#opportunism4Bernie

by Brendan Cooney

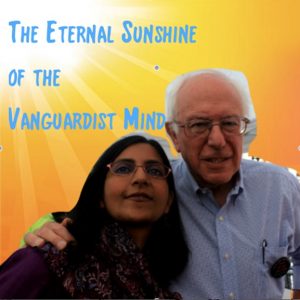

It must be great to be Kshama Sawant and the rest of the leadership of Socialist Alternative right now. After years of slogging it out in the trenches, selling papers for the revolution, attaching themselves like leeches to every popular movement that came along, they finally have proof that they have a winning strategy and that they are the party to lead the coming revolution. After all, they have Kshama Sawant, an avowed socialist, sitting on the Seattle City Council. With her help Seattle has won a $15 an hour minimum wage.

On top of all this, Socialist Alternative (SA) had another reason to be wildly optimistic and full of self-importance this election season as Bernie Sanders, a self-described socialist, came quite close to challenging Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination. All of the sudden it was socially acceptable to call yourself a socialist in mixed company, and thousands of people began to show up at Sanders rallies to hear him talk about a “rigged economy” and fighting the “billionaire class”. SA has seen this as an opening for them to push for the organization of a new mass party, one that will challenge the political dominance of the Democrats and Republicans––a party that could be influenced by a vanguard group like SA. So they have jumped into the fray with their “#movement4bernie” campaign, endorsing Sanders and actively promoting his campaign, all the while agitating for him to leave the Democrats and form a third party.

Across the pond, it is equally sunny. SA’s support for Sanders has been echoed by the Socialist Party of England and Wales, as well as by the Committee for a Workers’ International, of which both the U.S. and British parties are members.

Sanders, of course, has no intention of challenging Clinton in the general election or of leaving the Democratic Party. Sawant and the SA leadership know this. They also know that what Sanders means by “socialism” is not what their organization always means by “socialism,” though they often use the term loosely. So why are they so actively involved in the Sanders campaign? Their tactic seems to be inherited from Trotsky’s concept of the “transitional program.” Trotsky proposed that because the working class is not, by itself, revolutionary, a vanguard party cannot lead the masses by directly calling for socialist demands. Instead, vanguard parties like SA should make demands that are not actually achievable under the present system. The hope is that, in struggling for these unachievable objectives, such as Sanders running as an independent, the masses will come to see what they are up against, develop revolutionary class consciousness, and thus be ready for the vanguard party to lead them to revolution.

But the problems with SA’s #movement4bernie campaign don’t just lie in the fact that they have endorsed a Democrat. Nor are they problems unique to transitional programs. They are problems inherent in any vanguardist approach to Marxist political practice. While this essay is a critique of SA’s #movement4bernie campaign, it is also a critique of these larger problems, problems of which the #movement4bernie campaign is just the most recent, jarring example.

Vanguardists believe that revolutionary impulses will not spring from ordinary people’s experience of capitalism, but, rather, that this consciousness must be brought to the masses from the outside by intellectuals. This leads to a dishonest politics, as vanguardist groups water down their politics and their analysis in order to appeal to popular sentiments. Vanguardists also believe it is the role of Marxists to lead mass movements, since ordinary people are incapable of leading these movements on their own. Thus, rather than fostering the self-activity of workers, these groups encourage and re-enforce the capitalist division of labor, treating the mass of workers as an abstract mass of muscle to be directed. And, sadly, in their zeal for party-building, these groups compromise on theoretical principles to the point of abandoning the project of developing Marx’s critique of capital for our time. They become all about organization and not about thinking. The sad reality is that SA does not even have a coherent concept of what socialism is, let alone a coherent critique of capitalism.

This essay will outline these problems, all on full display in SA’s #movement4bernie campaign.

Voluntarism

Sawant and SA have repeatedly trumpeted Sanders’ call for a “political revolution against the billionaire class”. They repeat his call for an end to the domination of politics by “corporate America” and “the interests of Wall Street.” This all sounds good and leftist, but are socialist politics really about blaming a particular set of individuals who happen to be in the 1% for the fact that the 1% exists? The language of SA, adopted from the Sanders campaign and the Occupy movement, smacks of voluntarism.

