (or historical “irony,” contra Whyte) between Marx’s statements on socialist revolution and the actual self-organization of workers against inhumane and alienating class exploitation under capitalism, even when the class that is exploiting those workers calls itself “Marxist,” “Communist,” the “Workers’ Party,” etc. Where Vladimir Lenin fretted over the need for a way out of Russian state-capitalism as it developed out of his own Bolshevik Party before his death, self-described “Marxist-Leninists” the world over have since embraced state-capitalism as the substance and basis of their Orwellian ideologies.

The CCP may be unable to publicly concede its unchallenged fealty to state-capitalism, but it can promote the illusion of political accountability in other ways, especially through singling out issues like corruption. The CCP had already publicly conceded the existence of corruption among its local and national bureaucrats before Xi Jinping assumed power. During the Party’s 18th National Congress (where Xi replaced Hu Jintao as General Secretary), Xi announced a broad “anti-corruption campaign” which, he promised, would bring accountability to corrupt elites (the “tigers”) as well as corrupt low-level bureaucrats (the “flies”). Xi’s new political regime inspired new ideological alignments and sharpened ideological contradictions endemic to the Party, by

- disciplining the Party through Mao-like, strongman power-politics (such as the anti-corruption campaign), but maintaining the reformist’s “capitalist road” to prosperity through international trade;

- replacing the meeker underdog-diplomacy attributable to the Hu Jintao era (roughly 2002-2012) with aggressive military expansionism, while offering little reassurance that the Party can address long-standing domestic problems;

- asserting a vague continuity with Mao’s leadership through the Long March and the founding of the PRC, but also a vague discontinuity with Mao’s leadership during the indescribably disastrous collectivization campaigns and, especially, the Cultural Revolution of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

However much the Party under Xi fears a return to the chaos of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, which purged and publicly executed “establishment” bureaucrats;[7] it seems unlikely that the Chinese people have any interest in a grassroots revival of Maoism,[8] which traumatized and devastated not just the Party bureaucracy, but the masses whom Mao’s state-capitalist dictatorship had used, abused, and massacred.[9]

While Xi today enforces party discipline, implements new technologies for state surveillance of the population and management of industry, violates fundamental human rights of Uyghurs and other nationalities, engages military provocation against Taiwan, and provokes and suppresses domestic protests throughout Mainland China and Hong Kong, the Party has brought about dangers to its sovereignty which it cannot blame on the “tigers” and “flies,” i.e. on bribery and corruption. Whatever internal reforms or practical concessions the Party makes, China’s one-party state is a politically corrupt institution from root to branch. Complicating Xi’s hopes of saving the Party through discipline, political scientist Yuen Yuen Ang argues that bureaucratic corruption has been an underestimated catalyst and facilitator in China’s economic boom, which many inside and outside the Party recognize as the foundation for its long-term political survival. There is of course much more happening “at the top” of Chinese politics, but what has been happening among the masses?

COVID, “Zero-COVID,” and Mass Protest

COVID-19 first appeared in the Wuhan Province of China in December 2019. In the U.S., the pandemic crisis spreading across the globe brought renewed interest in the stability of China’s authoritarian one-party state while it manages an extreme public health crisis. As Chuang Collective reported:

press agencies from the National Review to the New York Times implied that the outbreak may bring a ‘crisis of legitimacy’ to the CCP, despite the fact that there was barely a whiff of an uprising in the air. But the kernel of truth in these predictions lay in their grasp of the economic dimensions of the quarantine … even in China, the epidemic caused the GDP growth rate to slow to an estimated 2 percent in 2020, below its already flagging growth rate of 6 percent in 2019, the lowest in three decades.[10]

Xi’s “anti-corruption” government brought suspicion upon itself when Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist, attempted to warn the public about a new potential SARS outbreak only to have his statements censored and officially condemned. When Li died of COVID-19 a month later, he received a flash of public support (using the social media hashtag #WeWantFreedomOfSpeech) before censors removed posts about his story. The government later recognized Li as an official martyr but could not sweep away public suspicion that the Party’s control over information is not only fallible, but a threat to public health.

Despite practice with similar respiratory illness during the much smaller SARS outbreak of 2002-2004, China’s economic growth has not brought robust and stable welfare institutions under Party management.[11] The weakness of essential public institutions and the failures of political ideology cannot be overcompensated through stronger policing and social coercion, a lesson Xi has been reluctant to learn. Mass protests against the Zero-COVID Policy in 2022 broke through a fundamental lie upheld by the Party and its admirers: the lie that authoritarian capitalism provides an efficient and benign alternative to private property rights, liberal democracy, civil society, human rights, etc. But these protestors, like many before them, broke through the false propaganda that all resistance against state-capitalism (like the “Communism” of the PRC) represents the interests of bourgeois capital and capitalism.