Voluntarism is the belief in the power of free will and human action to transcend material conditions. It leads to analyses of society which privilege human actions and interests over the economic structure of society, so that, for example, the inequality inherent in capitalist society is explained by the capitalist class’s control of political and economic institutions rather than by the fact that capitalism is a mode of production based on the extraction of surplus-value from wage-laborers. Voluntarism suggests that the politicians who run the capitalist state act in the interests of capital because they ideologically identify with the capitalist class and because they are bought and controlled by factions of the capitalist class. This in turn suggests that a socialist party that was able to break free of the influence of “big money in politics” would act in the interests of the working class if it were to take control of the state.

Voluntarism goes hand in hand with an instrumentalist concept of institutions, in which institutions are seen as neutral instruments of those who run them. Instrumentalists explain the inherent problems in capitalist institutions, be it the government or the Democratic Party or businesses, by pointing to the ideological interests and the corruption of those in charge.

This voluntarist, instrumentalist understanding of society leads to a politics which believes that political and economic institutions will have a fundamentally different character if they are run by the working class. In other words, we can just swap out one set of people for another set of people and the institution, as a neutral instrument, will function differently. Hence, the call for an “independent” political party that will take control of the state and run these institutions in the interest of workers rather than capital. This is why SA’s concept of socialism just involves workers collectively running capitalist institutions. Their analysis doesn’t see a mode of production. It just seems to be a matter of special-interest groups running neutral institutions.

Marx, however, has a completely different conception of state, economic and political institutions. These aspects of the superstructure derive their core features, not from the subjectivities of the people at their head, but from the economic structure of the capitalist mode of production. This mode of production sets the goals, parameters, rewards, and punishments that determine the range of choices that people encounter when they find themselves “in control” of these institutions. From the perspective of capital, these people are embodiments of economic categories. Should they cease to do a good job in this capacity, they will be replaced with others who better embody the logic of capital.

The voluntarist ideas of SA are not unlike other notions that dominate our thinking in a capitalist society. The notion that it is poor people’s own fault that they are poor attributes inequality to the weaknesses of individuals and social groups rather than identifying social structures which produce these results. The notion that what is wrong with politics is “corruption” substitutes the personal failures of politicians for the structural determinations of the capitalist state. The slogan “corporate greed” explains the fundamental essence of capitalist profit with a simplistic idea of the personal moral failings of CEO’s and investors. All these notions, including the notion of a “political revolution against the billionaire class,” are similar in that they treat the mode of production as a timeless, unchanging backdrop, so that only human subjectivity can explain reality.

The theoretical quagmire of such a voluntarist, instrumentalist approach is on full display in SA’s “#movement4bernie” campaign. For one, SA has uncritically adopted the populist language of the Sanders campaign with its claim to be carrying out a “political revolution against the billionaire class.” This is a slogan that Sawant repeats in every public appearance and every column she writes. While it may sound, on the surface, like a socialist-ish slogan, it is, in fact, just the opposite. It is telling that SA is calling for a political revolution against a specific group of people and not an economic revolution or a revolution of the mode of production. A political revolution replaces one group of leaders with another but does not transform society.

SA has also adopted Sanders’ vague critique of a “rigged political system.” In this critique the political system generates predictable, bourgeois outcomes because it is under the influence of special interests, greedy corporations, and the super-rich. In true instrumentalist fashion, it is the influence of these powerful groups of people that creates the political realities of the system. Marx takes the opposite view, arguing that the interests and actions of state actors are a function of the mode of production. In the Critique of the Gotha Program, he criticizes the Lassallean proposals of the program with this relevant paragraph:

The German Workers’ party—at least if it adopts the program—shows that its socialist ideas are not even skin-deep; in that, instead of treating existing society (and this holds good for any future one) as the basis of the existing state (or of the future state in the case of future society), it treats the state rather as an independent entity that possesses its own intellectual, ethical, and libertarian bases.

If Marx were alive today he would likely characterize SA’s “socialist” ideas as “not even skin-deep” as well.

Are welfare-state politics socialist politics?