The rest of this article will take a closer look at the recent mass protests and what they mean for the future.

“White Paper” protest at Xidian University. The two characters with paper on them spell Freedom. Credit: Anonymous Wikimedia uploader, uploaded on November 27, 2022.

In 2022, China’s extreme Zero-COVID restrictions received criticism from the World Health Organization for their ineffective implementation and inability to adapt to the changing circumstances of new COVID variants emerging and causing spontaneous outbreaks. For example, when Omicron spread rapidly in Shanghai in early 2022, half of China’s largest city went under strict lockdown for months. Residents under lockdown must stay in their homes, except for recognized, essential work. Where the government failed in its public health response and overreached into egregious human rights violations, people began to protest. On November 24, 2022, at least 10 people died from a fire in an Urumqi apartment building. Throughout Urumqi’s province of Xinjiang and across China, citizens protested the extreme and indefinite local enforcement of Zero-COVID measures, and especially the government’s silence and the lack of public accountability.

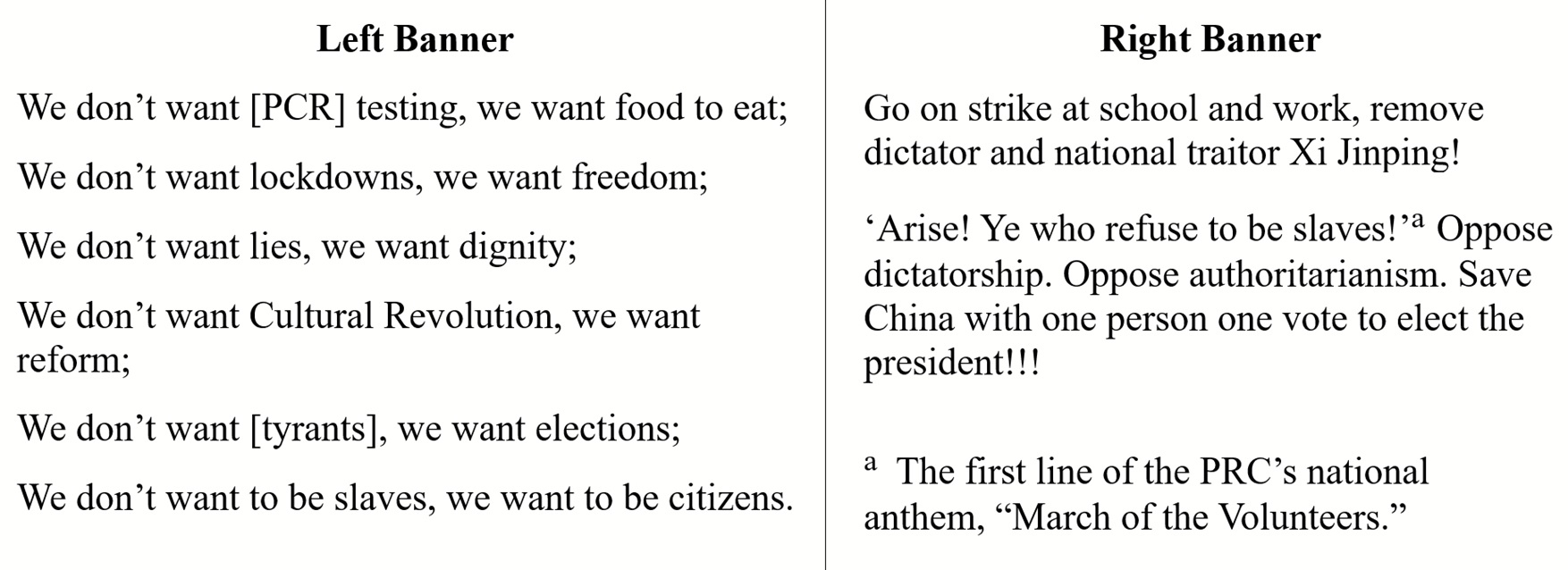

Days before the CCP’s official 100th anniversary ceremonies began, protestors on the Sitong Bridge in Beijing unfurled banners reading:

The intent behind the bridge action is not immediately obvious, and the language employed might suggest different meanings in different contexts. Is the opposition to PCR testing and lockdowns absolute (demanding no COVID restrictions at all), or relative (opposing only the coercive government overreach of Zero-COVID enforcement)? What does the commitment to “reform” mean for the continued existence of a one-party state? Is the target of protest Xi Jinping alone, or does opposition to Xi Jinping imply opposition to the Party that appointed him?