At times SA seems to wholeheartedly and uncritically endorse Sanders’ view of socialism:

But there exists a huge opportunity right now to overcome the endless bad choices of American politics and, by organizing independently of the Democrats, offer a real, democratic socialist alternative on a mass scale. We say, regardless of who wins the primaries, Sanders should keep running all the way to November.[1]

At other times it has attempted to differentiate Sanders’ New-Deal, welfare-state liberalism from their calls for “fundamental social change.” For example, in an April 2016 interview in the party paper, Sawant says that Sanders’ proposals are “incredibly important” and “a key part of any socialist program today,” but then goes on to say that they are just welfare-state policies while SA wants “a fundamentally different social system.”[2]

However, SA has not seemed particularly interested in being clear about this distinction. Nor does it see any contradiction between the two. Rather, it appears to have a conception in which the benevolent state-capitalism of a welfare state is some sort of stepping stone towards socialism. Perhaps this is why they feel comfortable mucking about in electoral politics and trying to get candidates into roles in the management of the capitalist state, hoping that an “independent” party can lead the way from welfare-statism to socialism.

Sawant comfortably moves between reform and revolution in her public statements. “A key part of the answer is that almost all these other countries had some form of independent working-class party. For example the National Health Service in Britain was brought in under a Labour government after World War II.”

Curiously, Sawant seems to neglect the reality that neither the Labour government in Britain, nor any other working-class party which has involved itself in the management of the capitalist state, has been able to steer the state-apparatus free from the domination of capital. This is because managing a welfare state is not an anti-capitalist task. Rather it is a task which involves disciplining labor and ensuring the smooth functioning of capitalist social relations. Welfare states involve class-compromise and reforms designed to disempower labor. The leaders of welfare states find themselves under the same material imperatives whether they call themselves “socialist”, “liberal,” or “conservative.” If Sawant wants to bring up such historical examples, she ought to be honest with her readers and explain how such approaches have always inevitably led the working class right back into the jaws of capital. Rather than being a stepping stone to socialism, welfare-state politics are a danger to workers’ movements.

Perhaps SA does not really believe that fighting for a more robust welfare state will lead to socialism. Perhaps, instead, this is part of a secret transitional program to get the masses to fight for a welfare state that the current capitalist state is not able to deliver on, thus creating a more class-conscious movement in the process. But these tactics can have just the opposite effect. People who are invested in reformism will become disillusioned with politics when these reforms fail to fundamentally change society. They may also learn not to trust “leaders” who urge them to fight for reforms that aren’t actually in the material interests of workers.

A look at the politics of SA’s sister party, the Socialist Party of England and Wales (SPEW), gives some indication of the sort of politics one could expect from SA were they ever to have influence on a third party. Across the pond, SPEW has been orienting its politics in support of Keynesian reformist programs in an effort to align its politics with the trade-union bureaucracy. This sort of anti-worker politics has led to increasing defections from the party, most dramatically illustrated in the new “Marxist World” grouping of ex-members of the Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI).[3]

Though one wouldn’t know about it by reading the sunny party press, #movement4bernie has created a sizable debate within SA itself. As much as SA likes to talk about how a future socialist society will be truly democratic, its former members paint a different picture about the internal life of both SA and the CWI, a picture of the stifling of dissent and expulsion of those who question leadership. As one former member writes, “We have also drawn the conclusion that the internal life of the CWI was always top down, always bureaucratic centralist.”

Other former CWI members recently commented:

The tendency for the CWI leadership and Sawant/$15 NOW campaign to rely too much on the left or liberal wing of the labor hierarchy[,] or to broaden the campaign or control it from the top down[,] rather than build a broader movement[,] will ensure that the success so far will be for nought[,] as democratic debate among the membership and aggressive and independent thinkers are shut down and the movement retreats.

Vanguardism and Lying

SA might counter that their support of the Sanders campaign is more cynical than many of their public statements admit:

Finding our way towards a new radicalizing generation supporting Sanders while putting forward a principled position is critical to rebuilding a socialist left. Future developments will often be similarly ‘impure,” like the Sanders campaign. Socialists will need to be actively involved in the movements of working people – even if these movements or its leaders have serious limitations – while fighting for an independent socialist position.