I have seen no evidence that implies COVID denial was a significant factor driving any of these protests. Regarding the other questions, I cannot provide answers, but for an important reason: what can be known and demonstrated about public opinion in China depends upon the freedom of speech of the Chinese public, and what the public believes depends upon freedom of information.

The Sitong Bridge protest quickly spiked interest on China’s Weibo social media app (discussion which was then quickly censored), but some other protest actions chose to communicate without words. “White Paper protests” appeared across the PRC, from Shanghai in the east to Urumqi in the northwest. In Urumqi, in Beijing, in Shanghai, in other protests within China, and in solidarity protests abroad, a contingent of protestors made themselves known by holding up blank sheets of white paper. The symbolic meaning behind the blank paper is demonstrated in its context: a social and political context in which holding up a white sheet of paper becomes a defiant act of protest. Whatever words the protestors write will be censored anyway, and that seems to be their point. However, not much else can be inferred about the White Paper protestors, including their number and economic demographics.

The COVID Policies Spur Workers’ Strikes and Protests

Zero-COVID policies adversely affected the daily lives of its subjects as citizens who had been systemically deprived of political rights, but these policies also affected Chinese workers in their position as workers. They engaged in strikes and protests. At the iPhone-manufacturing plant in Zhengzhou, Foxconn workers protested delays in the bonus pay they had been promised as well as COVID outbreaks, food shortages, and strict quarantine procedures that forced workers into packed living quarters on the factory campus without permission to leave. By separating workers from the general population, Foxconn put all of these workers at constant risk of transmission should any one of their hundreds of thousands of co-workers contract COVID.

Dunayevskaya wrote, “the pivot of [both private and state-capitalism] is the law of value, that is, paying the worker the minimum it takes to reproduce himself and extracting from him the maximum unpaid hours of labor it takes to keep ‘production for the sake of production’ going at the world’s most technologically and nuclearly armed level.”[13] The Foxconn workers protested for their health, they protested for the pay they had earned, and, in so doing, they challenged the capitalist imperative of production for production’s sake. They stood against riot police and Pinkertons in hazmat suits who, like the “People’s Liberation Army” under Mao, “encircled the cities and told the urban working class to remain at their production posts.”[14] Though Xi’s economic rhetoric does not signal a turn toward pre-reform Maoism, economic policy in the PRC has always been governed by the logic of capitalist production, in other words: by the national economy’s insatiable demand for unpaid labor.

The CCP’s attempts to manage capitalism can neither deliver rapid growth of industry and production indefinitely, nor provide immunity to a potential legitimacy crisis created by its authoritarianism. An economy based on capitalist production relations leads itself sooner or later into crisis, no matter whether the means of production are owned by private, bourgeois capitalists or a “People’s Republic.”

The future of the CCP depends upon its ability to enforce its authority over Chinese society, and it faces a lot of resistance from its supposed subjects: the people of China as well as peoples struggling for independence from China (in so-called Xinjiang, in Taiwan, in Tibet, in Hong Kong, in so-called Inner Mongolia, and elsewhere). The Party’s capacity or incapacity for internal reform will never tolerate the political emancipation of the billions under its dictatorship. For that reason, the uneasy compromises reached between Party policy and mass protest show how demands for democratic rights, like rights to information, association, speech, and democratic elections, are opposition to more than individual policies like Zero-COVID. They oppose the rationalized cruelty of party dictatorship.

Shanghai police stationed to prevent gatherings after clearing candlelight vigils on Shanghai’s “Urumqi” Road, when urban citizens under lockdown demonstrated in solidarity with the Urumqi fire victims. Credit: Anonymous Wikimedia uploader, uploaded on November 27, 2022.

What Next?

As of summer 2023, though the Zero-COVID Policy has been officially abandoned and public health enforcement measures have relaxed in China, Xi Jinping continues to head the same one-party state, and there is no challenge powerful enough to change this in the immediate future. Considering the difficulty in accessing thorough and reliable information about public opinion in China, it cannot be said that the diverse protests movements have succeeded or failed in their aims. But we can say that the forces of resistance embodied in these protests cannot be extinguished through political repression and coercion like usual.

Protestors still struggle for the right to remember the 1989 Tiananmen Protests. Protestors still struggle to speak about the ongoing violence the PRC commits against them, their family, their neighbors, because of their Uyghur nationality. Hong Kong still struggles to maintain some autonomy.

By suppressing these protests for human rights and dignity, the CCP provokes further resistance to its rule. Mao could not resolve the “contradictions” between masses and Party in China, and mass protests during the Zero-COVID Policy last year signal to the world that these contradictions cannot be reformed away by the Party dictatorship. Only the masses subjected to the official totalitarianism of the PRC can overcome one-party rule and carry out a revolution for liberatory politics in China.

Possibilities for the revolutionary self-organization of China’s working class, or for democratic self-determination of the masses, or for human rights protections for minority groups and nationalities reflect human tensions relatable in some degree to any nation facing internal struggle between classes under capitalism, between authoritarianism and universal rights and freedoms, between police coercion and democratic activity. Liberation from the totalitarian rule of the CCP depends upon the conscious activity of the masses over whose lives it claims sovereignty. Liberation from the inhuman rule of capitalism in all its forms ultimately depends upon the conscious activity of workers in China and everywhere else in the world.

As Dunayevskaya said of the “age of state capitalism,” “While the basic problem, everywhere in the world now, is labor productivity–how to get workers to work more–nowhere is it more urgent than in a totalitarian State. That is why it is totalitarian.”[15] Mao is long dead, yet that fact didn’t stop his “reformist” successor, Deng Xiaoping, from violently crushing the spontaneous mass uprising in Tiananmen Square, where Mao declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China and where his most famous portrait still looms. The PRC has outlasted the USSR in the endurance of a one-party state, but totalitarianism can only persist through employing deception and coercion, through exploitation and subjugation. These conditions lead to new catastrophes unless they are undermined by the masses of people resisting (state-)capitalism and creating new, liberatory alternatives.

Notes

[1] See her books on the MHI site’s Literature page and articles on the Archives page. Her first two books discuss Mao’s thought and 20th century China: Marxism and Freedom: From 1776 until Today (second and later editions, Aakar Books, 2013) and Philosophy and Revolution: From Hegel to Sartre, and from Marx to Mao (Aakar Books, 2015).

[2] Goldman and MacFarquhar (eds.), The Paradox of China’s Post-Mao Reforms (Harvard University Press, 2002), “The Changing Role of Workers”, p. 173-196.

[3] For a contemporary example, see Kevin Rudd’s recent articles in Foreign Affairs: The World According to Xi Jinping and The Return of Red China.

[4] Raya Dunayevskaya, “‘Culture,’ Science and State-Capitalism” (1971), p. 3-4. The “despotic plan of capital” confronted not only workers of “Communist” nations, but also American miners and automobile-manufacturing workers in the 1950s, who fought the despotic roll-out of automation, as described in Marxism and Freedom, p. 258 (“America is not exempt from the development of state capitalism ….”).

[5] Quoted in Raya Dunayevskaya, Marxism and Freedom, p. 321.

[6] Marxism and Freedom, p. 322-3. Dunayevskaya hyphenates the adjective state-capitalist in her usage, while the English-language translation of these CCP documents does not hyphenate.

[7] Xi Jinping’s father, Xi Zhongxun, was formerly a venerated politician and soldier, then banned from the Party and imprisoned but not killed, in these events.

[8] “China’s leaders certainly act as if they greatly fear another mass social upheaval, but many ordinary citizens remember the chaos of recent decades as well. Among average Chinese citizens, a widespread wariness of history repeating itself plays a role in maintaining the Party’s authoritarian rule.” Joanna Chiu, China Unbound: A New World Disorder (House of Anansi Press, 2021), p. 29.

“After Mao had put down the self-created turmoil called the Cultural Revolution–and after he not only ‘rehabilitated’ Deng Xiaoping, but what is a great deal worse, started to play with U.S. imperialism–there was no sort of revolutionary legacy he could possibly leave the Chinese masses.” Raya Dunayevskaya, Women’s Liberation and the Dialectics of Revolution (Wayne State University Press, 1996), p. 156.

[9] On the broader experience and legacy of the Cultural Revolution in China, see Yiching Wu, The Cultural Revolution at the Margins: Chinese Socialism in Crisis (Harvard University Press, 2014).

[10] Chuang, Social Contagion and Other Material on Microbiological Class War in China (C.H. Kerr Publishing, 2021), p. 9.

[11] Chuang: “expenditures on public goods like health care and education in China remain extremely low, while most public spending has been directed toward brick and mortar infrastructure–bridges, roads, and cheap electricity for production.” Social Contagion, p.25.

[12] The first line of the PRC’s national anthem, “March of the Volunteers.”

[13] Raya Dunayevskaya, Philosophy and Revolution: From Hegel to Sartre, and from Marx to Mao (Aakar Books, 2015), p. 263.

[14] Philosophy and Revolution, p. 165.

[15] Marxism and Freedom, p. 217.

Be the first to comment