In other words, SA can pretend to support a campaign in order to have influence in its development, all the while secretly steering it to a more socialist position. These sort of tactics, all too common today, are the contemporary form of the vanguardist perspective. Central to vanguardism is the idea that ordinary people, workers, etc. cannot develop socialist consciousness on their own. They require a party of intellectuals to steer them toward this class-consciousness.

This sort of elitist thinking takes the form of campaigns like #movement4bernie. The campaign’s website is a whole-hog endorsement of Sanders, equating him with anti-capitalist politics: “Capitalism is plunging humanity into a social and ecological catastrophe. Bernie’s campaign shows a viable fightback is possible.” Such a front group exists to draw in Sanders’ supporters, with the aim of gradually introducing them to the socialist consciousness which their weak minds are not immediately ready for.

Accompanying this is a despicable adoption of populist rhetoric that sacrifices theoretical rigor for market impact. #movement4bernie, with its fashionable hash-tag and textese, adopts with vigor all of the sloppy language of the Occupy movement: 1%, 99%, billionaire class, fighting Wall Street, corporate America, etc. But, like the socially-awkward middle schooler whose appropriation of his classmates’ slang is just a little too premeditated, SA’s sloganeering sounds about as authentic as a Dr. Pepper commercial. Me thinks the lady doth say “99%” too much.

What SA, and all other left groups who engage in such tactics, fail to see is that these sort of tactics are the very thing that turn people away from their organizations.[4] The reason people are turned off by such tactics is that people are much smarter than vanguardists give them credit for. People can recognize when they are being talked down to. We live in an age of great cynicism, where one must maintain one’s guard at all times against a barrage of marketing. People develop defense mechanisms for filtering out hype, for knowing when they are not being told the whole story. When socialists engage in socialist marketing strategies they engage those same defense mechanisms in their audience, driving people away.

Even more problematic is the fact that this vanguardist approach cannot develop the self-activity of the working class, the force which Marx saw as the only force which can overthrow capital. Self-activity is activity that the masses do themselves and that requires that they lead themselves. They cannot be led by someone else. And why would workers want to be led by elitists who lie to them, who do not tell them their true intentions, who do not have a coherent analysis of society, and who do not have a coherent vision of socialism?

Socialism

Ever-present in the party rhetoric is the ever-sunny projection of confidence. SA, like other similar groups, project confidence in their analysis, confidence in their tactics, and confidence in their goals. As has been shown above, their analysis, riddled with a voluntarist conception of institutions, is thoroughly un-Marxist. Their tactics, encouraging workers to support welfare-state-capitalism, will lead workers back into the jaws of capital. But what of their goal of “fundamental social change,” of a socialist society? Here is where the biggest problems lie for SA, because when it comes to having a coherent theory of socialism, SA can only provide a few scattered sentences of vague, contradictory statements.

Taking a look at the “What We Stand For” statement that accompanies each monthly paper, one can find a laundry list of common-place liberal causes, none of which are particularly anti-capitalist. In fact, the demands call to mind another passage in Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program:

Its political demands contain nothing beyond the old democratic litany familiar to all: universal suffrage, direct legislation, popular rights, a people’s militia, etc. They are a mere echo of the bourgeois People’s party, of the League of Peace and Freedom. They are all demands which, insofar as they are not exaggerated in fantastic presentation, have already been realized. Only the state to which they belong does not lie within the borders of the German Empire, but in Switzerland, the United States, etc. This sort of “state of the future” is a present-day state, although existing outside the “framework” of the German Empire.

While demanding free education, public works, pensions, living-wages, better labor laws, etc., are all well and good, these reforms have existed in many capitalist societies. There is nothing particularly socialist about them.

The only demand SA makes which seems actually aimed at replacing the capitalist mode of production with a different mode of production is this:

Take into public ownership the top 500 corporations and banks that dominate the U.S. economy. Run them under the democratic management of elected representatives of the workers and the broader public. Compensation to be paid on the basis of proven need to small investors, not millionaires. A democratic socialist plan for the economy based on the interests of the overwhelming majority of people and the environment. For a socialist United States and a socialist world.[5]

Nowhere in the SA literature is there any more comprehensive explanation of what is meant by this enigmatic and contradictory statement. Even in the chapter “How Could Socialism Work?” in the CWI book Socialism in the 21st Century, by Hannah Sell, there is no substantive working out of what is meant by “democratic socialist plan,” nor an explanation of how a non-capitalist economy could have investors, or what banks would be for in a non-capitalist economy.

Returning to Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program, one can read a very succinct explanation of how a communist society could break with the capitalist mode of production, immediately doing away with all of the categories of capitalist production. Marx explains that the lower-stage of communism could make labor directly social by treating an hour of work, no matter who performs it, as an hour of social labor. In this way, all working time is compensated equally, regardless of its relation to socially necessary labor time. Socially necessary labor time ceases to be the measure of value, value relations are abolished, and labor is only social in its direct and concrete form, no longer dominated by dead labor and no longer reduced to an abstraction. True to Marx’s understanding of base and superstructure, it is this transformation of the mode of production into a new mode of production that is generative of all of the other legal, political and social relations of a new society.

In contrast, SA’s concept of socialism is thoroughly voluntarist. They see socialism as merely a matter of replacing capitalists’ decision making with workers’ decision making. Such a conception does not constitute a break with capitalist production. Rather, it just changes who is in charge of carrying out the dictates of capital. Apparently, in Sawant’s socialist paradise, workers are compensated unequally, to the extent to which they produce value for small investors. Thus labor is still dominated by the need to produce surplus-value. There are banks, so there must still be money which means there is still value production and abstract labor. “Meet the new boss. Same as the old boss.”

The presence of two strands of demands, the demand for bourgeois reforms and the demand for “fundamental socialist change,” however ill-conceived, would seem to be competing visions co-existing in contradiction. However, as mentioned above, this is likely intentional. It is likely intended to be a “transitional program” in which a vanguard party agitates for demands that it will be difficult for the capitalist state to capitulate to. In the workers’ struggle for these demands, they will come to realize the inability of capitalism to give workers the things they need. This will develop the class consciousness of the workers, making them a potentially revolutionary class. The strategy flows, again, from the vanguardist assumption that workers do not, by themselves, develop anti-capitalist sentiments. Rather, the vanguard party must act as a social engineer of sorts, guiding the workers’ struggle so that they eventually come to realize the truth about capitalism, the truth that the clever intellectuals have known all along, but kept to themselves. Ironically, while such vanguard tactics attract plenty of people with a “passion for bossing” (Lenin’s characterization of some Bolshevik bureaucrats), they do not seem to attract many people interested in actually working out any ideas about how to break with the capitalist mode of production. Were SA ever to be successful in their social-engineering project, it is not clear how they would ever lead any workers’ party anywhere except back into the quagmire of state-capitalism.

It is not surprising that an organization that attracts cadre with a passion for bossing would end up being resistant to internal democratic debate. It is thus ironic that many CWI defectors with insightful critiques of the top-down, anti-democratic internal life of SA and the CWI continue to believe in the importance of the concept of the vanguard party in creating a democratic socialist alternative to capital.

With Tactics Like These Who Needs Theory?

The sad lack of attention to developing the concept of socialism, for an organization that never ceases to enthusiastically project confidence in the need for socialism, is not uncommon. Many other groups, the International Socialist Organization (ISO) for instance, share a similar disregard for the need to engage in theoretical work. Instead, these groups think that the only role for the party is to organize, to engage in the immediate task of party-building.[6]

This reflects several tendencies. For one, it reflects the general zeitgeist of the activist left, which wants to engage in immediate, direct-action, rather than sit around reading books and thinking. With epic social and environmental crisis on everyone’s minds, it is tempting to think that what is needed is immediate action, leaving no time for thinking. But what is the point of acting if your actions just replicate the same failed politics of the past? What is the point of building movements that lead workers back into the jaws of capital? What is the point of creating a “political revolution” that could just generate another state-capitalist, Stalinist society? What if, by acting before thinking, our actions cause more harm than if we had not acted?

Another tendency is the privileging of party-building over developing theory. Prioritizing the growth of cadre over the development of ideas is a tendency that has infected many left parties, and can be traced back to Lassalle’s early influence on German social democracy. In this line of thinking the success of a party is judged by the numbers of cadre, not by the theoretical strength of its ideas. Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program is a critique of this sort of politics. He saw the Gotha Program as an abomination because it sacrificed all of the theoretical advances Marx had made in order to strike a compromise with the Lassallean faction, all for the sake of increasing the size of the party. But what good is a party if it doesn’t know what it is doing? What gives a vanguard organization the right to lead anyone if it can’t even tell you where they are leading you?

Because groups like SA believe the most important thing is to increase the number of cadre, they reduce their writings and public utterances to repetitive marketing phrases, borrow the vocabulary of the groups they are trying to co-opt, and simplify the content of their literature to the lowest common denominator. The result is that any theoretical clarity gets jettisoned for a general, vague leftism mixed with all sorts of competing politics.

Sadly, such a vague mess of conflicting ideas is a good thing to Sawant:

Whether or not you agree with Bernie Sanders’ version of socialism, it is enormously significant that, for the first time in US history, a presidential candidates who calls himself a socialist has had an actual shot at winning the presidential election. And to his credit, he has not backed down from the label. He has shown that socialism is no longer the barrier that it used to be during the Cold War. In fact, his campaign has demonstrated there is incredible interest in socialism, particularly among young people. This is a sea change.

But if Sanders and SA disagree on what socialism is, and if Sanders’ supporters all have different ideas of what socialism is, then the only fact of “enormous significance” is the fact that so many competing ideas can hide behind the same word. It is not significant that a wide swath of people can project what they want to see and hear onto Sanders. The same phenomena happened with Obama’s first election campaign. Sanders’ campaign has certainly not proven that there is “incredible interest in socialism” if everyone means something different by the term. After reading SA’s literature I am not even convinced that SA is really interested in socialism.

Marx’s Humanism

Marx took a very different approach to theory. For Marx, the critique of capitalist social relations was a theoretical expression of radical impulses that already existed in the self-activity of workers in their struggle against capital. Rather than assuming that workers could not attain revolutionary consciousness on their own, Marx saw workers’ struggles as embodying, in concrete form, the theoretical ideas that needed to be worked out in revolutionary thought.

This suggests a different sort of politics than the worn-out vanguardism of 20th century Marxism. Why should Marxists specifically seek to lead mass movements? Do workers need more bosses? Instead, what movements need is critical voices to give theoretical expression to their struggles against capital, to critique bourgeois influences, to demystify the forms of appearance of capitalist social relations, to foster constructive debate, and to aid in the working out of the theoretical ideas necessary to advance class struggle. If the aim of socialism is the “all-round development of the individual,” as Marx suggests in his Critique of the Gotha Program, then a Marxist politics should begin with the premise that workers can and should lead themselves.

For those vanguardists who think otherwise, because they have so fully swallowed the dogma of the backwardness of the workers that they can never regurgitate it, it may be constructive to ask themselves where such politics have gotten us in the past, or indeed, where they even think they are leading us. If “leaders” like Sawant cannot distinguish between populist rhetoric that mystifies the essential social relations of capital and Marx’s attempt to illuminate these relations, if they cannot distinguish between the liberal reforms of a benevolent state-capitalist like Sanders and a truly revolutionary demand, if they cannot articulate the means by which a society could break with the capitalist mode of production, then they don’t deserve to be socialist leaders in the first place. But the more important thing to understand is that these failures are not a personal failing on the part of these individuals or these parties. These failings are the result of the vanguard approach to Marxist politics, an approach which privileges party-building over theory, bossing over self-development, voluntarism over Marxism, and propaganda over thinking.

Afterword/Anticipation of Response

The response of vanguardists to these critiques can be predicted. Inevitably such critiques are met with the objection, “But at least we are doing something! What are you doing other than sitting around critiquing the real Marxists who are in the trenches doing real work?” Such a response reflects how deeply ingrained are the dogmatic assumptions of vanguardism. Why should doing things be a measure of whether one’s ideas and critiques are valid? Why should number of cadre be a measure of correct tactics? Donald Trump is very popular. Are his ideas and tactics something to be emulated?

I think that if parties like SA were to think objectively about the impact of all of their “doing,” they might see the truth in many of the arguments advanced in this essay. Vanguardists like SA and the ISO are many people’s first encounter with organized socialists, and the vast majority of these people come away from these encounters with the negative impression that socialists are elitist, pushy, manipulative, not upfront about their intentions, and full of shallow, simplistic ideas.

Further, why isn’t theoretical development considered “doing something”? What a perfect example of the total break between theory and practice in the modern vanguard party! It is mind-blowing that SA leaders, who have spent years in the party, still churn out an endless cascade of mind-numbingly simplistic articles month after month, preaching to the lowest common denominator, reciting the same tired, wrong ideas year after year. If they aren’t interested in developing their ideas, they ought to just invest in a computer program to write those articles for them. How can they claim to have some privileged access to revolutionary consciousness while at the same time showing no interest at all for putting work into revolutionary thinking?

[1] Editors, “Defeat the Corporate Establishment. Sanders’ Campaign Faces Key Test.” Socialist Alternative, issue #21, March 2016.

[2] “Interview with Kshama Sawant. What is Democratic Socialism? Bernie Sanders Popularizes Socialism to Millions.” Socialist Alternative, issue #22, April 2016.

[3] See, for example, this representative statement by a recent defector.

[4] See, for example, how some Sandernistas have responded to SA’s tactics.

[5] This, and the rest of their demands, are printed in the first page of every Socialist Alternative newspaper.

[6] There has been much debate about SA’s decision to endorse Sanders, including an ongoing debate between SA and the ISO. However, the debate is completely on the plane of tactics. The ISO thinks it is foolish to endorse a Democrat, stressing that the importance of building an independent party, while SA thinks they can use the Sanders phenomena to build interest in a new independent party. Aside from this tactical distinction there is little theoretical difference between the two parties. Both share the common problems of voluntarism, instrumentalism, vanguardism and the sacrifice of theoretical ideas for party-building.

I would like to thank Brendan Cooney for this fundamental, comprehensive, and synthetic Marxist-Humanist critique of SA.

Here are my three favorite paragraphs.

(1) “Returning to Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program, one can read a very succinct explanation of how a communist society could break with the capitalist mode of production, immediately doing away with all of the categories of capitalist production. Marx explains that the lower-stage of communism could make labor directly social by treating an hour of work, no matter who performs it, as an hour of social labor. In this way, all working time is compensated equally, regardless of its relation to socially necessary labor time. Socially necessary labor time ceases to be the measure of value, value relations are abolished, and labor is only social in its direct and concrete form, no longer dominated by dead labor and no longer reduced to an abstraction. True to Marx’s understanding of base and superstructure, it is this transformation of the mode of production into a new mode of production that is generative of all of the other legal, political and social relations of a new society.”

(2) “[The disregard for the need to engage in theoretical work] reflects several tendencies. For one, it reflects the general zeitgeist of the activist left, which wants to engage in immediate, direct-action, rather than sit around reading books and thinking. With epic social and environmental crisis on everyone’s minds, it is tempting to think that what is needed is immediate action, leaving no time for thinking. But what is the point of acting if your actions just replicate the same failed politics of the past? What is the point of building movements that lead workers back into the jaws of capital? What is the point of creating a “political revolution” that could just generate another state-capitalist, Stalinist society? What if, by acting before thinking, our actions cause more harm than if we had not acted?”

(3) “Further, why isn’t theoretical development considered “doing something”? What a perfect example of the total break between theory and practice in the modern vanguard party! It is mind-blowing that SA leaders, who have spent years in the party, still churn out an endless cascade of mind-numbingly simplistic articles month after month, preaching to the lowest common denominator, reciting the same tired, wrong ideas year after year. If they aren’t interested in developing their ideas, they ought to just invest in a computer program to write those articles for them. How can they claim to have some privileged access to revolutionary consciousness while at the same time showing no interest at all for putting work into revolutionary thinking?”

RD: The last dogma: “the backwardness of the masses.”

Tom

Merely a pedantic editorial comment, but would you mind correcting the following sentence? “The reason people are turned off by such tactics is that people are much smarter then vanguardists give them credit for.”

Ismay: the typo is corrected. Thank you for pointing it out. We strive to publish articles with correct grammar, punctuation, etc.–we allow them to be in either US or UK style–because we respect our readers and want our ideas to be as accessible to them as possible.